=========

V Drops of Water,

Caves, and

Blood

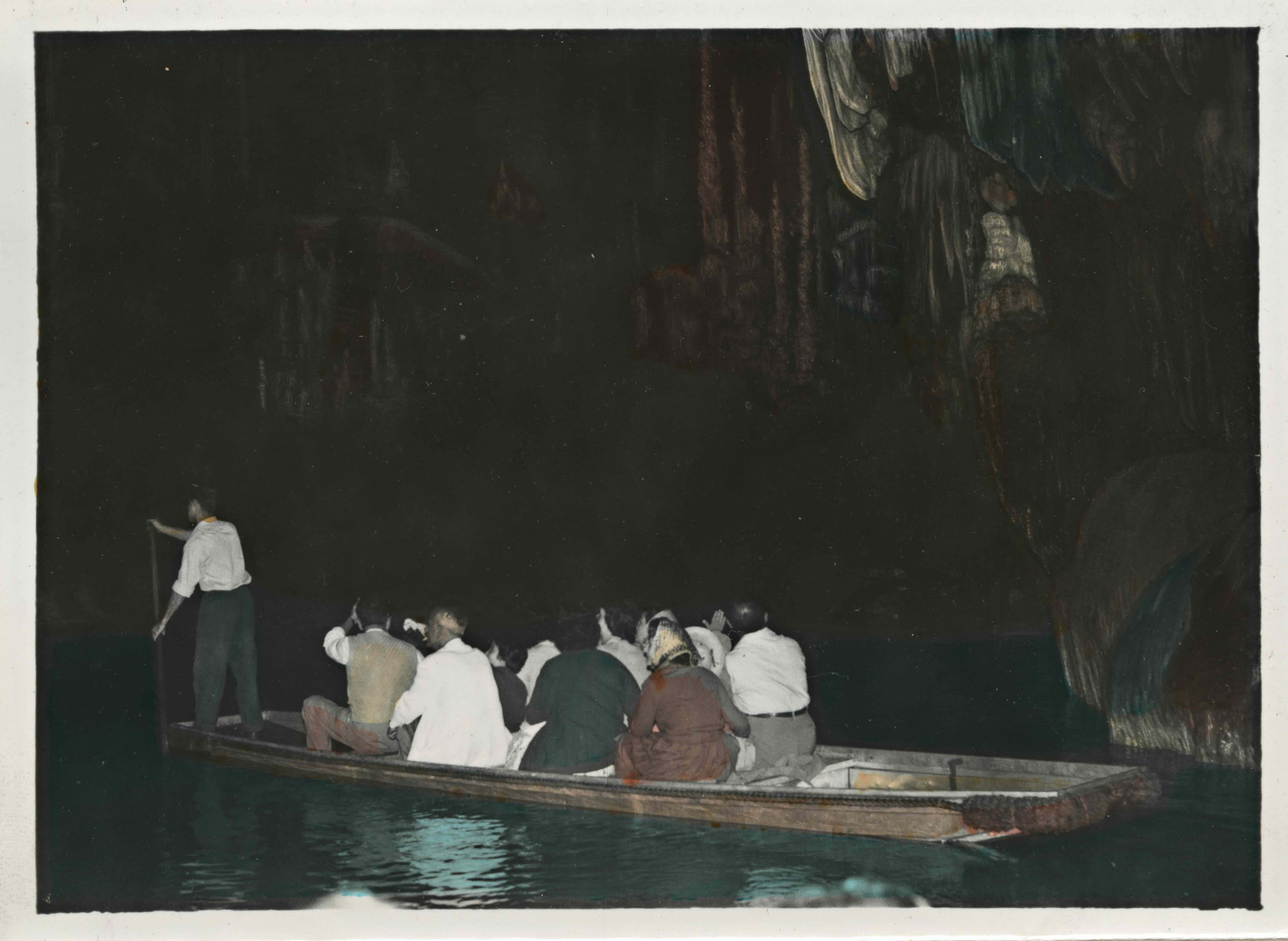

In this piece I have argued that these postcards show a direction, both real and imagined. Collectively, they illustrate a paradigmatic set of signs which form an ensemble in how the tourism industry developed, both visually and conceptually.

One location would call to mind the other as they rested onto/into the time and view of the prior flipbooks of place. The reader may have noticed that in one flipbook the other flipbooks are often seen. While born from photography, these postcards present a “cinematic dissolve,” a skipping of a stone across water...from one image to the next.

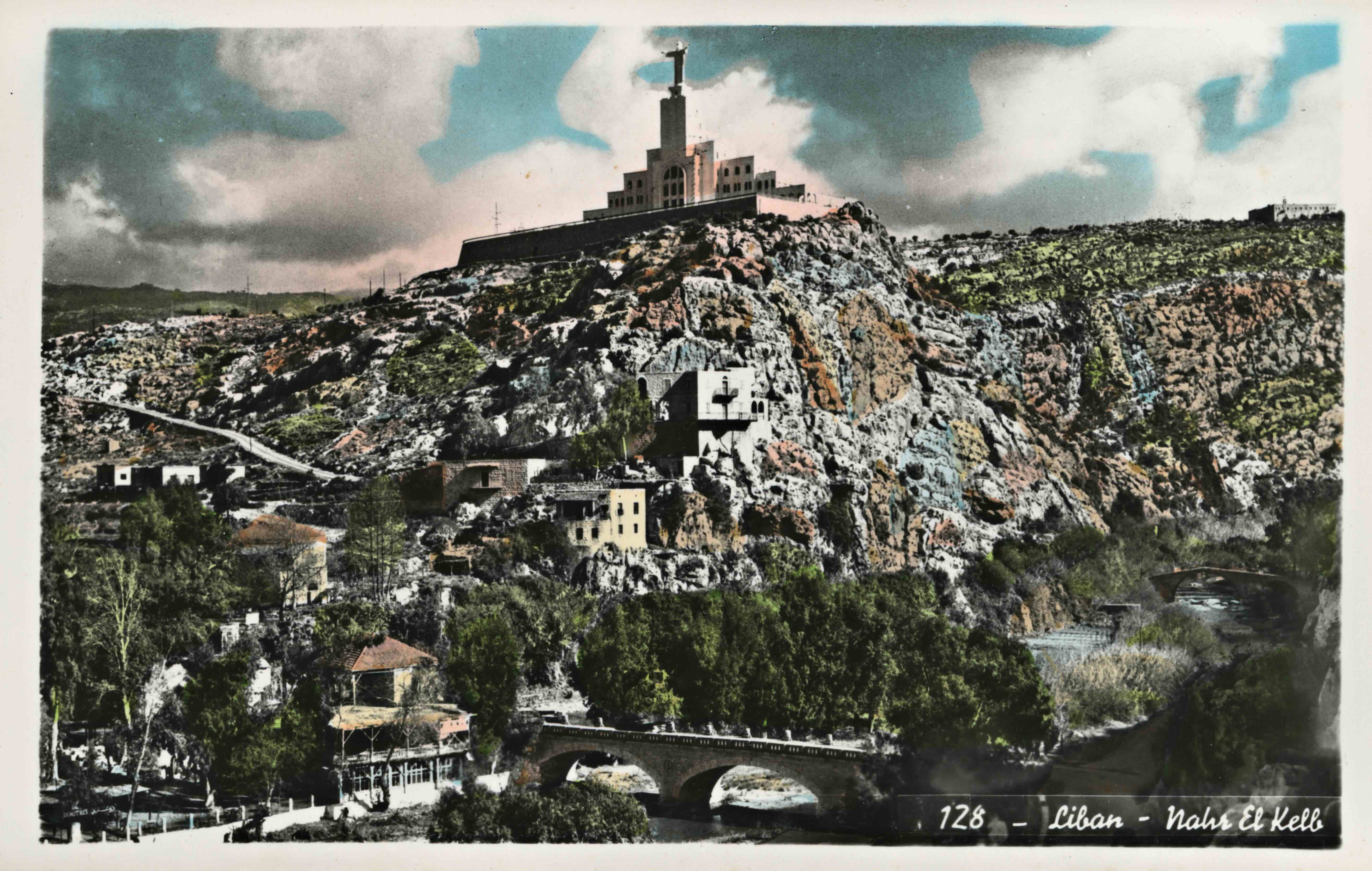

Given the relationship between these locations in close proximity, is it not surprising that Dog River is our departure point and our return. This sedimentary layering of postcards, a serial scripting of surfaces, comes to illustrates a directionality of mobility and tourism as it became realized on 7KM of land north of Beirut. This piece is not a history of these three sites, of postcards in Lebanon, nor does it posit traditional “academic” conclusions.

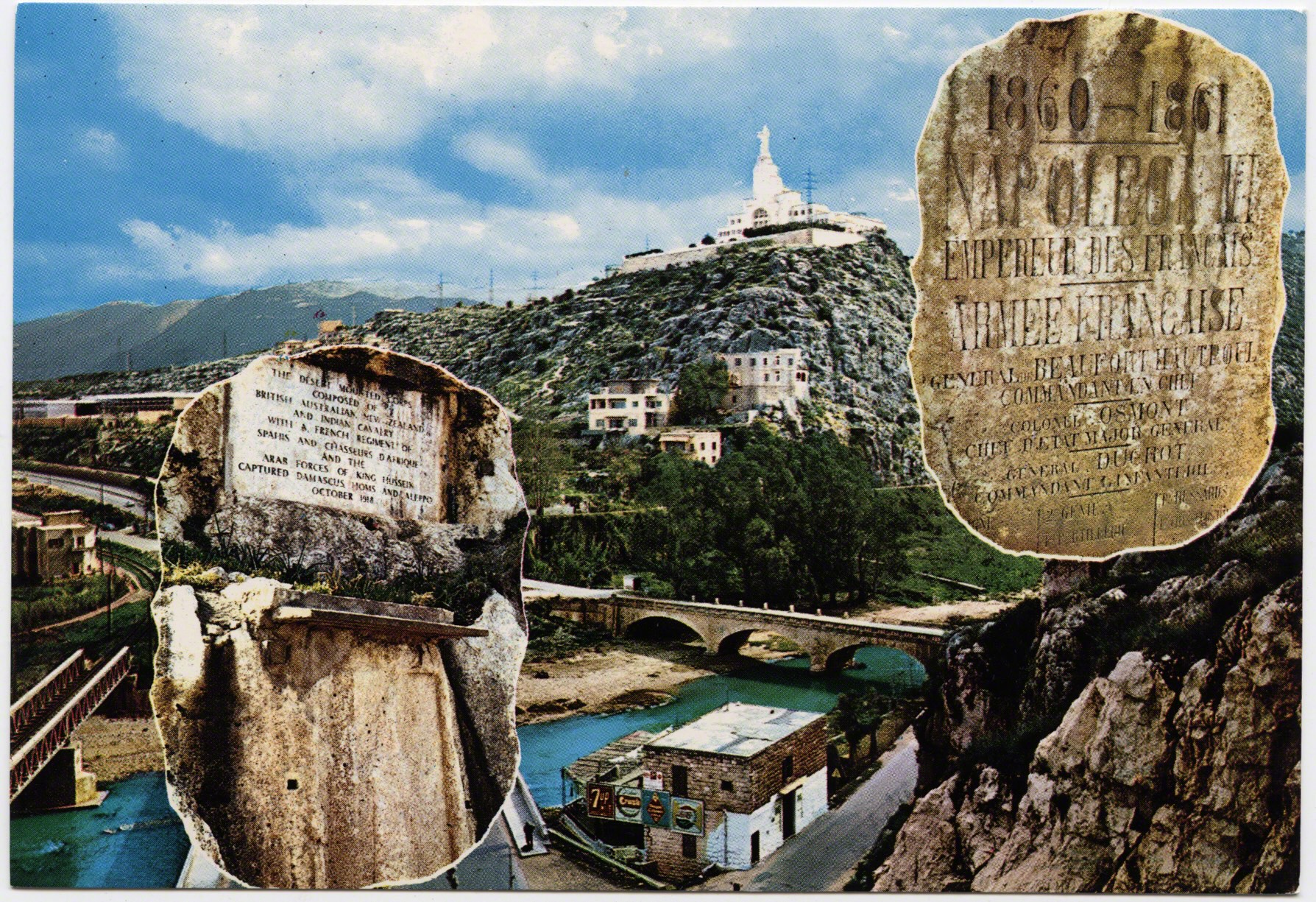

We started with a rock face as a bridge in time. The stele there illustrate seals of men as they crossed Lebanon, just as the postcards index a movement of bodies and desires that hoped to represent Lebanon in their own epochs. In sum, these postcards go from images of conquest to casinos, in which risk of life becomes just a game of chance; the Virgin Mary transforms into bikini-clad women; the bridge into an aerial tram; a landscape divided by a meandering river becomes evenly quartered and cut into bungalows and beaches where in effect it is too small to make out the image with clarity. But we know what is indexed.

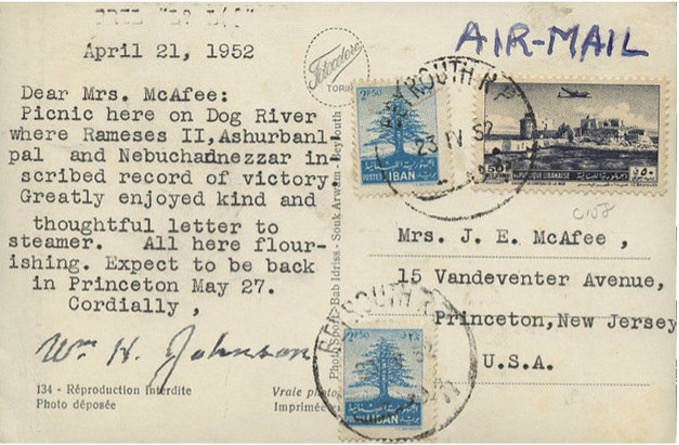

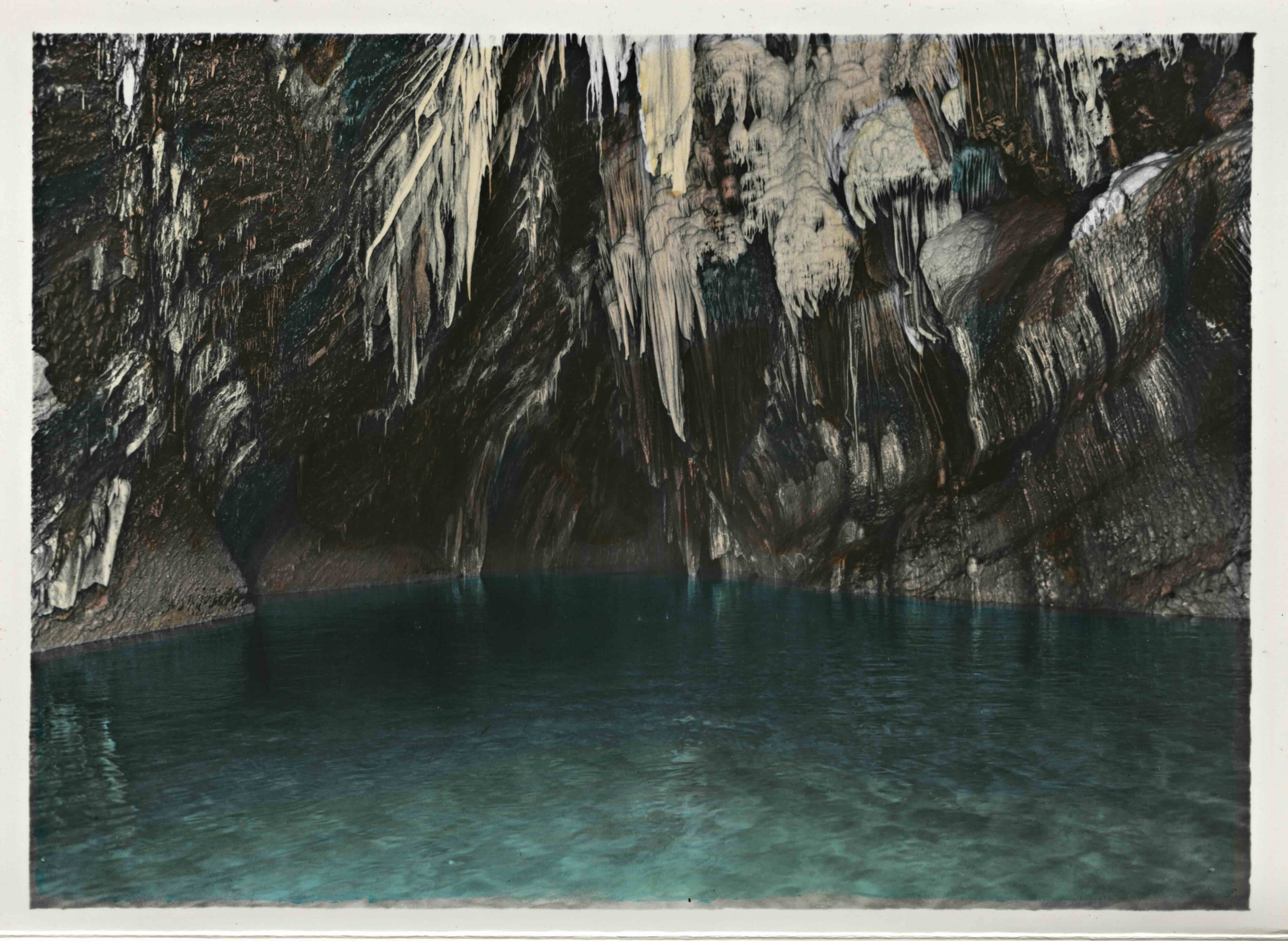

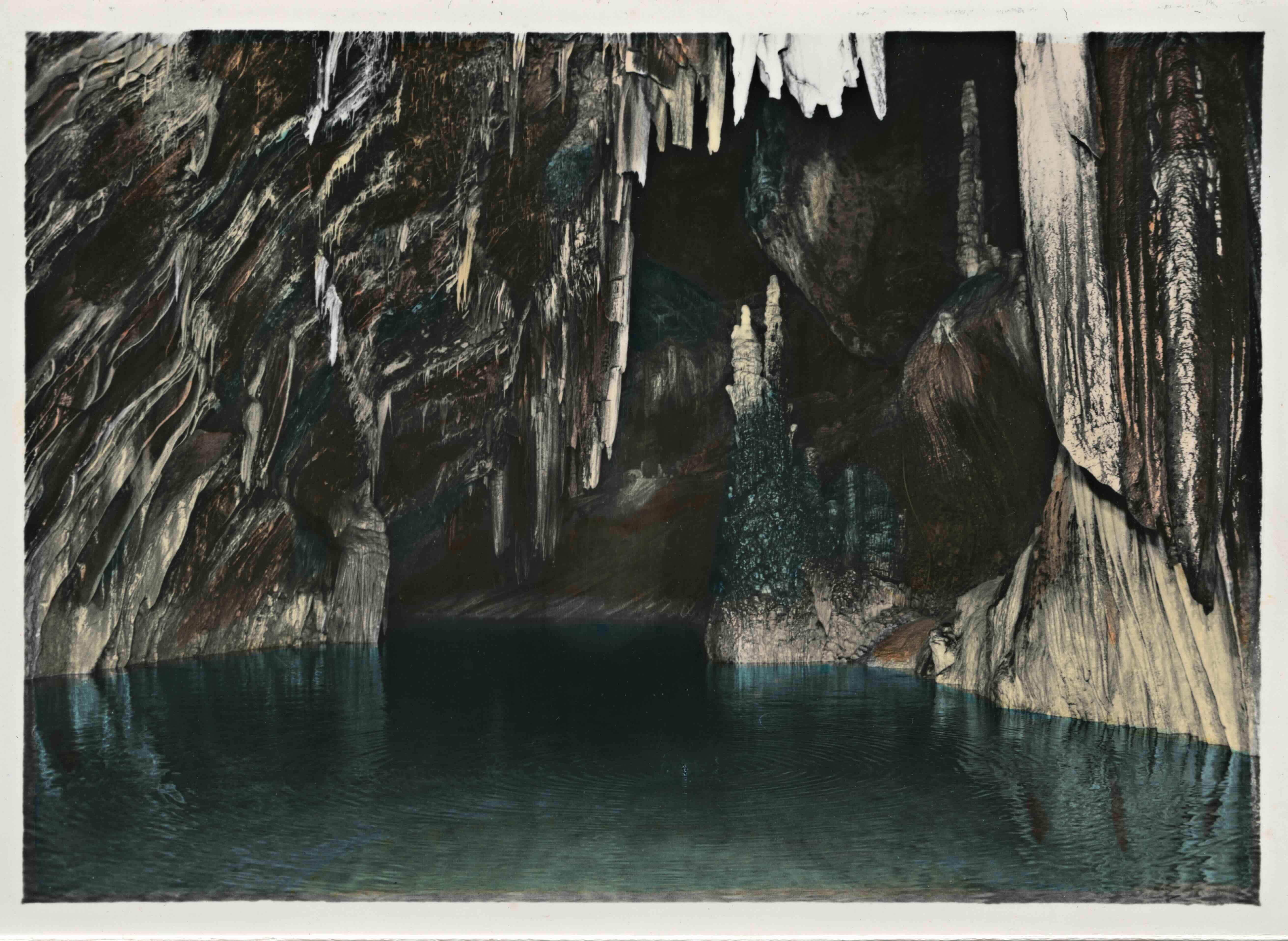

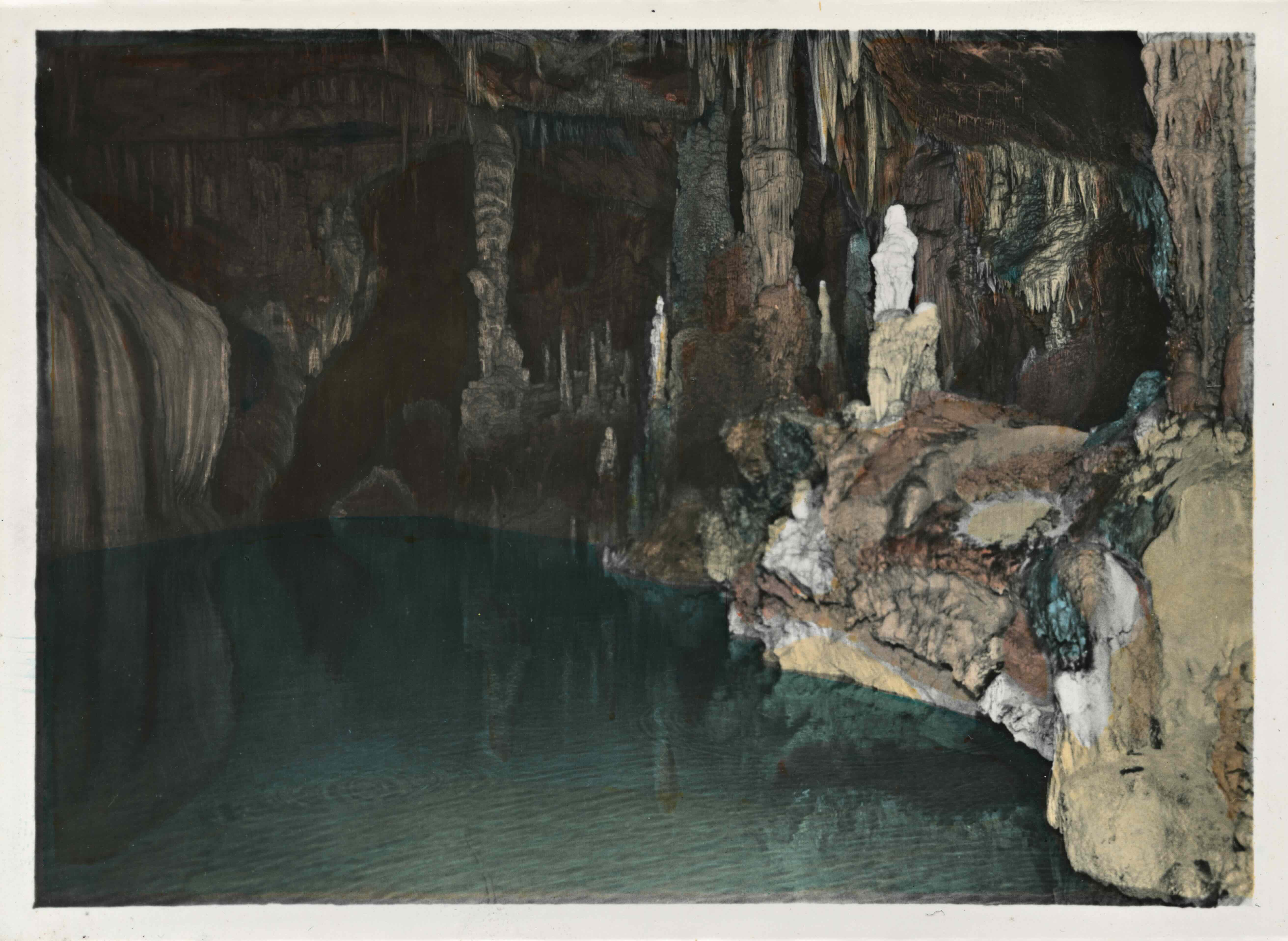

In 2011, I sat with a friend (whose grandfather had originally recounted the story of Dog River (at the start of this piece). We were at Jeita, a renowned series of caves, and the largest tourist attraction in Lebanon. There are multiple levels within the caves and it is famed to house the world’s largest stalactite. This cavern, much like how “Lady of Lebanon” is now called Harissa, the caverns used to have a different name other than the village (Jeita) where they are situation. Decades prior it was called Grottoes de Nahr al-Kalb (Dog River Caves) because it is the source of this river. The water streams out of the immense caves, forming Dog River and flowing down to sea.

As the two of us sat near a waterfall at Jeita, I mentioned Napoleon’s plaque, just a few miles down by the highway. At this point, I had never visited and I asked how best to get there. My concern was, where does one stop? You’re actually on a highway off-ramp. He reassured me that it wouldn’t be impressive, and that the inscriptions were just “old stuff” or “things from the [Lebanese] army.” As we sat waiting for our friend to come back from the bathroom and we could hear the falling water to our side, and below us a river.

His friend returned and joined our conversation talking about the level of the river. It was Spring and the water flowed with force. At one point he chimed in: “you know, once a year the river turns red, like blood.” It happens “right after Easter” he noted. As I write this might we say that blood in the river is from the dog? Or perhaps all those killed in the Lebanese Civil War? Or might the river run red with the blood of those killed by all many armies of marauding men driven by greed and ego that passed through, marking their voyages over the centuries in stone?

An Arabic magazine from 1955 noted that Dog River river isn’t important because of the “depth of its water, or the length” but because it is the “battlefield between the invaders and the residents of the area” (Al Majalis al Musawara 1955:30). It was a place of conflict, control, and movement, between foreigners and locals. As I have collected postcards of Lebanon for years I originally had little interest in Dog River. In fact, none. Yet, somehow I ended up with handfuls of cards from this location, maybe because they are so numerous (and cheap). As I considered writing something related to postcards, visual culture, and tourism I looked through stacks and stacks of cards. Some of the postcards in my collection were bought on a whim while many others were sought out with intention.

How did I settle on Dog River? I guess I fell in, swept away by the connections, myths, and views. The deeper I investigated, the wider the relationships and scope of imagery became. I am reminded of Virilio’s comparison of an archeological dig to a field of vision: “to see is to be on guard, to wait for what emerges from the background, without any name, without any particular interest: what was silent will speak, what is closed will open and will take on a voice” (1994).

Seven kilometers down from where we sat at Jeita, the wellspring of this river meets the sea next to the rock face etched by men. For millennia this water carved stone beneath the surface. The water flowed through the innards of the mountain forming paths. Think of how stalactites and stalagmites are built - drop by drop. Caverns shapped by movement, like wind beneath the surface. The river emerged to the surface and flows into the Dog River valley, which she has sculpted. Dog River passes under the Mamluk bridge, Ottoman bridge, a modern highway, and by the stone escarpment with the fading inscriptions of men’s ego to monumentalize their passages. It is the river over which travelers had to pass and also which has historically supplied the majority of Beirut’s water supply allowing it to modernize over the last century (Gunn 2007: 997).

Again, consider the postcards like drops of water in this larger meteorology of affect and atmospheres of mobility. The river makes an impression on the land, just like each traveler on the surface. The French philosopher Bachelard posits a relationship of water and imagination: “The form of water is internal and invisible, but it also combines, composes and dissolves. There is an ‘essential destiny associated [with water] that endlessly changes the substance of being’” (1983:6). Once a postcard was sent, it was released into the world. As Dog River enters the sea the particles float and flow elsewhere. They might evaporate, become tucked in a cloud, or fall on a new landscape – the energy passed on in new forms.