=========

III Landscape of a Virgin

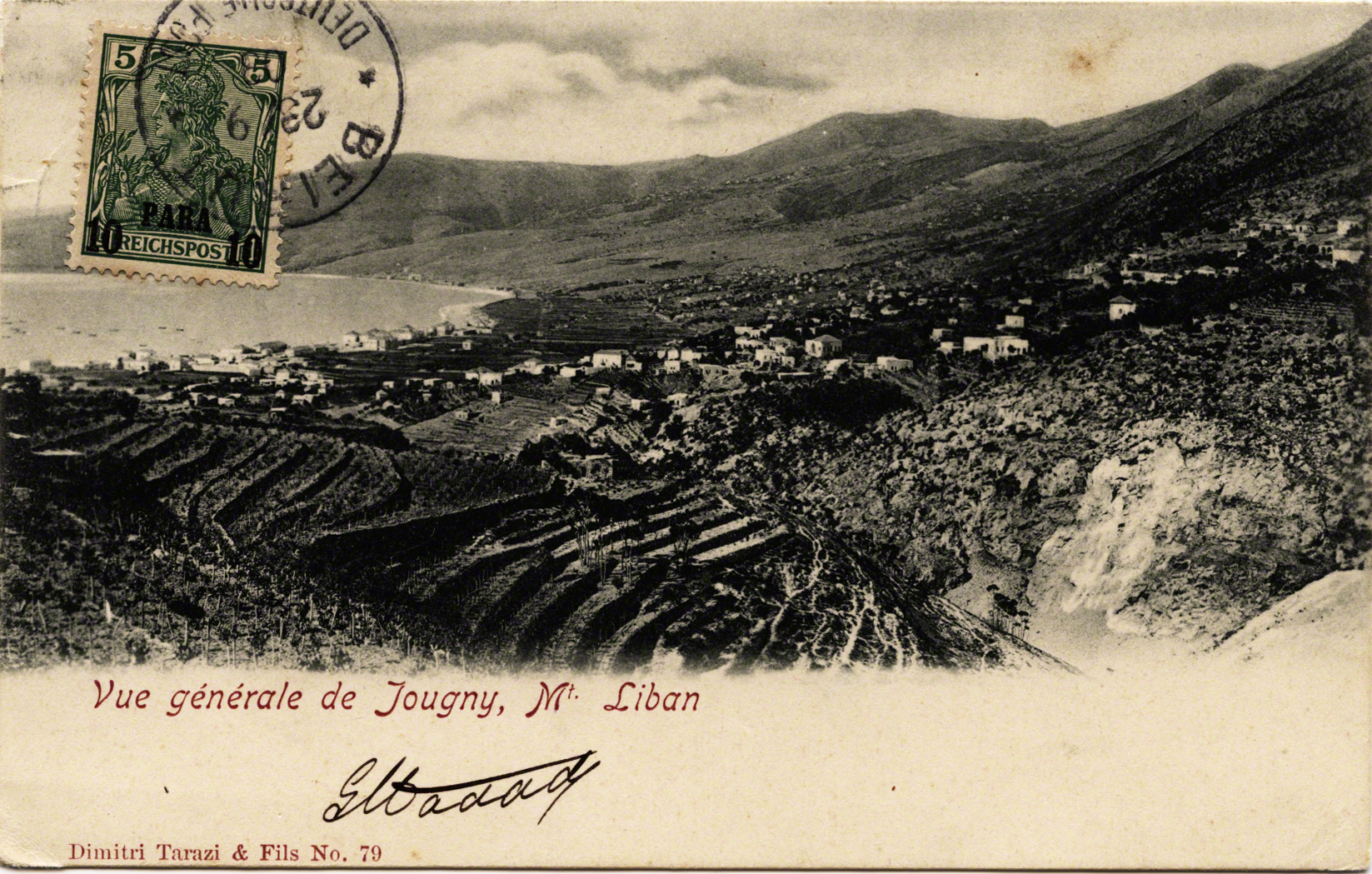

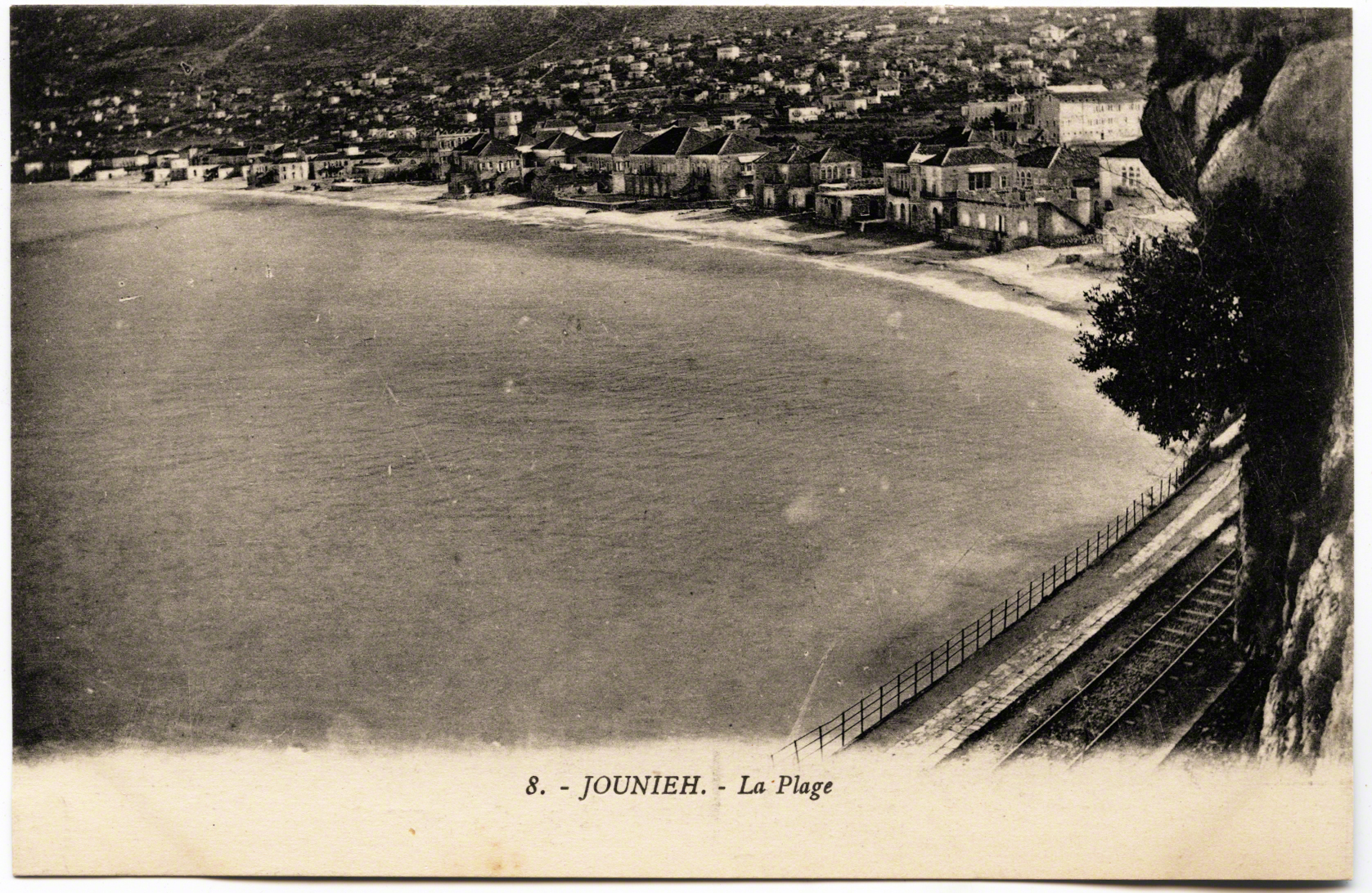

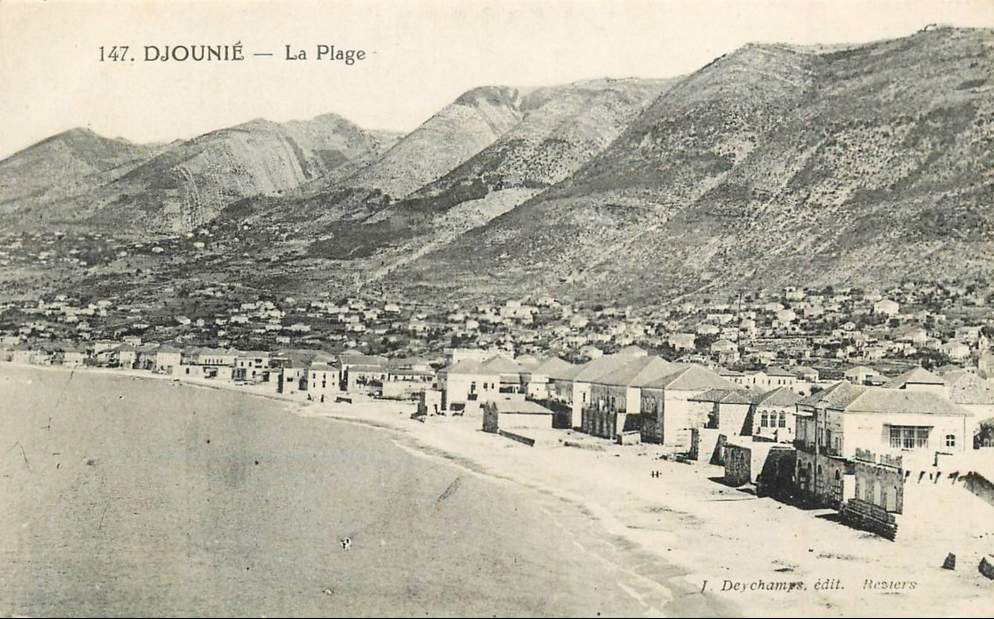

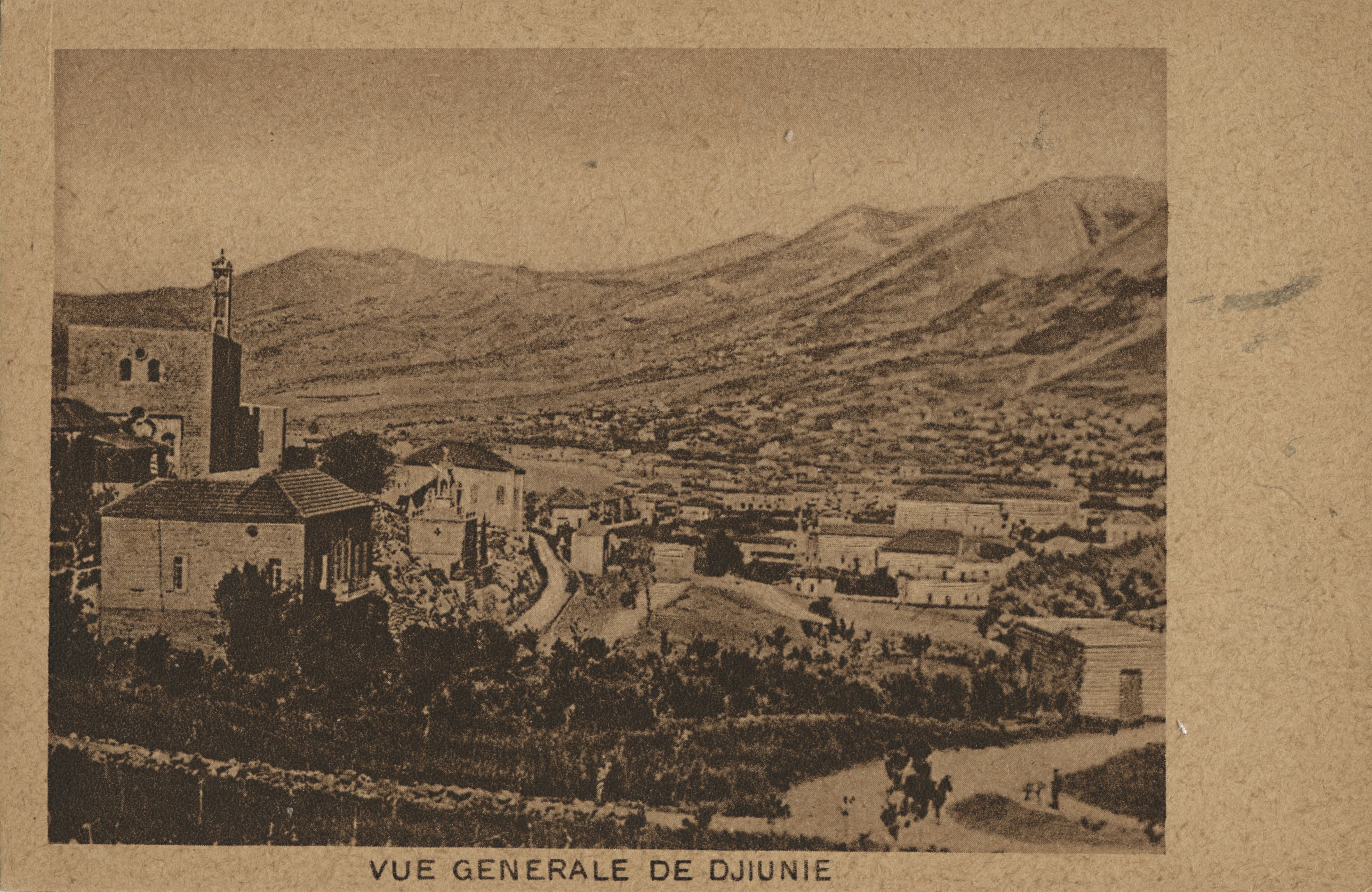

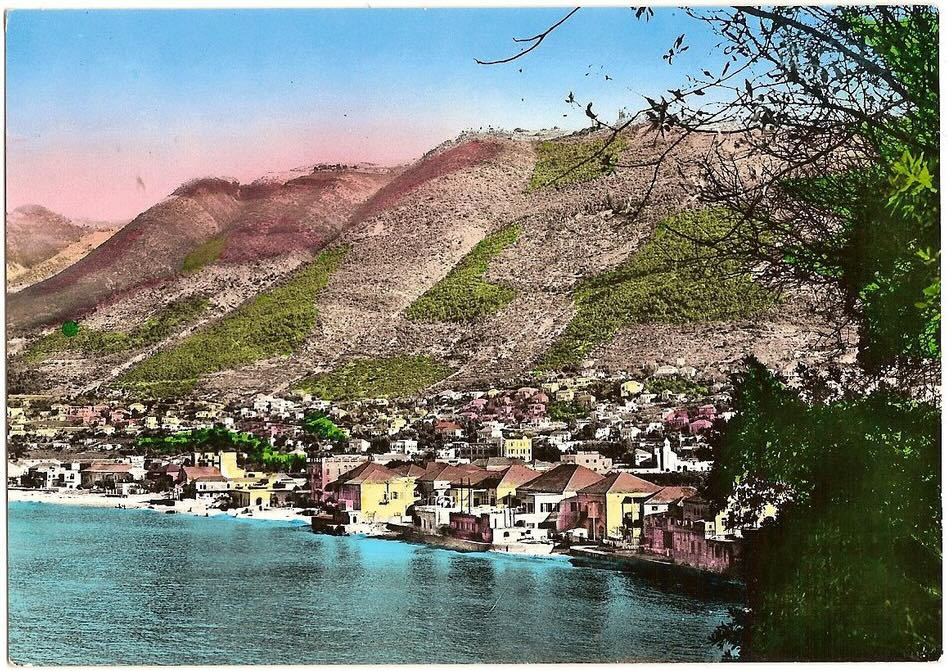

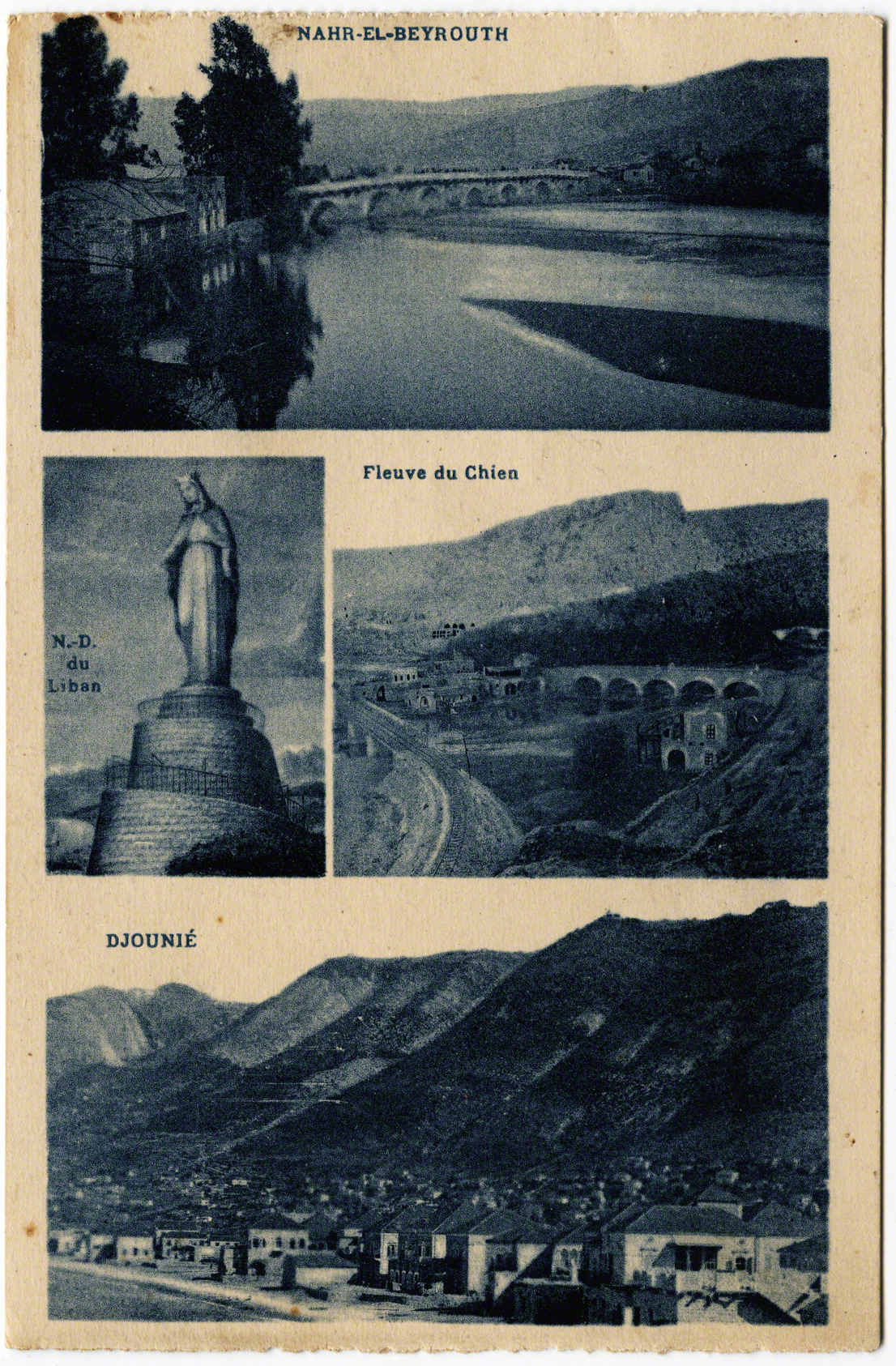

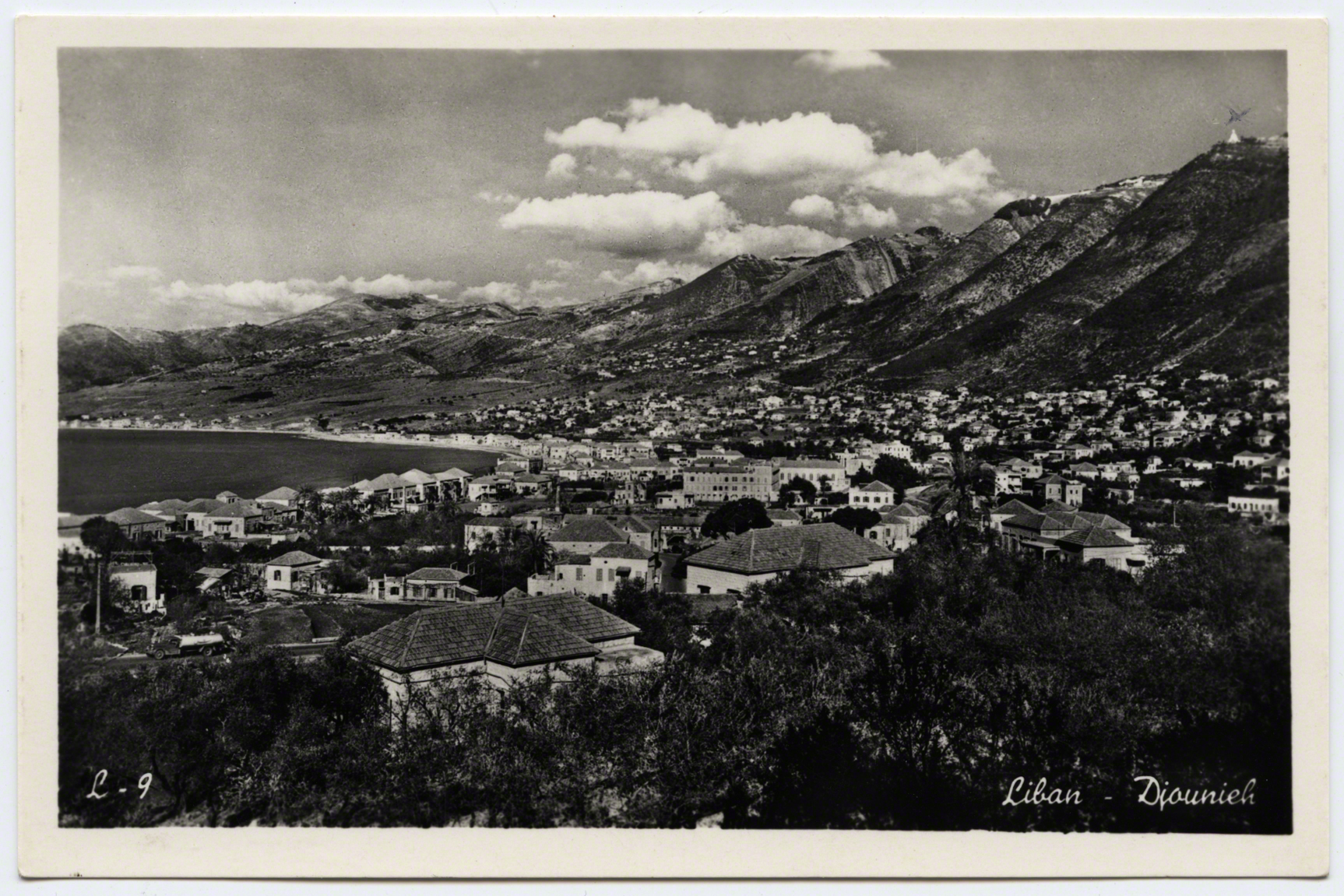

Heading Three km north of Dog River, one would turn east into Jounieh. The landscape was sparsely developed and it was a small fishing village at the turn of the century. Within years, in the distance, above the bay, an effigy of the Virgin Mary would come to overlook this area.

This flipbook presents the views and role of the landscape to consider the relationship between land, nation and the bodies that populate it. “Above all,” Tilley writes, the landscape “represents a means of conceptual ordering that stresses relations.” (1994: 34). The postcards here illustrate a serial scripting of the landscape and sedimentary layers, built upon one another. They crystallized certain views not just visually, but conceptually. In this way, landscape becomes a “cultural process” and tourism is a lens to think of these changing views and paths (Ingold 1994: 738 & 2007).

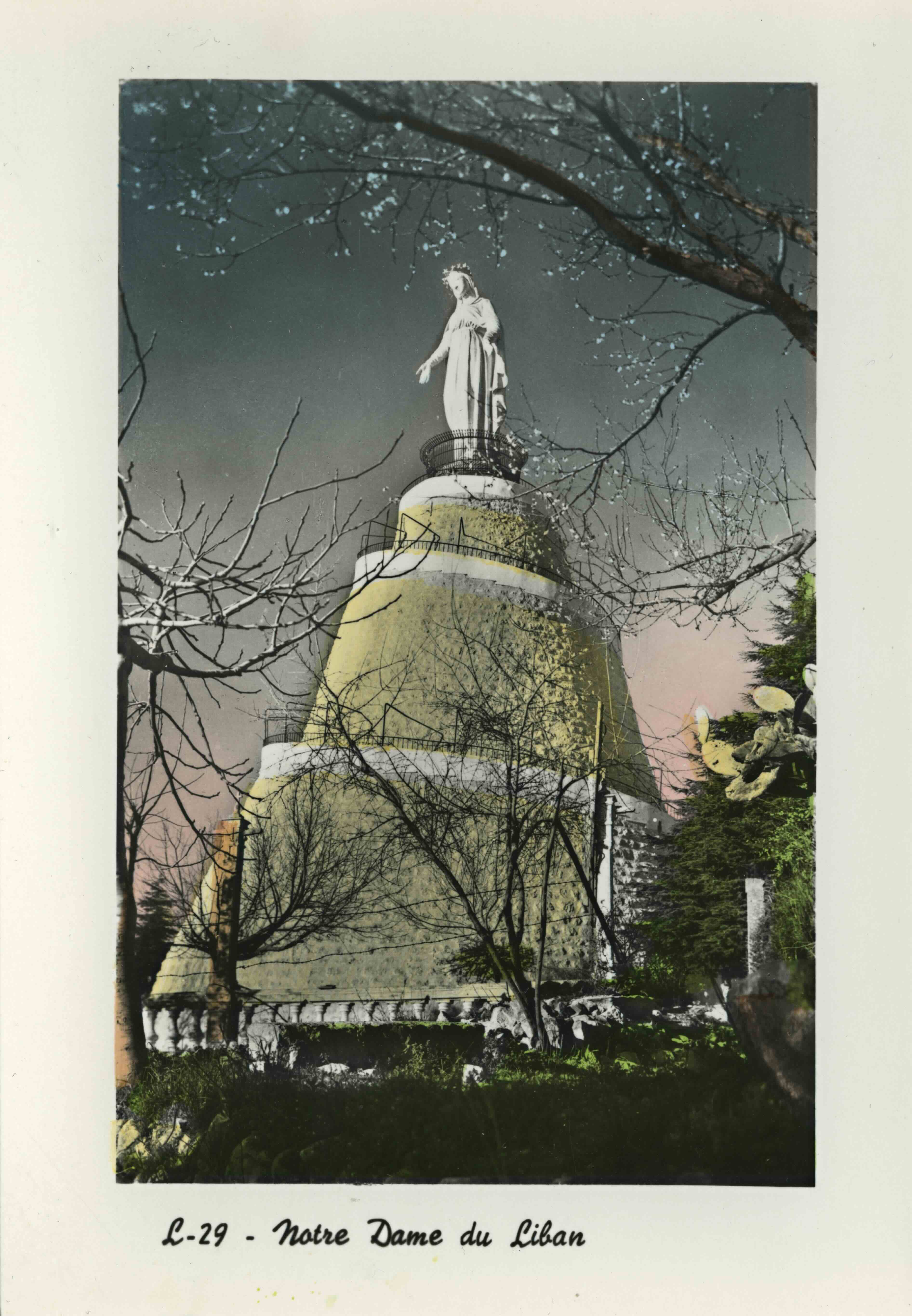

In 1904 the Maronite Patriarch Hoayek conceived of the idea to erect a statue of the Virgin Mary to mark the 50th anniversary of the “doctrine of the Immaculate Conception” (Durward 1908: 753). Mary was built in France and mounted in Lebanon in 1908. The statue was placed above Jounieh in a village called Harissa, which was the location of a long standing convent.

John Burckhardt, a pilgrim to the "Holy Land" from England, noted of the village in 1822: "Harissa is a well built, large convent, capable of receiving upwards of twenty monks" (184). Another priest, in 1830 noted the view from this spot in the terraces of the convent: “is extremely beautiful, commanding the bay of Kesrouan and the country as far as Djebail (Jbeil) on one tide, and down to Beirout (Beirut) on the other. Near it is a miserable village of the same name” (Conder: 159).

The Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Lebanon, would eventually take a shorter name. Her location became her name - Harissa - just as her presence indexed those who wanted to mark this area as a solidly Christian territory. Watching over the slopping lands she became an important site of pilgrimage and visuality. We not only see her, but imagery as if from the perspective of her eyes, the claim of control over which she governs. Jackson’s work on “vernacular landscapes,” in which a view is indexing a political, but also a social world, is relevant to Harissa (1984). Her perch on the mountain, and the huge number of postcards around her index, over and over again, mark the presence of Christianity and the development and urbanization of the Bay of Jounieh.

The placement of this physical statue is significant but so is the linkage of her body to the landscape. The landscape on which she emerges, to the larger body of the nation. Such imagery might make one think that the nation is filled with certain types (Christians) that live below her feet. The images of her, and the bay of Jounieh, are linked henceforth in postcards.

Historically there was always an interplay between photography, landscape, and the way in which the nation was built (see Taylor 1994). These postcards are then an outward face and representation of certain vistas/views. In the context of Paris, Schor juxtaposed postcards in order to illustrate aspects of the “discourse of the metropolis” (1992: 195). She showed ways in which the city was changing, but also how those changes fed back into narratives of the place itself, folding meaning and vision together in a reconstitution (ibid). We might also question the landscape and environment here as foreground and background, what was being accentuated and focused on while what was auxiliary filling the background. "Foreground actuality and background potentiality exist in a process of mutual implication” and daily life will never match those “the idealized features of a representation” (Hirsch 1995: 23). Thus the foreground and background became an interplay of possibility and promise.

There is much more to say for the role of Christianity. How much did these postcards contribute to sectarian identities of belonging and religious ideologies? What would other faiths think of Harissa being reproduced as a face of their shared country? What about Christian entrepreneurs profiting off building a tourism industry, or the the long and complicated ideological/religious orientation of Lebanese Christians with France? Lest we forget that Napoleon’s journey in 1860, so boldly marked at Dog River, was to protect the Christians in sectarian fighting, the French General Gouraud, in 1920, proclaimed Lebanon a "safe haven" for Catholics.

Take for instance these three following cards which play with scale: first, before the days of Photoshop, she looms totally out of proportion over the bay as if to increase her prowess; second, we oddly see a view of her looking south, as if she were looking over Beirut in the distance; third, the view she might sees from her marble eyes. The entire bay of Jounieh is visible from North to South..

In addition to the powerful work that these cards do in staking a claim to the land and nation, many of these postcards became for Diasporic consumption. Earlier cards were often produced for European (colonial/imperial) interests but many waves of Christian emigrated worldwide and they came back to Lebanon as a form of tourists. In terms of the landscape these postcards also do other work, they create new paths. Postcards provide coordinates in the world, or simply put, they are “geographic information” and “representations of place: the scene of the seen” (Arreola 2012: XV, 2). Thus, they speak to the paths that we traverse as mobile, touristic, bodies, as well as show us the “idealized” routes on which we should remain in order to “see” these same views. A path implies not just where we put our feet, or the ground which bears the markings of how narrow, deep and worn the land has become, but paths are also a cultural act. They guide us. What does it mean to go off a path - to stray, get lost, or divert? Paths are like channels that normalize a transit, lines, or directions. If paths guide our movement then postcards serve as mile markers that position us. They signaled where we are, where we want to be, but also where we should be. In this regard, part of what I posit here - and explore visually in a digital project (related to this piece A View from a View) are how we become trapped in such paths, such narrow definitions where our bodies swirl in an eddy that is crafted with intention for a tourism “industry.

By the age of mass-tourism another concern arises, where do these paths lead to? One of many places that would develop in the bay of Jounieh was the téléphérique. It connected visitors from the seashore up to the feet of Harissa. It was founded in 1965 and was owned and operated by Compagnie Libanaise du Telepherique et d' Expansion Touristique. Private entrepreneurs would pour money into the development of new paths, sites, and sights for mobile bodies. During this “Golden Age” of tourism in Lebanon, Jounieh developed a wider and more robust touristic economy, not just as a destination, but also as a midpoint to other sites in the nation (i.e. Cedars).

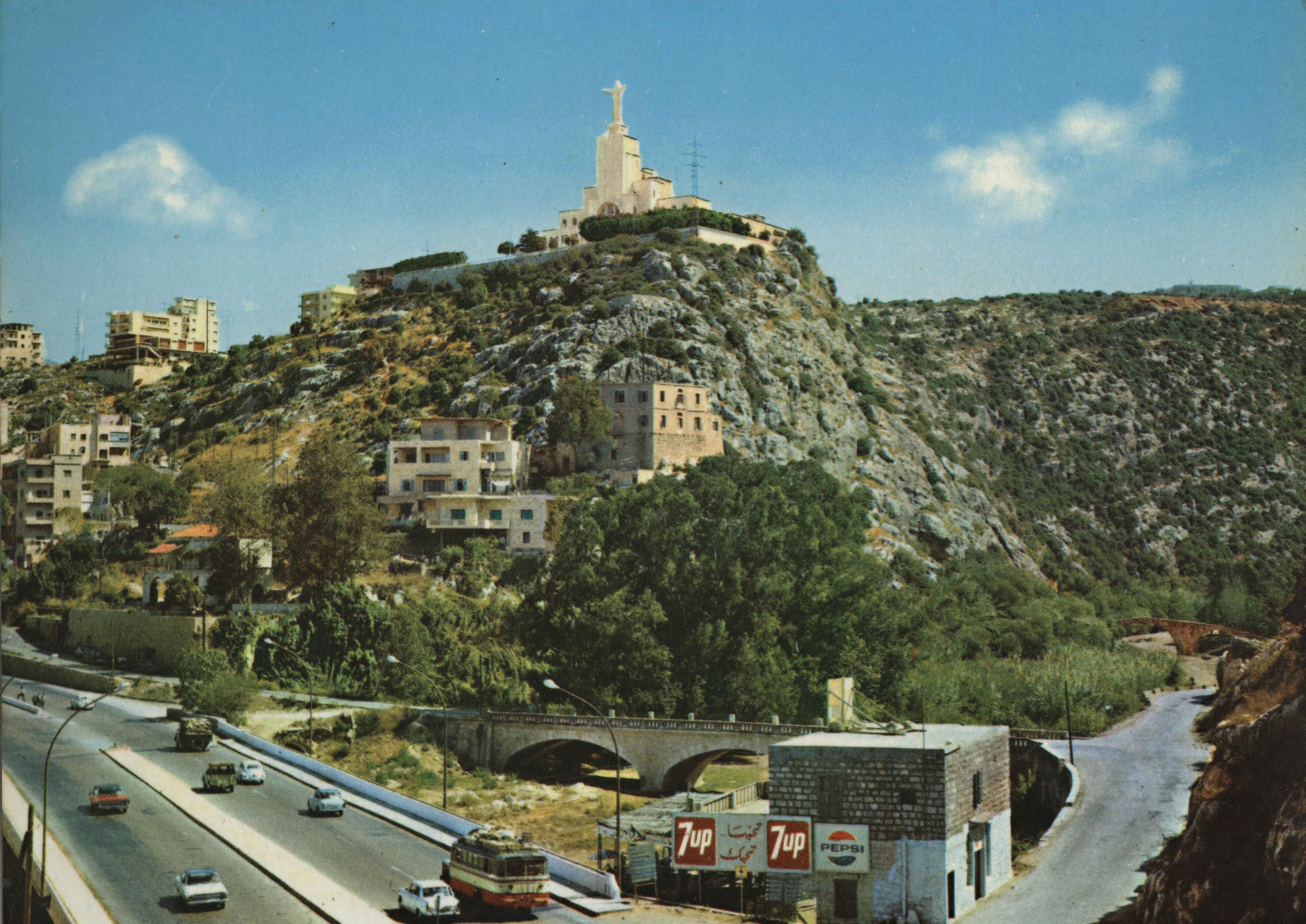

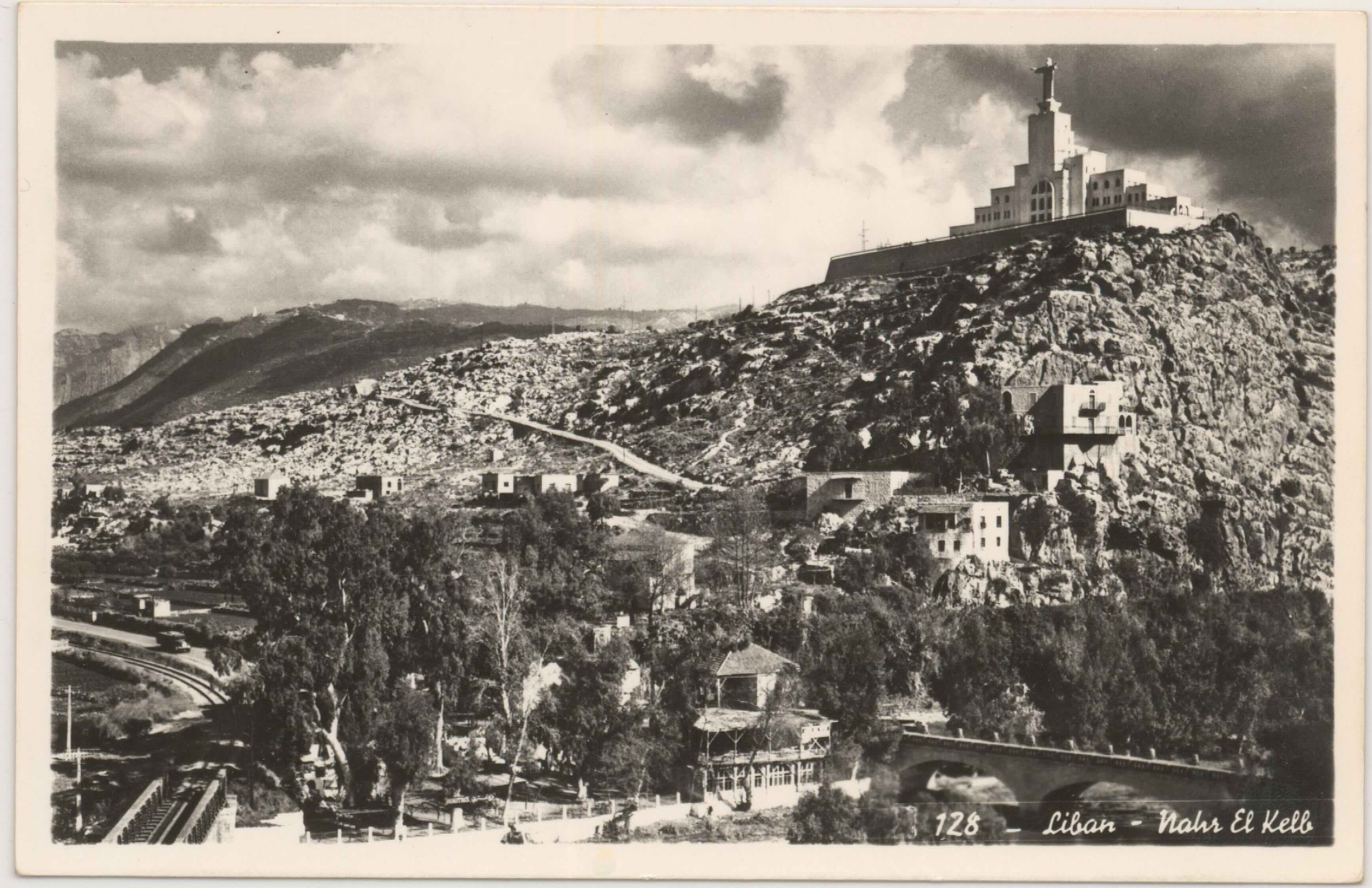

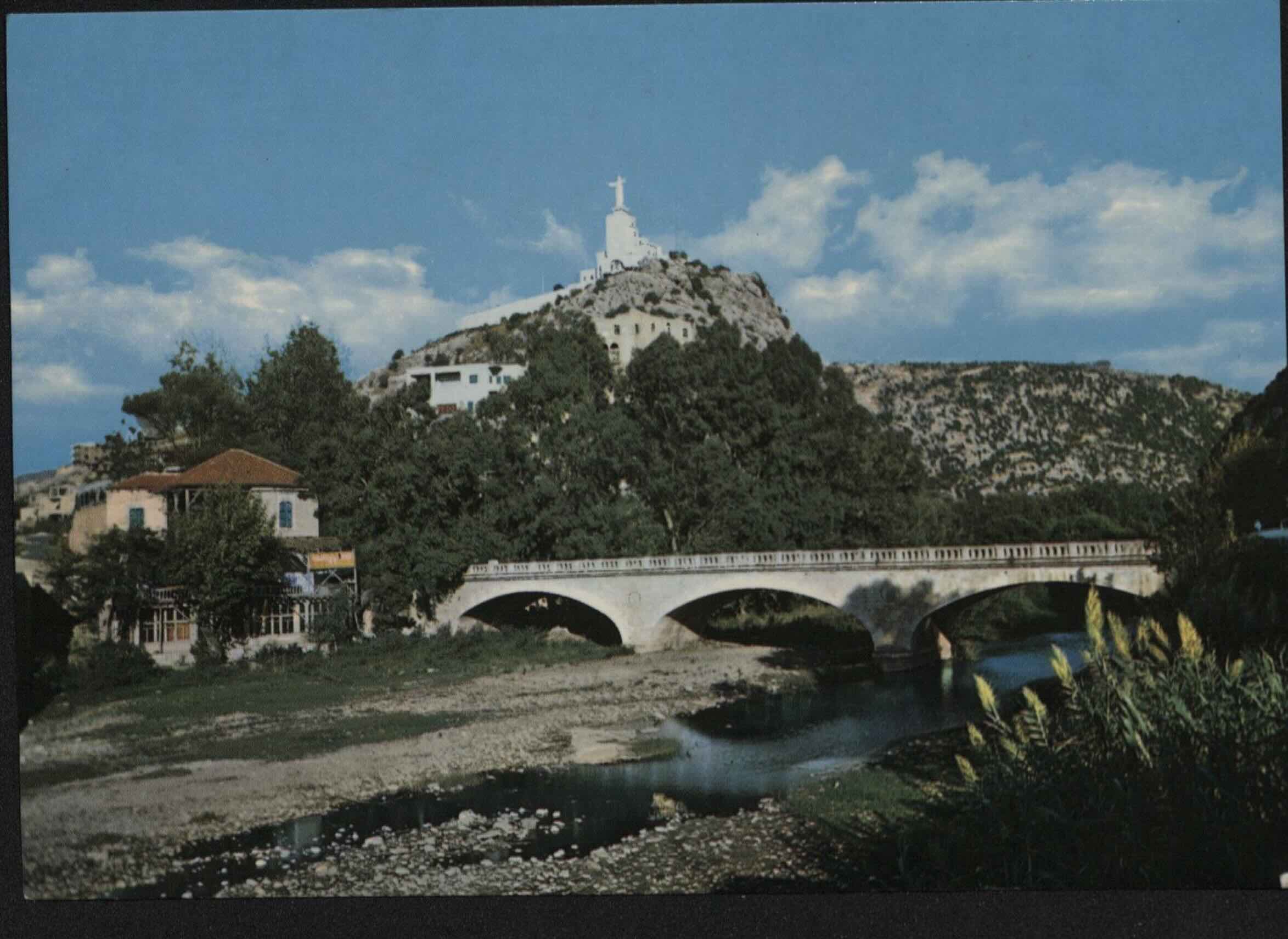

Ironically, this flipbook of images returns to Dog River. Before the téléphérique was initiated a statue similar to Harissa was built on a hill on the opposite side of most of the stele. Jesus the King (Yessou7 al Malak) was built in Zouk Mosbeh, on the Northern side of Dog River. It was a statue of Jesus, with his arms flung wide open. Just like his mother a few kilometers up the road he faced westward out to sea. Welcoming and watching - or perhaps warning, like the original dog statues. In this image a modern highway took the place where the railroad had once stood. The French and Mamlouk bridges both step back in into the depths of the valley, stagered bridges of time.

This location from where Jesus the King rose was historically a site of an old monastery and church. As the myth goes (from the Lebanese Ministry of Tourism), in 1895 during the Ottoman Empire, Brother Yaacoub Haddad was on his way to take his monastic vows and he passed the aforementioned inscriptions of Dog River (MOT ?). He said “Christ must have a record in this place, more important than the written and engraved remains” (ibid). It seems he thought Christ must have the larger word in the graffiti battle in stone. Thus, decades later Brother Haddad bought a piece of land on the opposite hill and opened his church in 1951.

He commissioned an Italian artist to make the statue of Jesus which was 12 meters high (ibid). It was installed in 1952 and there is an elevator to the top of Jesus’s head (Kuntz 2000: 155). One might suspect that Jesus the King was partly an effort, akin to Napoleon, to superseded the names of other kings’ nearby. While the views of postcards presented here in the Landscape of a Virgin run laterally, inwards, outwards, and to the coast – both Jesus and Mary have a position on the mountains overlooking bridges, roads, rivers and the sea. Seemingly keeping track of mobilities below, while indexing the shadow of a religious community’s control.