=========

I Postcards:

Place, Photography & History

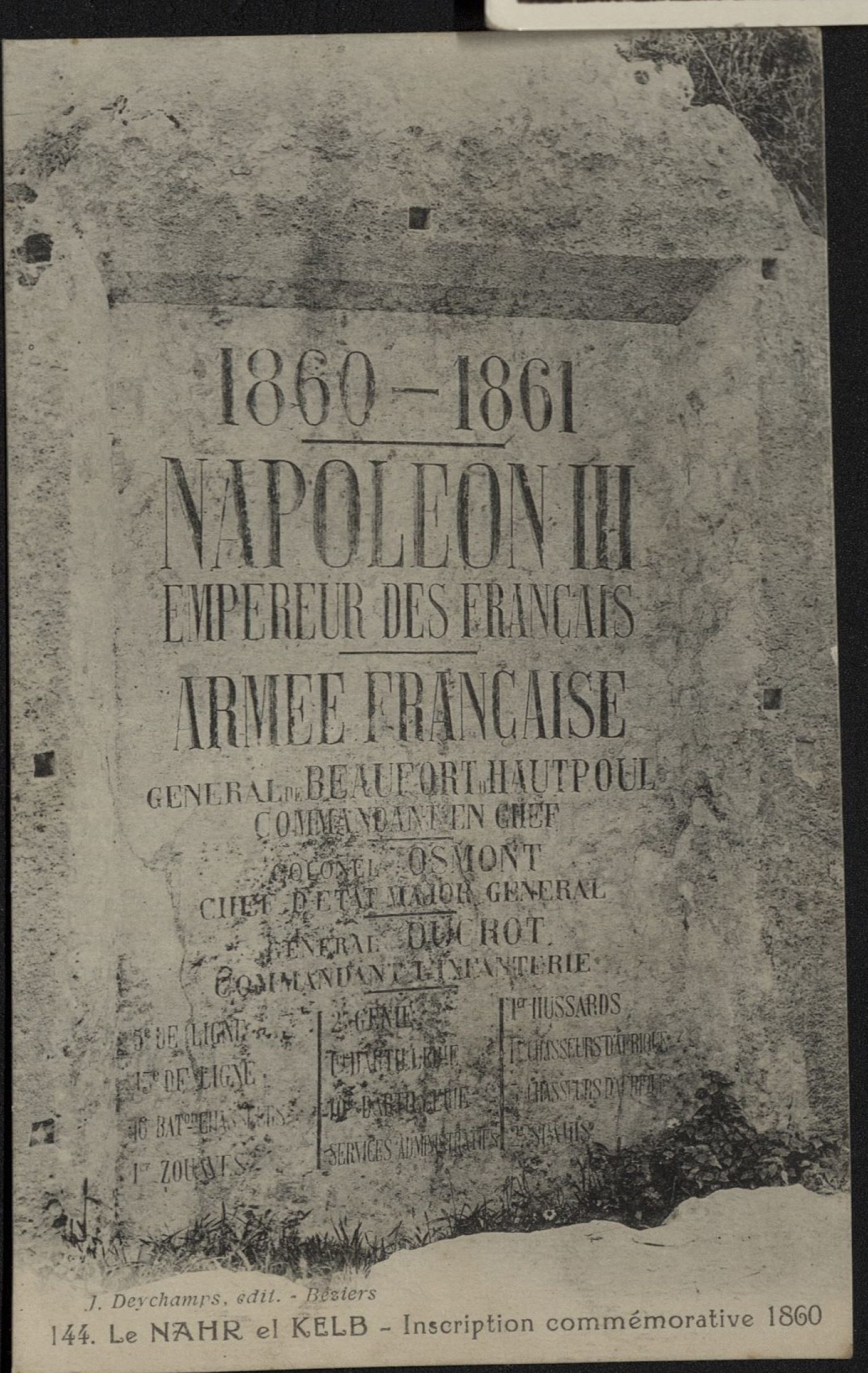

Roughly 12km outside of Beirut is a commemorative plaque on the side of a hill placed by Napoleon III and his army in the year 1860/61. Today it rests at street level almost kissing asphalt off an exit ramp of the main highway running north to Tripoli. Given his reputation, it might come as little surprise that Napoleon mounted the memorial of his passage through Lebanon directly over an inscription from Pharaoh Ramesses II from Egypt, carved in 1271BC.

Napoleon’s act of one-upmanship concealed the previous conqueror, but there are 21 other inscriptions, carvings, and plaques that dot the limestone rock face at the mouth of Dog River (نهر الكلب) This location forms a visual and imaginative marker of mobility, passing armies, imperial and colonial projects, and the making of the Lebanese state through tourism. As such, it represents a site of commemoration realized though a collection of inscriptions on the landscape (see Volk 2012, 2008). Many legacies and events are memorialized in stone.

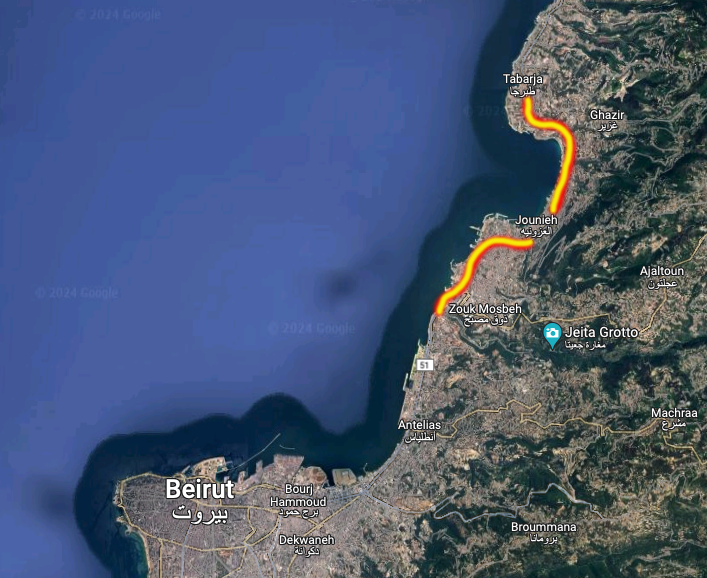

This piece situates the context and regional importance of postcards in Lebanon to think through progressing visualizations of place. The views presented here span a small 7KM strip of land from Dog River through the bay of Jounieh. The sights on these postcards signal changing occupations, modes of consumption and movement, and the development of the modern nation state of Lebanon. They offer some 7-km-glimpse into an 80 year span of postcards.

Inspired by the work of Arreola on the border between Texas and Mexico, there is a “serial scripting” that happens by juxtaposing multiple views of place in time (2013). To do this through postcards then creates an “assembled view of places, spaces, and monuments, that become worth noting - while others fade away” (ibid - my emphasis).

This analysis will also explore the “surface” of the image as inspired by the work of Kracauer (1929). I am combining these two terms to think through these postcards in a serial surfacing. The scripting proposes a sequence to view the images while surface highlights the printed form and materiality, surface of the nation in the land, and surface linked to the indexicality of what they projected.

As I will argue, these postcards do not serve strictly as an archive of moments, but were part of an evolving and changing landscape of meaning and mobility to/through Lebanon. They create views of locations which are permanent, unlike the actual landscape, and do so onto a representation that is mobile – and meant to be a mobile representation of it. As such, these postcards created a triangulation between place, image and viewer.

This piece begins by briefly considering the medium of postcards and photography in the regional context of Lebanon. What follows are (3) image based “actors” that emerge. Each from the within this 7km strip of coastline. These actors are created through a series of images that fold on top of one another, in progression, like flipbooks through views and times. They create movement and directionality in space/time because “places are always unfished, deferred and lacking a unity or order established through representation” (Hetherington 1997: 187). The hey-day of postcards was a time when photography exploded and technological advances delivered bodies, ideas, and things around the world more quickly. Thus postcards too were built onto, and represent, these circuits of mobility. Important questions concerning modes of production, local photographers, publishers, colonial agents, individual postcard messages, and the various publics meant to consume such images are salient - but largely outside the scope of this analysis.

An analysis of postcards is not just to conjuror trivial visions of the “past” or raise nostalgia. As images they are performative flashes which render certain views of place visible, frozen, but index a changing nation, reveal power relations, and often typify through their views. The perspectives they present creates a “unique vision because often the same locations and landmarks get photographed and reproduced generation after generation, enabling a sequential perspective through time.” (Arreola 2013: xv).

What developed across decades were eddies of locations in which bodies and visions were stuck. These images do not attempt to recuperate the history of these times, but through a visual progression, in the material medium of postcards, this analysis explores how place was represented and constituted through tourism and movement. Through this the three actors emerge: a river, a virgin, and a casino.

After WWII, and in the ensuing age of mass-tourism, postcards became intrinsically tied with “tourism” and encapsulated a view/idea/vista/stereotype of a place. Yet, what is the role of this imagery, through the sub-genre of postcards as time passes? How do these images, once released, contribute to imaginations of a place as they circulate and move? Or as they hold of view of something lost, another time? I ask the reader to think of each postcard as a drop of water. Droplets fallen from the sky that might collect, flows, conjoin, and gain momentum. Perhaps they run down the landscape over existing channels and carve new paths through stone. Might they be part of what forms a river of our thoughts? Origins and destination are blurred.