=========

II Surface of a River

Departing Beirut, heading north to the bay of Jounieh, one must first pass over “Dog River.” Many years ago, before I knew the significance of this location, a Lebanese friend recounted how his grandfather had explained the river’s unique name when he was a child. He was told that a protective dog guarded the mouth of the valley on the banks of the river long ago. One day a traveler passed and killed the barking dog for being territorial. The traveler continued on his way across the river. My friend then noted that to this day, once a year every spring, the river runs “red with blood,” which proved that it was the dog’s river.

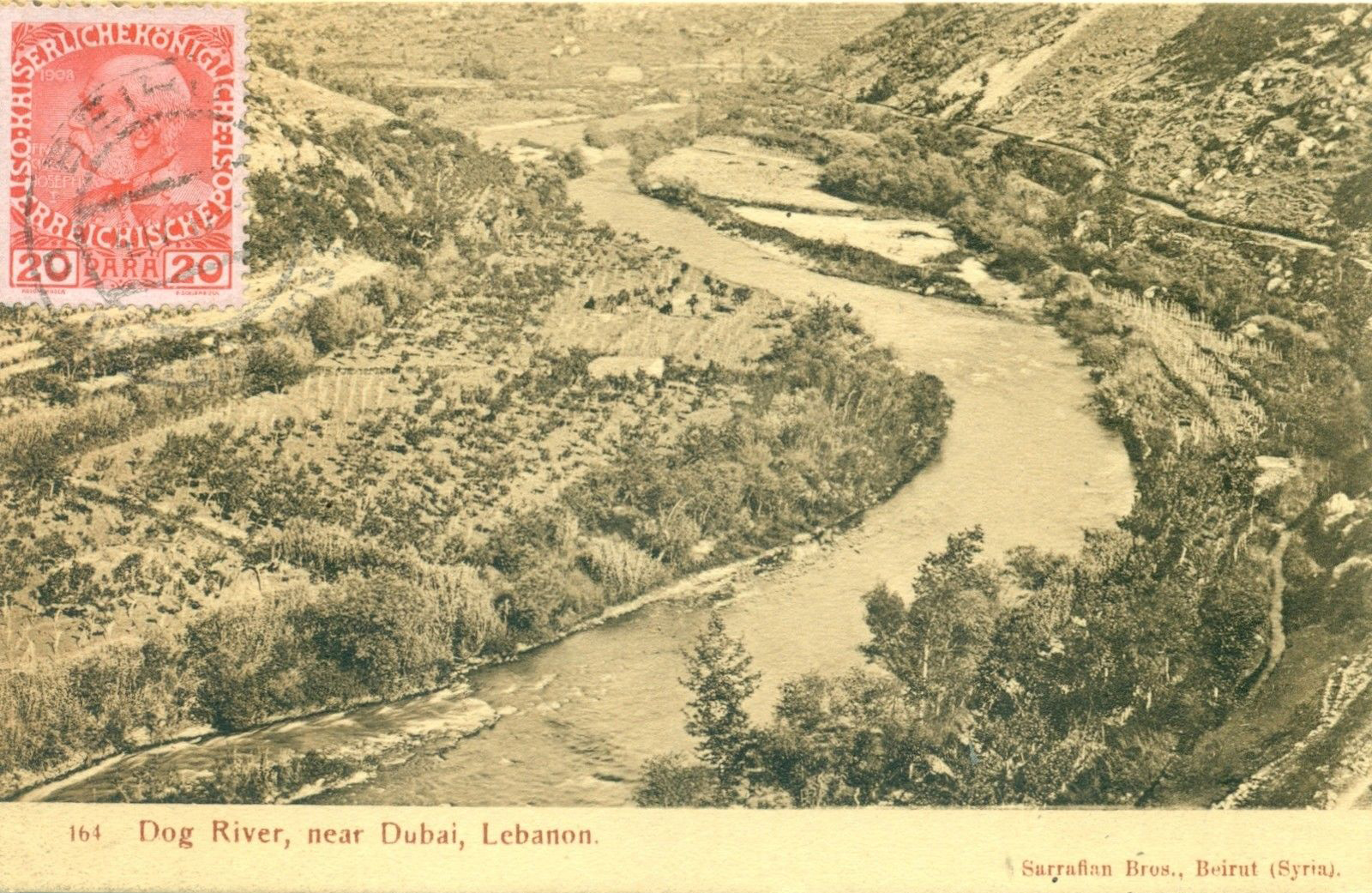

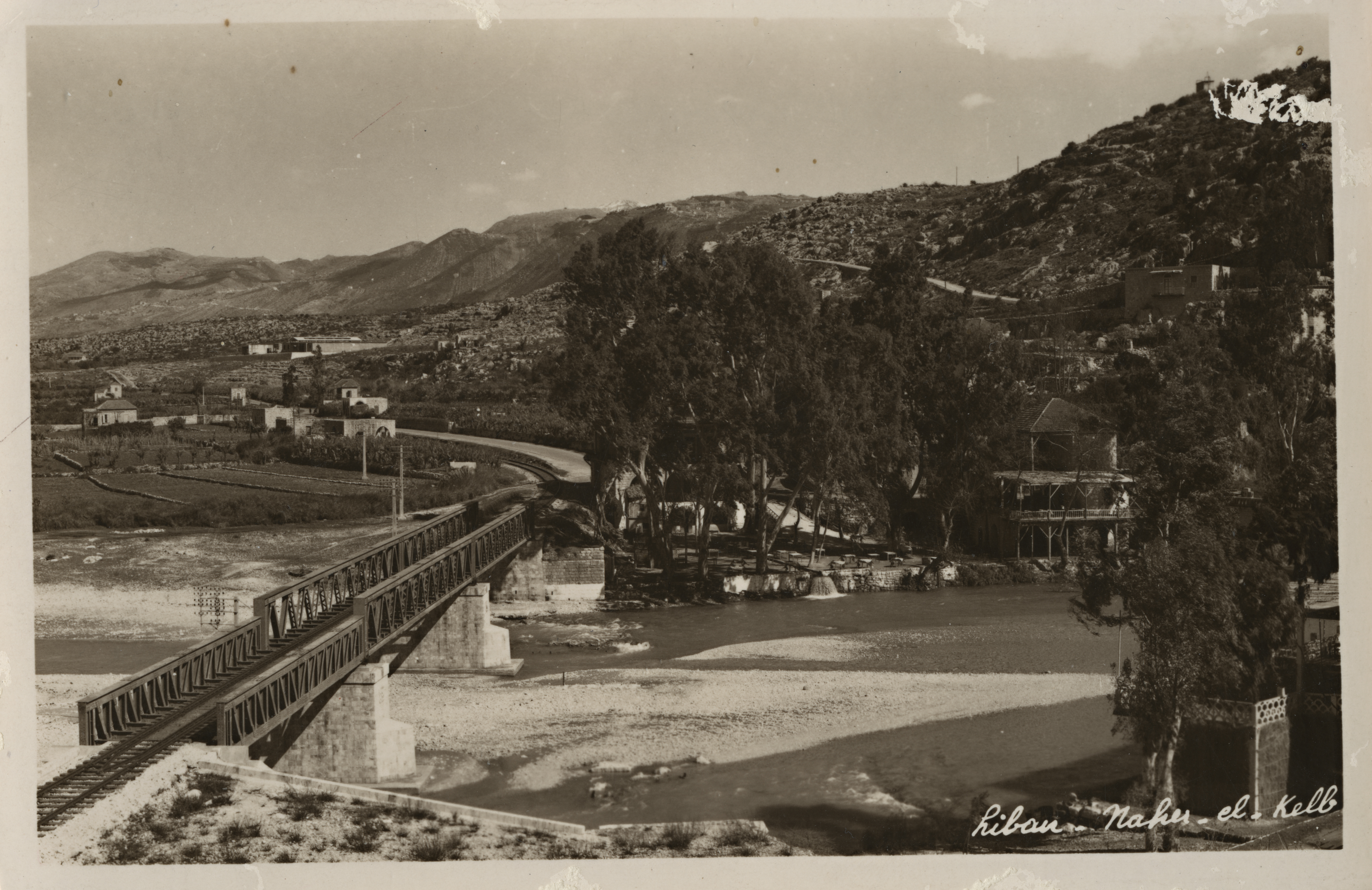

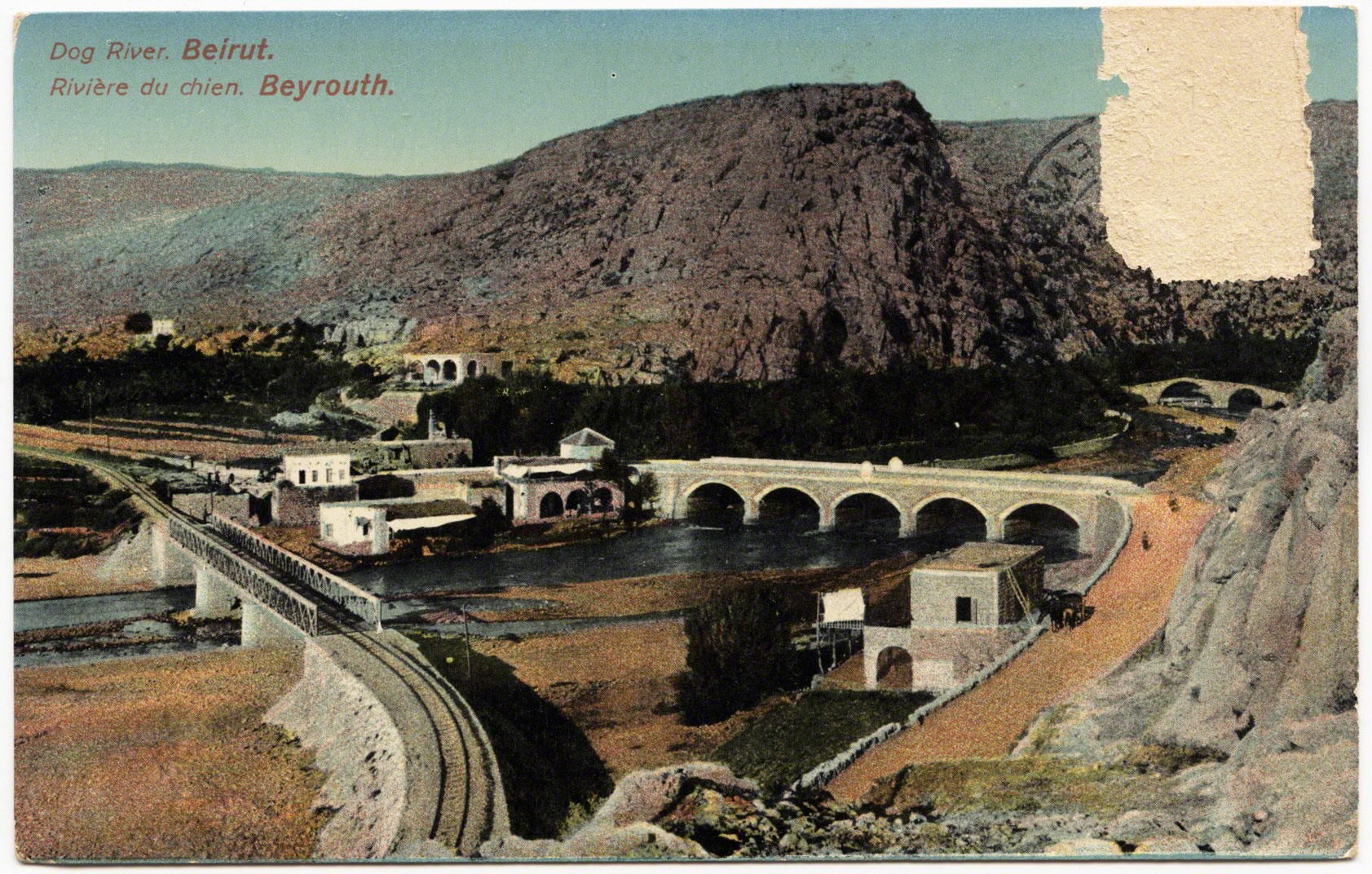

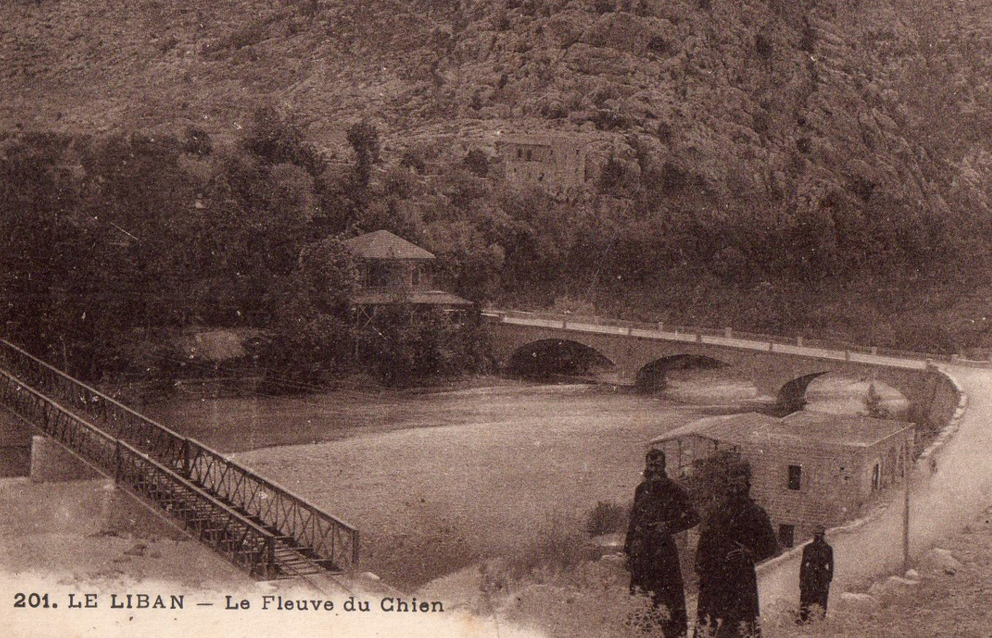

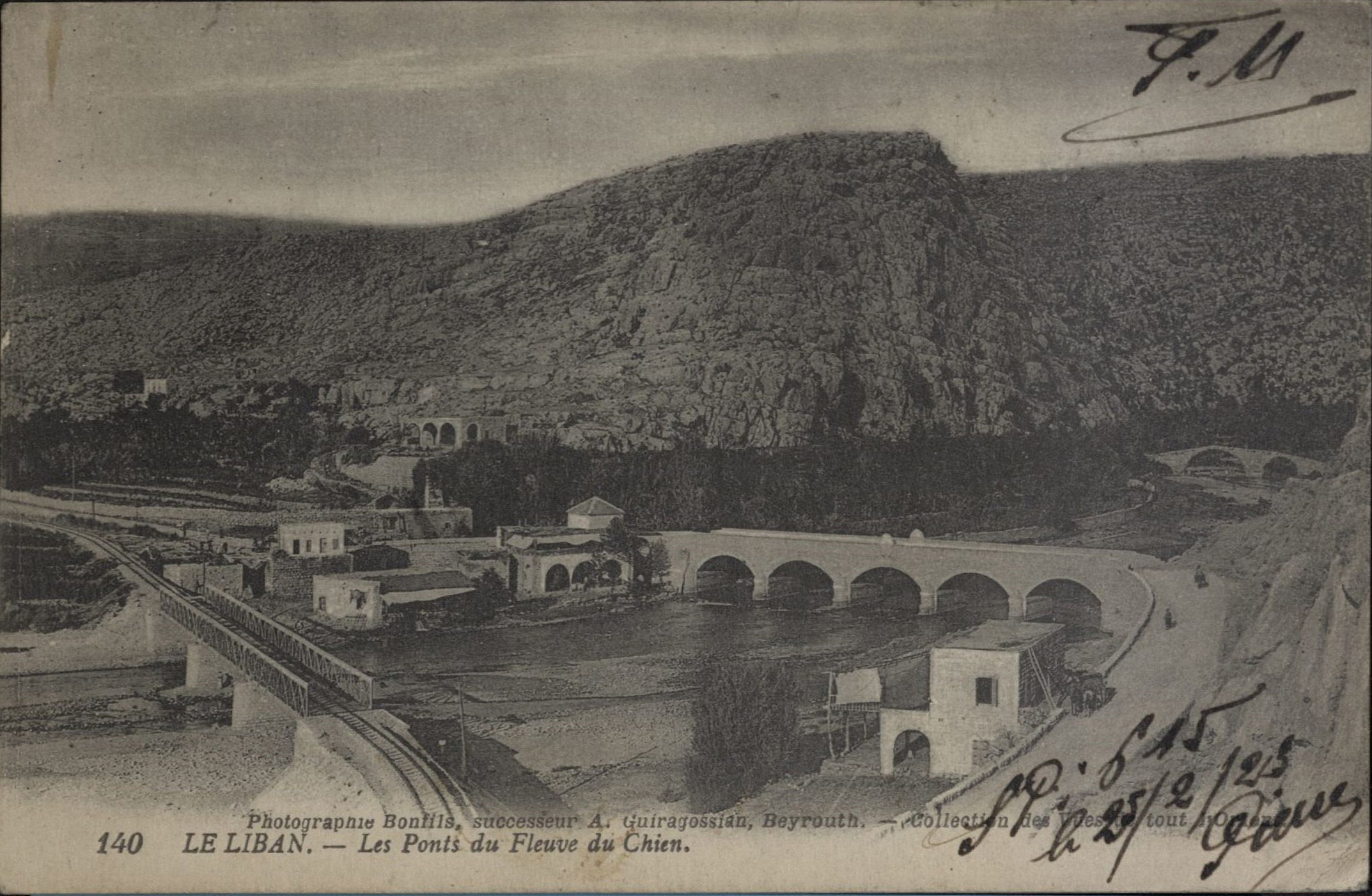

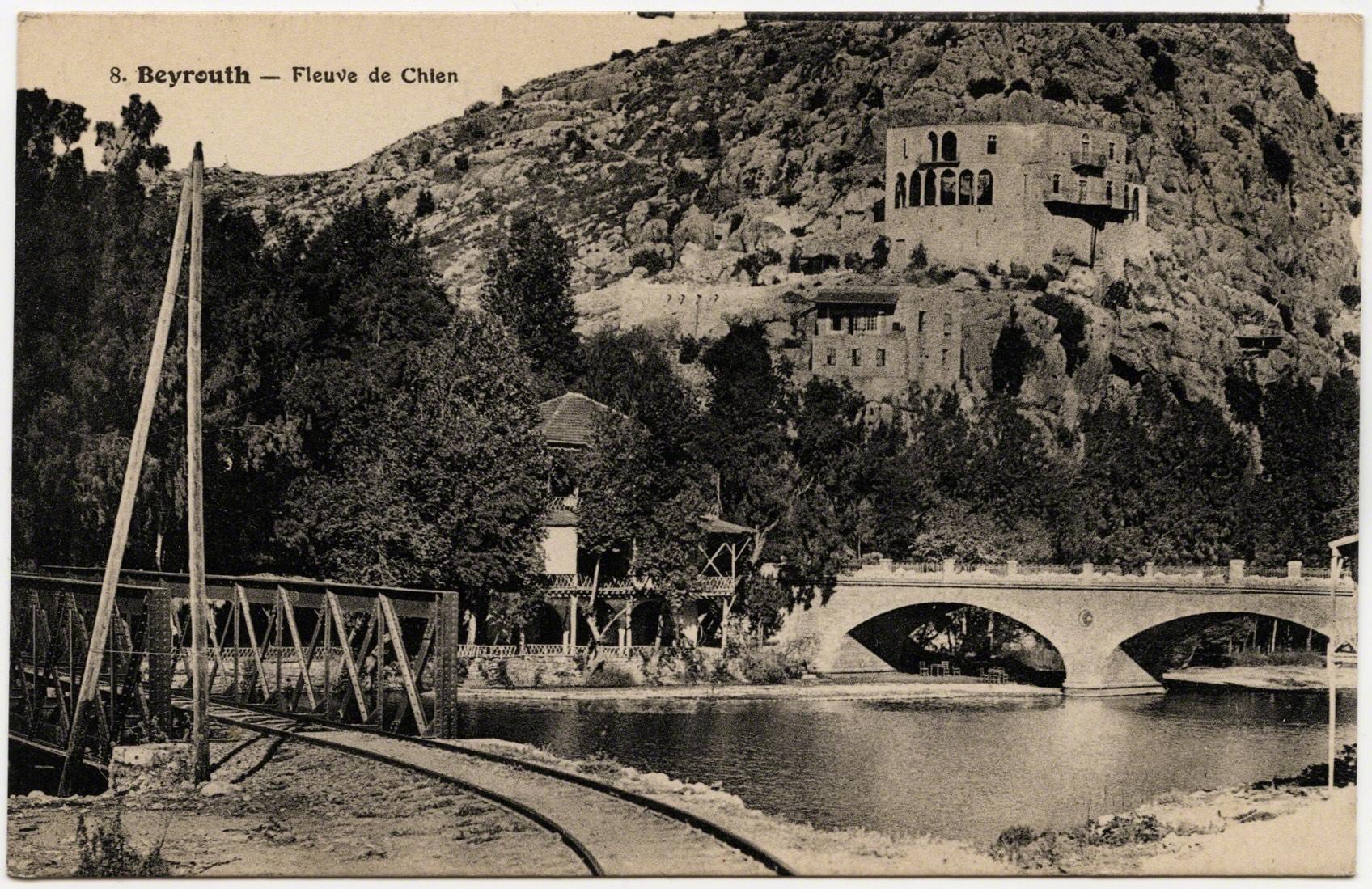

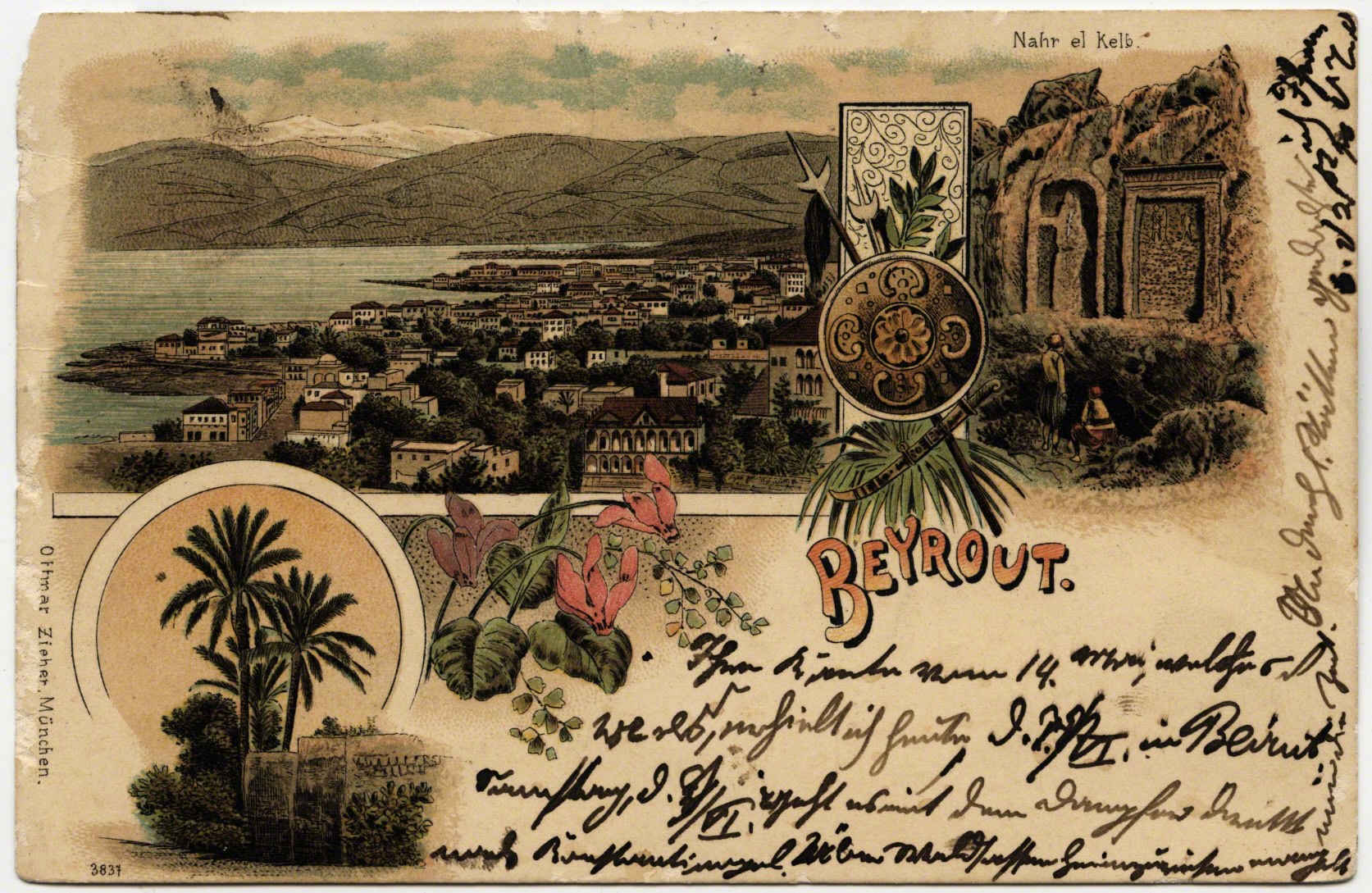

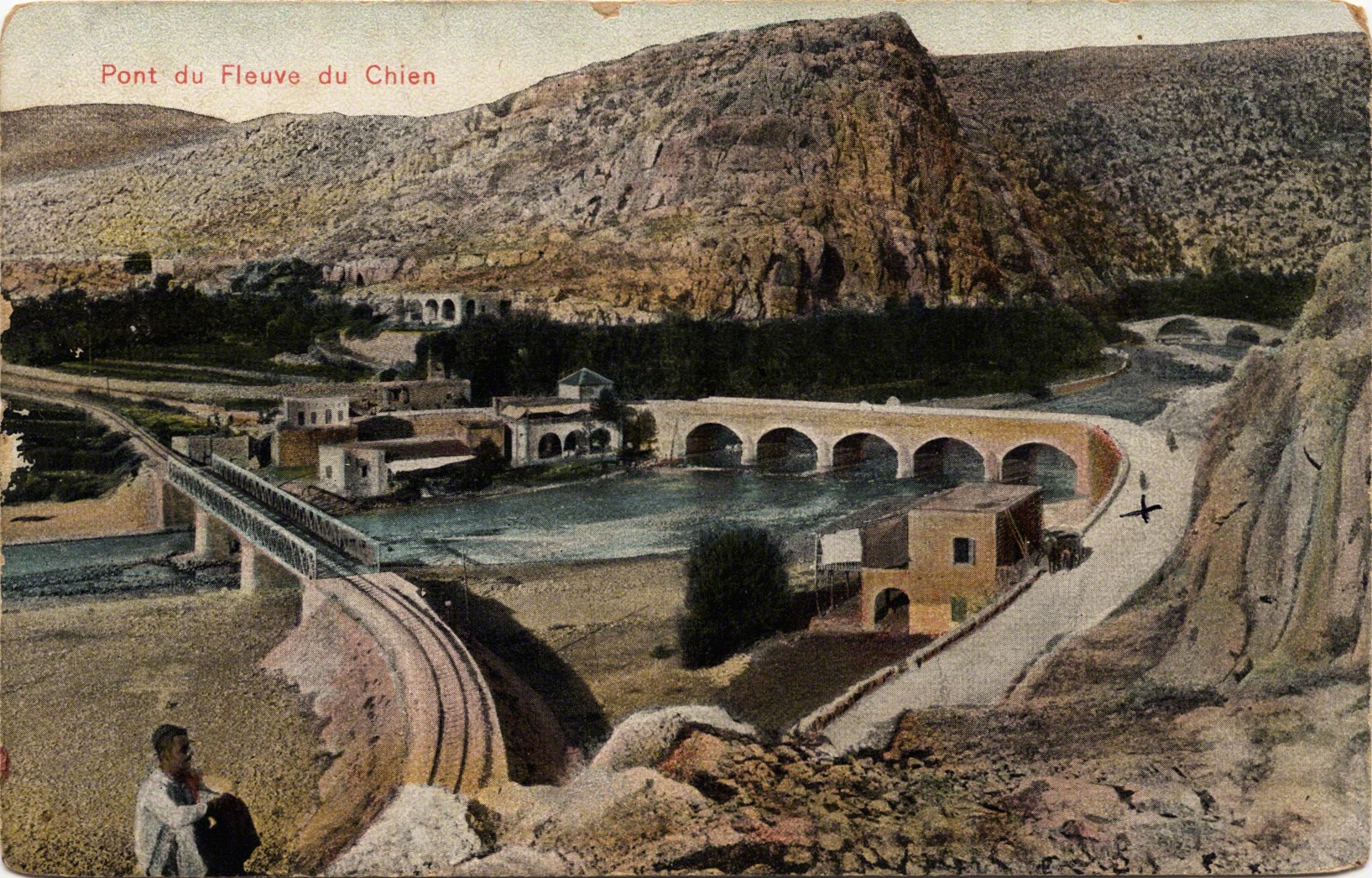

This yellow tinted postcard was mailed in 1914 and is a view looking into Dog River. The next looks out to sea and had a stamp before it was likely removed by a collector. These postcards depict quant views of a uniquely named river meeting the sea, yet the image, and the frequency of it’s appearances, signal other profound meanings.

There are many other origin stories around the name and signification of Dog River: there was a “monster of the wolf species” chained on the banks (Playfair & Murray 1890: 78); on the cliff there was a dog statue that “barked lustily” if it saw a “hostile ships” and his cries would be heard in Cyprus (Learly 1913: 34); other said there was no dog but just the wind’s howl. Or was this site nothing more than a milestone on a well-worn path where the path narrowed?

Rihani writing in Arabic cited a myth in which travelers had to answer the dog’s “puzzle;” safe passage across his river found only in a correct answer (1930: 13). If the traveler failed to solve the puzzle, “the dog swallows him without breaking a single bone!” (ibid). Rouchi also writing in Arabic noted a white rock statue of a dog overlooking the sea and the dog’s face was carved on the rock face itself, and was used to detect the invasion of armies and foreigners (1948:75).

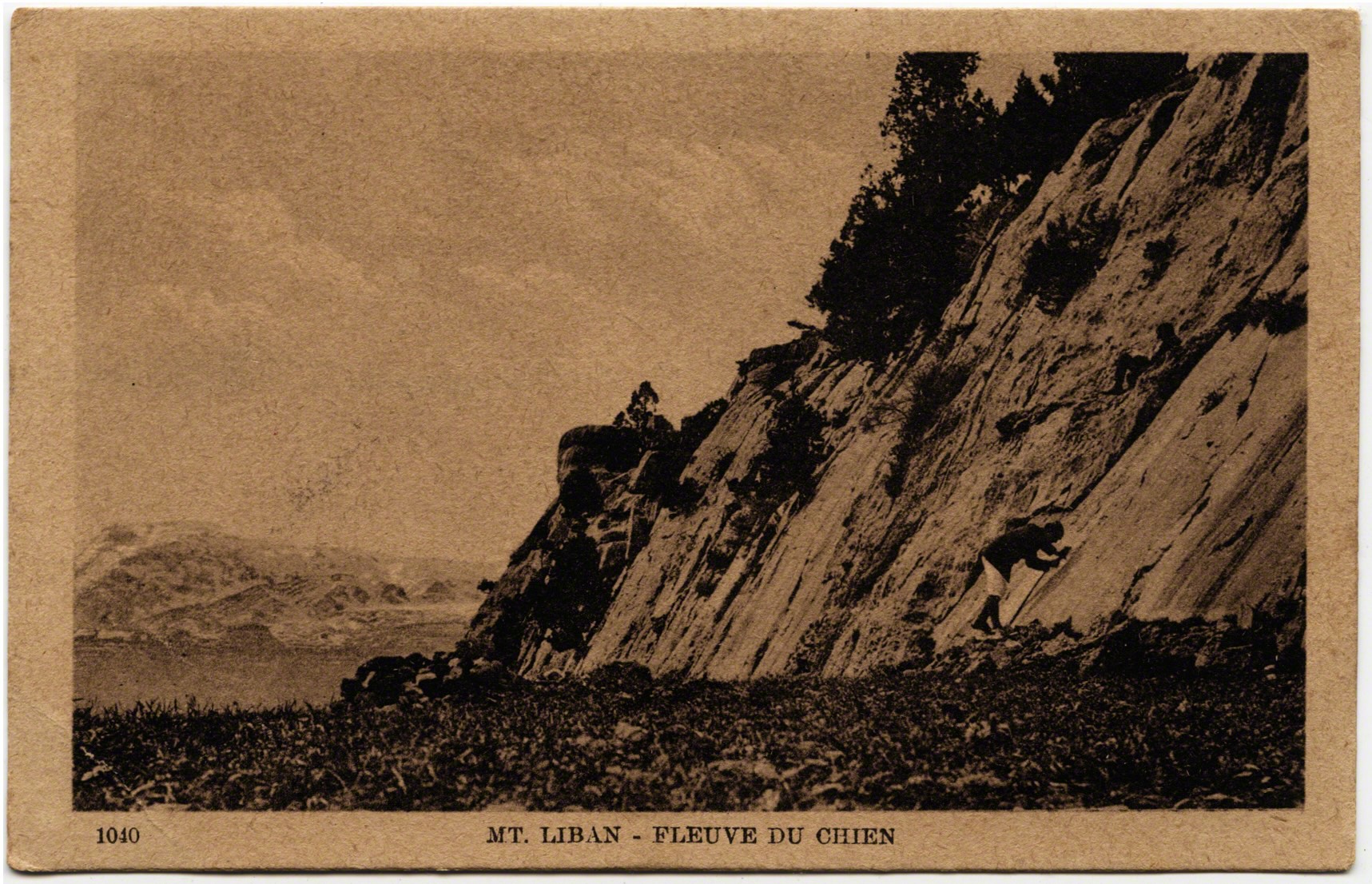

What unites these many stories is the continual passage of invaders, strangers, and foreigners on what amounts to a small path alongside the water and an 80-foot limestone rock-face. As the plaque at the site from the Ministry of Culture notes: a “traveler in 1232” said that “a few men could prevent the entire world from passing through this place.” The historian Hitti echoed this by saying how the “mountain cliffs plunge straight into the sea, providing a strategic situation for ambushing invading armies” (Hitti 1959: 15). Thus it seems auspicious that in hundreds of kilometers of coastline that the natural morphology squeezed passing between river, sea, and stone.

This rock face became an “open air museum” of some 22 stelae (stone carved tablets/faces) from various rulers, kings, and conquerors who crossed this river (Hitti 1965: 134). Men commemorated their passage, and that of their armies, with prayers, proclamations, and iconography that would remain as visual reminders of their presence. Some of those that transited were Pharaoh Ramses II who was famed to have sought out the timber from the cedars, the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar in around 500 BC, Assyrian King Assarhaddon, Romans, Greeks, and many Europeans. The National Geographic Society noted the “proud inscriptions of conquerors who have passed this way since history was holding a rattle” (1923: 123).

In more modern times this included British troops in 1918 and the French Général Gouraud in 1920 on their way to Damascus in the last days of the Ottoman Empire. In 1946 the Lebanese created a memorial at the site on the eve of independence to mark the occasion when all foreign troops were withdrawn from the country (see Volk 2010). The most recent addition was in 2000 to commemorate the liberation of south Lebanon from Israeli Occupation. Thus, the site is a space of national commemoration, a log of mobility, and a contested point of symbolic control.

Many postcards commemorated Dog River from many views. This memorization coaligned with Europeans’ versions of history, as postcards stimulated and connected to a Victorian propensity for “acquiring, classifying, and arraigning specimens” (Guynn 2007: 1162). As well as the numerous travelogues of visitors to the “Holy Land” steeped in orientalism.

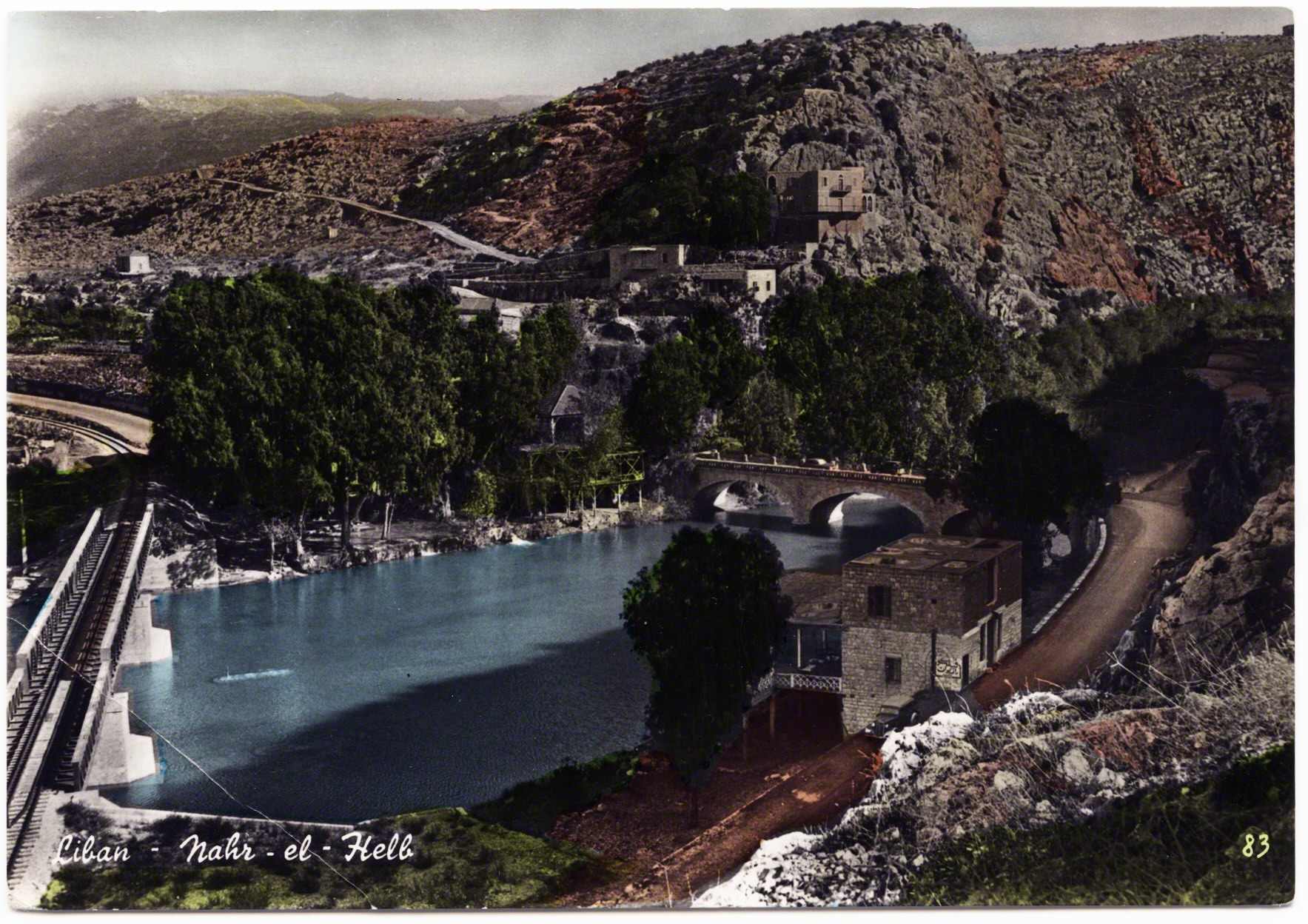

Up the bend of the river is an old stone bridge built by the Mamluks that overlooks newer infrastructures that span the river. As the years passed changing views of postcards paid testament to the French Colonial power in conquering the nation, nature, and as indication of their engineering prowess through the establishment of a series of roads, bridges, and railroads. These French designs and achievements honored on the postcards seem to become as much a focal point of the postcards as the history of “Dog River.”

These infrastructures bearing witness of new control of mobility in this symbolic location. Interestingly, the bridges here are metaphoric and real in how they spanned the river at this auspicious site. The river remained the same, but with a different riddler controlling passage. Were the Mandate officials were now like the “dog,” determining who, and what, could pass ? Were these infrastructures indexing newer ways of marking one’s presence similar to a stone etchings? Like many colonial representations in the same time period worldwide, postcards became a way to signal the imperial authority, their capabilities, and certain views of modernity. As such, postcards became a “constant reminder of the imperial condition that establish the basis for modern cosmopolitanism” (Mathur 2007: 100, & see Mathur 1999).

From my own appraisal (and collection of postcards of the Levant), Dog River slowly started to recede in the visual register as the views turned northward. New sites up the coast signaled new attractions and priorities. There are fewer and fewer (re)productions of the river and stelae by the 1950/1960’s.

A UNESCO publication of “Memories of the World,” imagines these stelae as a testament to Lebanon's "relations with the rest of the Middle East and the West" (2012: 176). Volk notes that Dog River references the Lebanese’s "multicultural past, and their heritage as a cross-roads for and between ancient civilizations” yet it also begets noting that being at the crossroads “has not necessarily had a unifying effect” (Volk 2010: 19). Crossroads are powerful but volatile.

Given this, how might we think of these stelae similar to postcards - as “graffiti” chiseled in stone - in an inverted likeness of a postcard? Rather than being mailed from afar to mark the “having-been-in-this-place,” the stone marks one’s passage and presence in the location. Both the stone wall and the postcards quintessentially index mobility: the movement, a passage, and a visual memory of it. The plaques and etchings at Dog River monumentalize a “being-in-place” at the river, while postcards do similar work but through a circulation and view that lends one to think the sender was there.

In this way I’m positing postcards as a juncture between an impression and an expectation. This impression has a fixed boundary and frame through its composition, just as it is imprinted in the likeness of an image, a momentary imitation. More importantly, this impression presented boundaries of our senses for thinking about place. This could be a common stereotype of the people, city, or ways of life that transpired in the “real” location that was depicted. Postcards could reinforce these conceptions of place, or challenge them. Yet at the same time, through the postcard’s propulsion, there was a public proclamation of this location. Through a sense of desire, realized on a vision from the postcard, it might say “I went.” “You should too.” “Look what I saw.” “Wish you were here.” It also might have an x marking where I stood. An index of person in place on a mass produced surface.

However, like any image, there is a deception in postcards. A duplicity, because they are duplicated. It signals one’s location and hints to a view, a landscape, or what one might actually have seen - but didn’t. My eyes met with a likeness depicted from the card, or an idealized version of that vista, outfit, or sculpture - but wasn’t. The sunset from a different day. So there exists a certain objectification and representation that becomes essentialized through the genre of postcards and in this act-of-being-there (see Sontag 1977).

In this regard, Kracauer is instructive in framing a relationship of imagery, place, and mass-media through his meditation on surfaces. In a series of essays grouped into the Mass Ornament (1927) and On Photography (1927) Kracauer questions the interconnections of pop-culture, distraction, and changing relationships at this same moment in European industrializing societies. He said that the “ornament” was a “mere building block” of mass culture and was the removal of the individual in cultural production (1927). This faceless repositioning through modernity presented “a new type of collectivity organized not according to the natural bonds of community but as a social mass of functionally linked individuals” (Levin 1995: 18). As such, ornaments were made of “insignificant surface utterances” and they “resembles aerial photographs of landscapes and cities in that it does not emerge out of the interior of the given conditions, but rather appears above them” (Kracauer: 1995: 76-77).

Koch wonders how much the “surface,” in Kracauer’s work, is merely a way to conceptually connect back to his concern of the masses/mass ornaments (2000: 28). Given this, how might we understand the role of the surface if all of society dreams in the “form of its ornaments…the dream thus illuminates the dreamer” (Koch 28). The framing of the postcard becomes the vessel into which we pour our own desires and projections - just as they are projected out into the world.

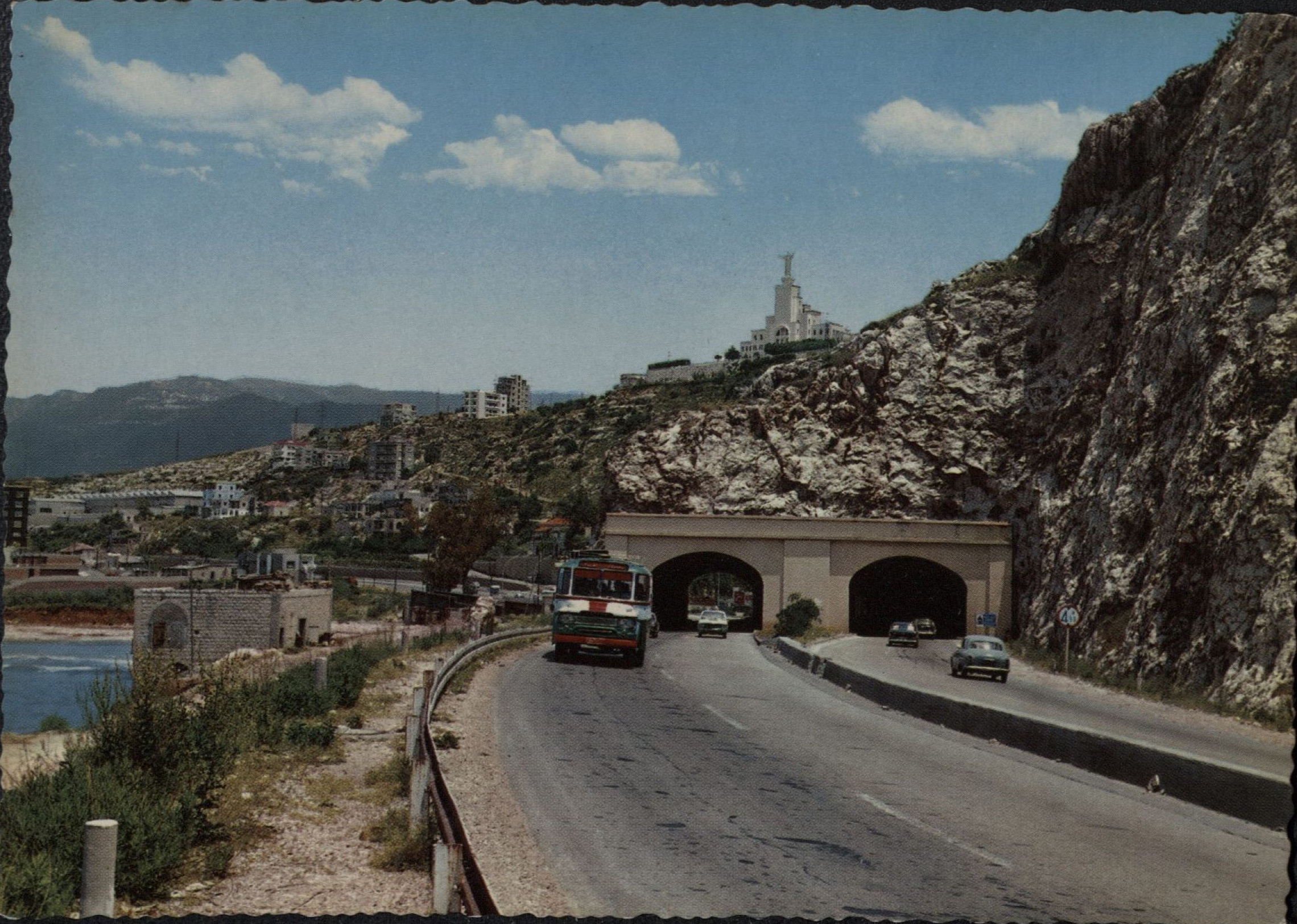

This final card is of a highway tunnel. I runs directly under the oldest inscriptions from thousands of years ago. To accomdate greater mobility at this bottleneck of Dog River, the Lebanese State bore through stone to create a modern highway. This passage now takes us to the next actor above the Bay of Jounieh.