=========

VI Path to a Casino

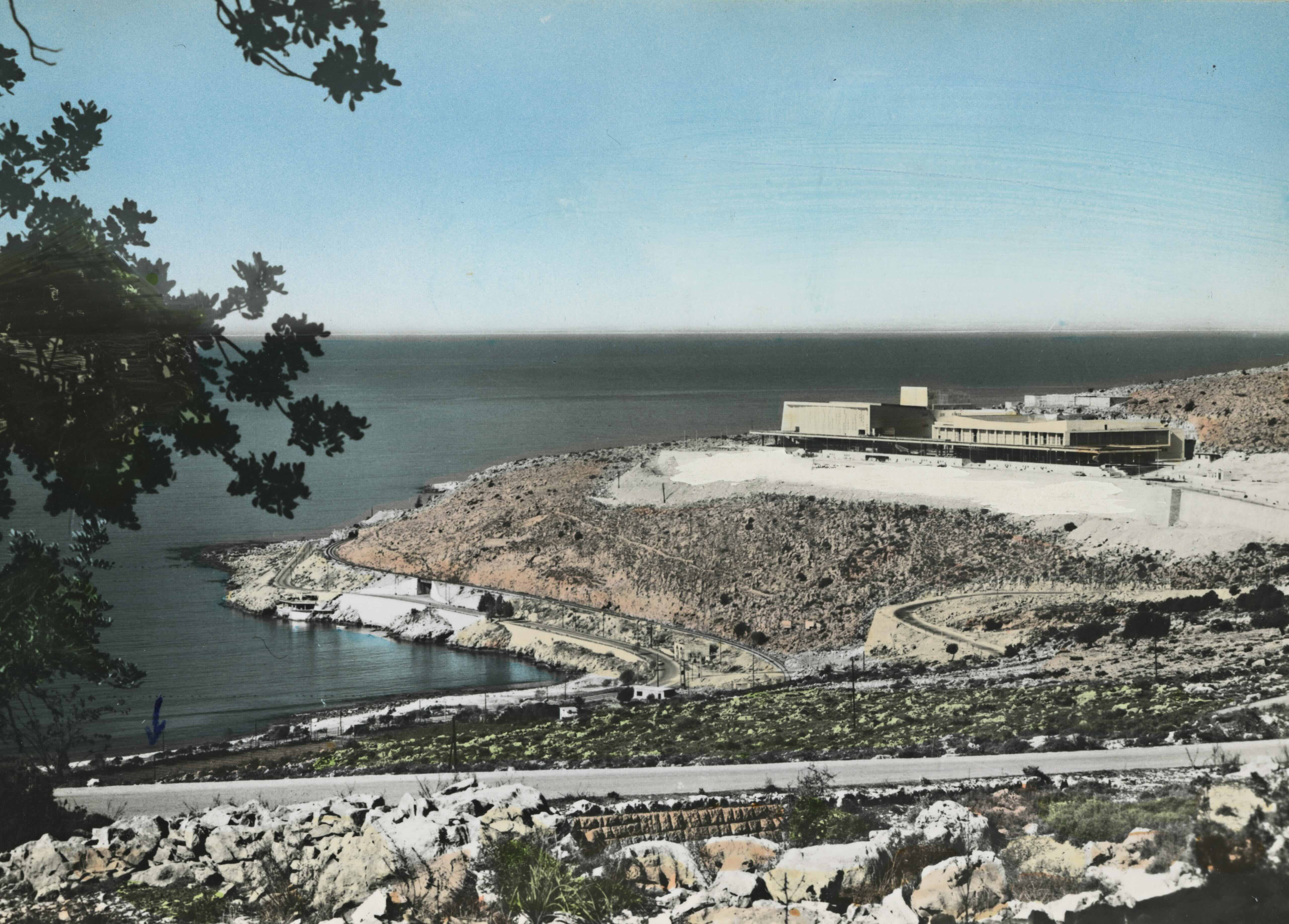

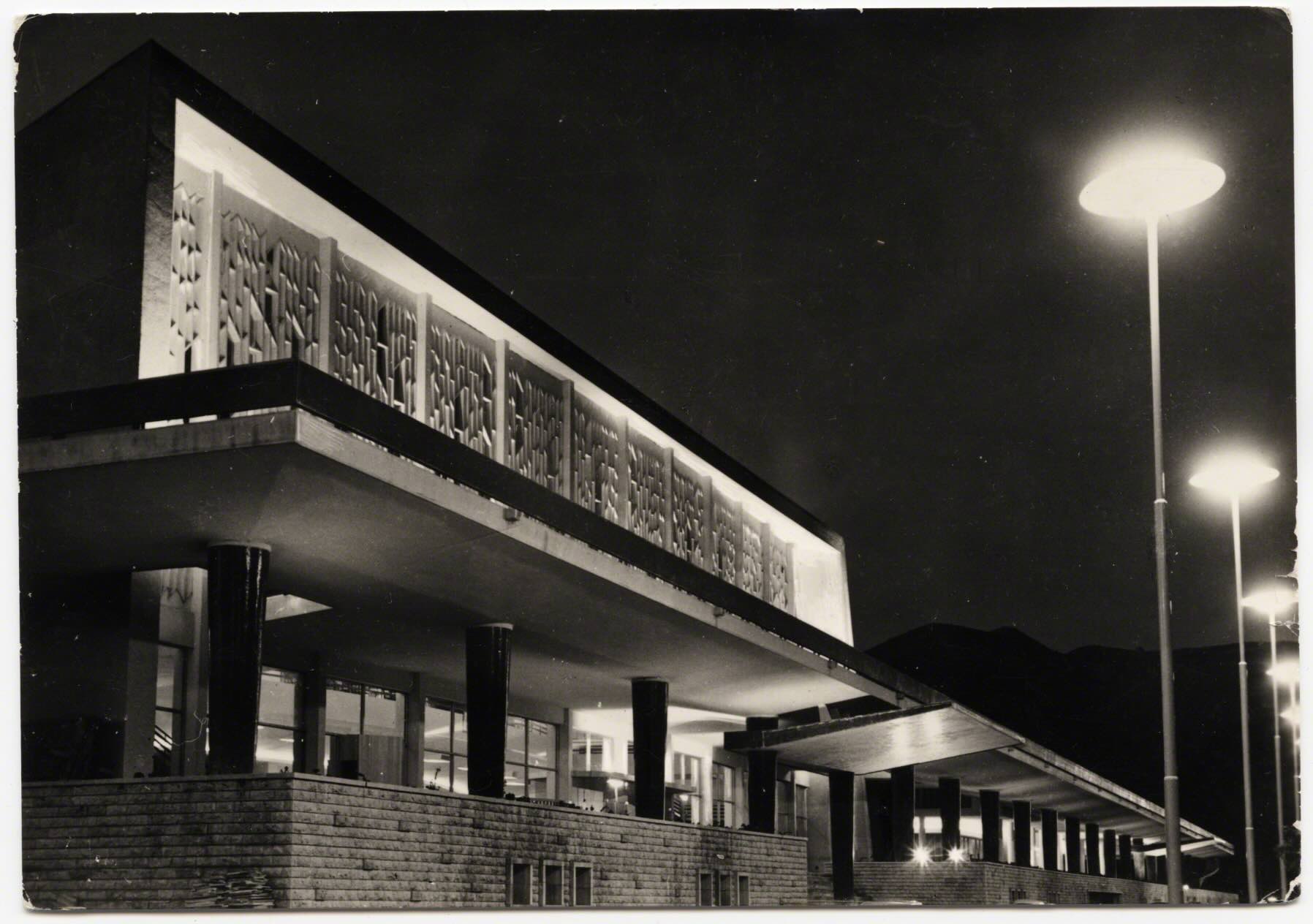

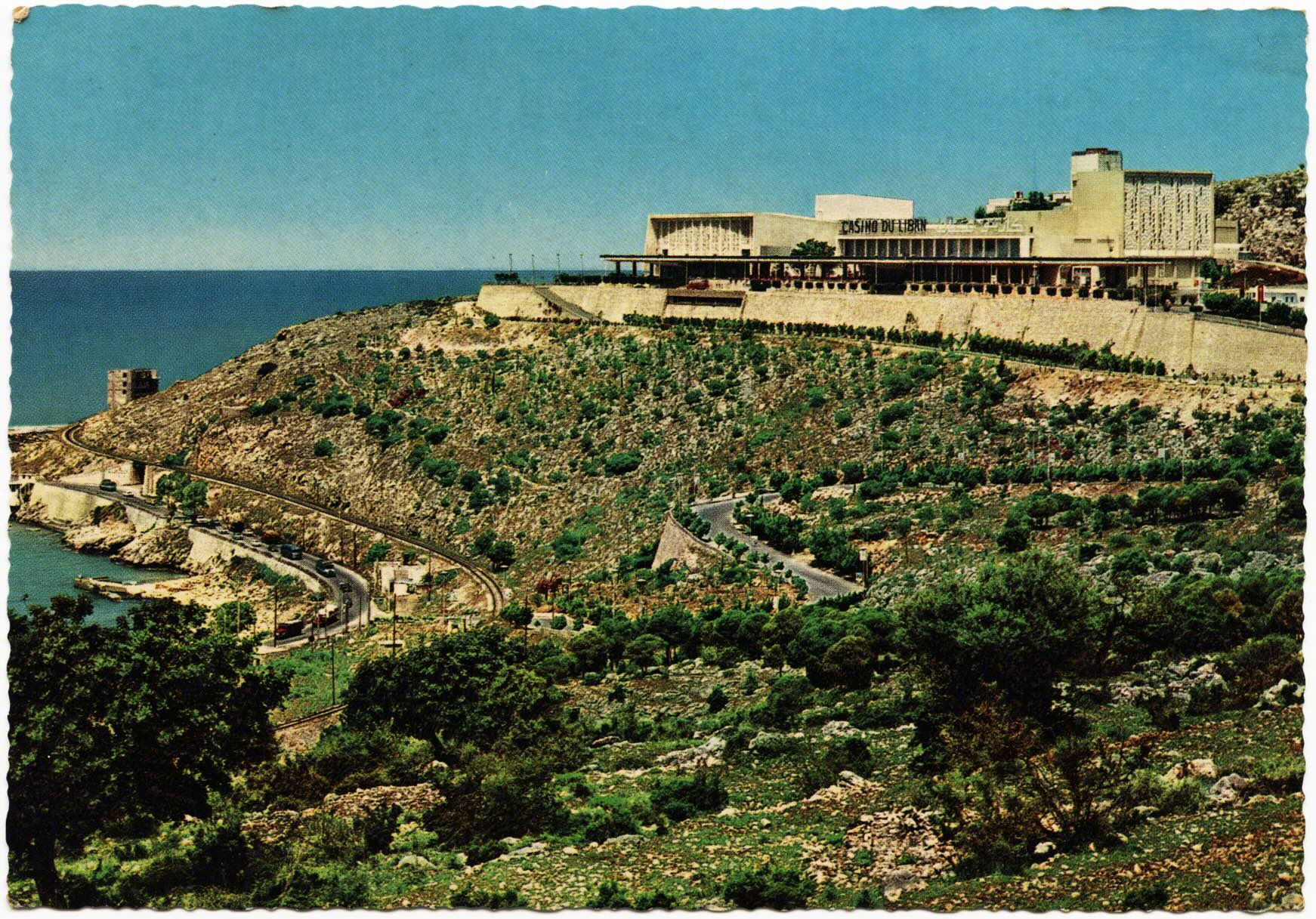

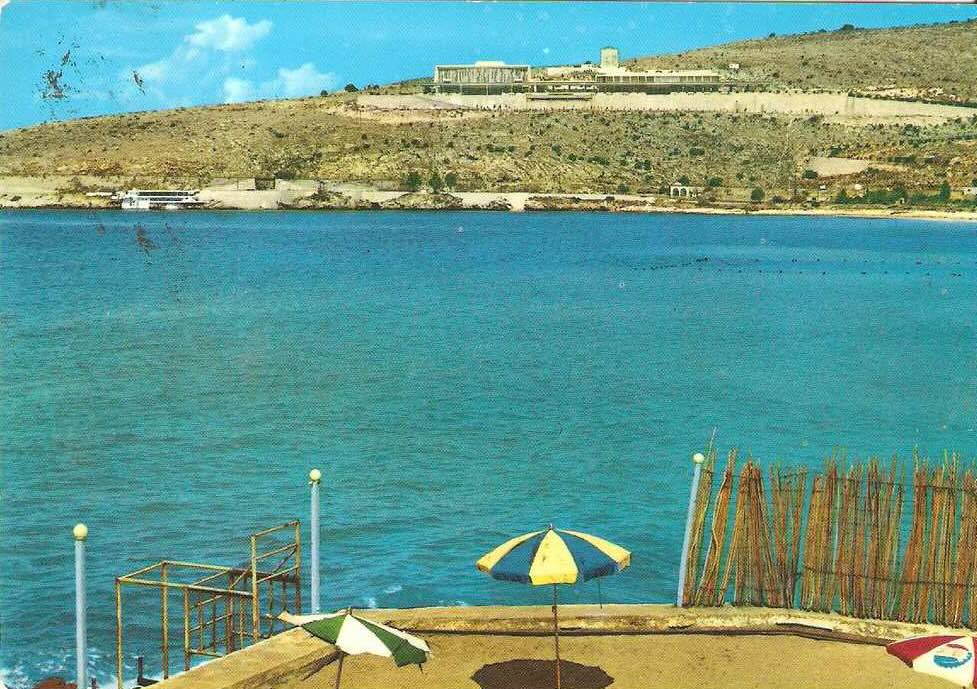

In the fall of 2014 I spoke to a friend in Beirut about this chapter as he looked through a stack of postcards. When he reached this first card he put his finger in the space between the two foregrounded trees, and said: “it’s almost a target, like you can tell the Casino will be there. Even before it was. They knew.” He implied that our eye was drawn to the location even before the site was created. This card was across the bay of Jounieh, below Harissa, and the location beyond the trees would become the famed Casino du Liban.

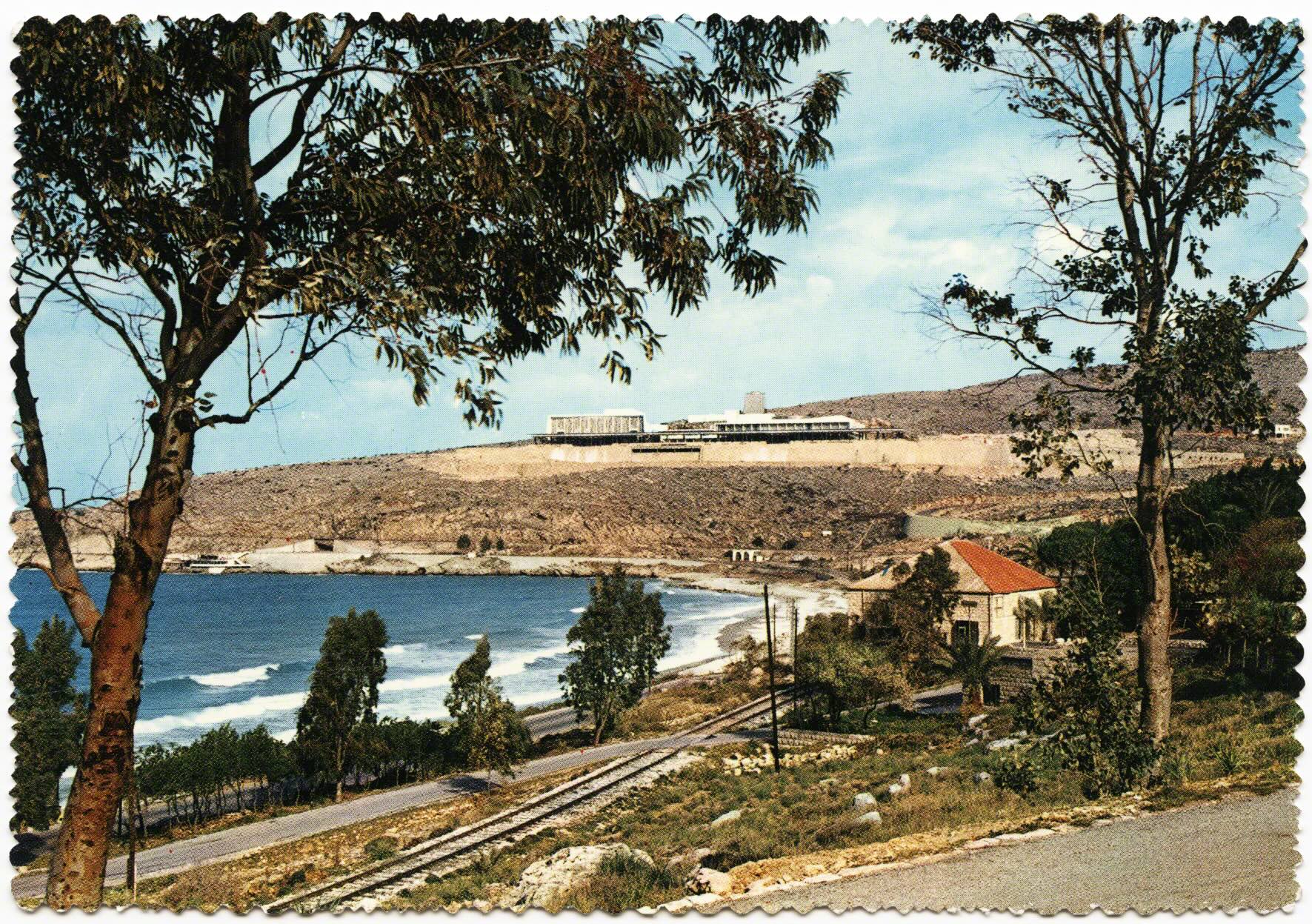

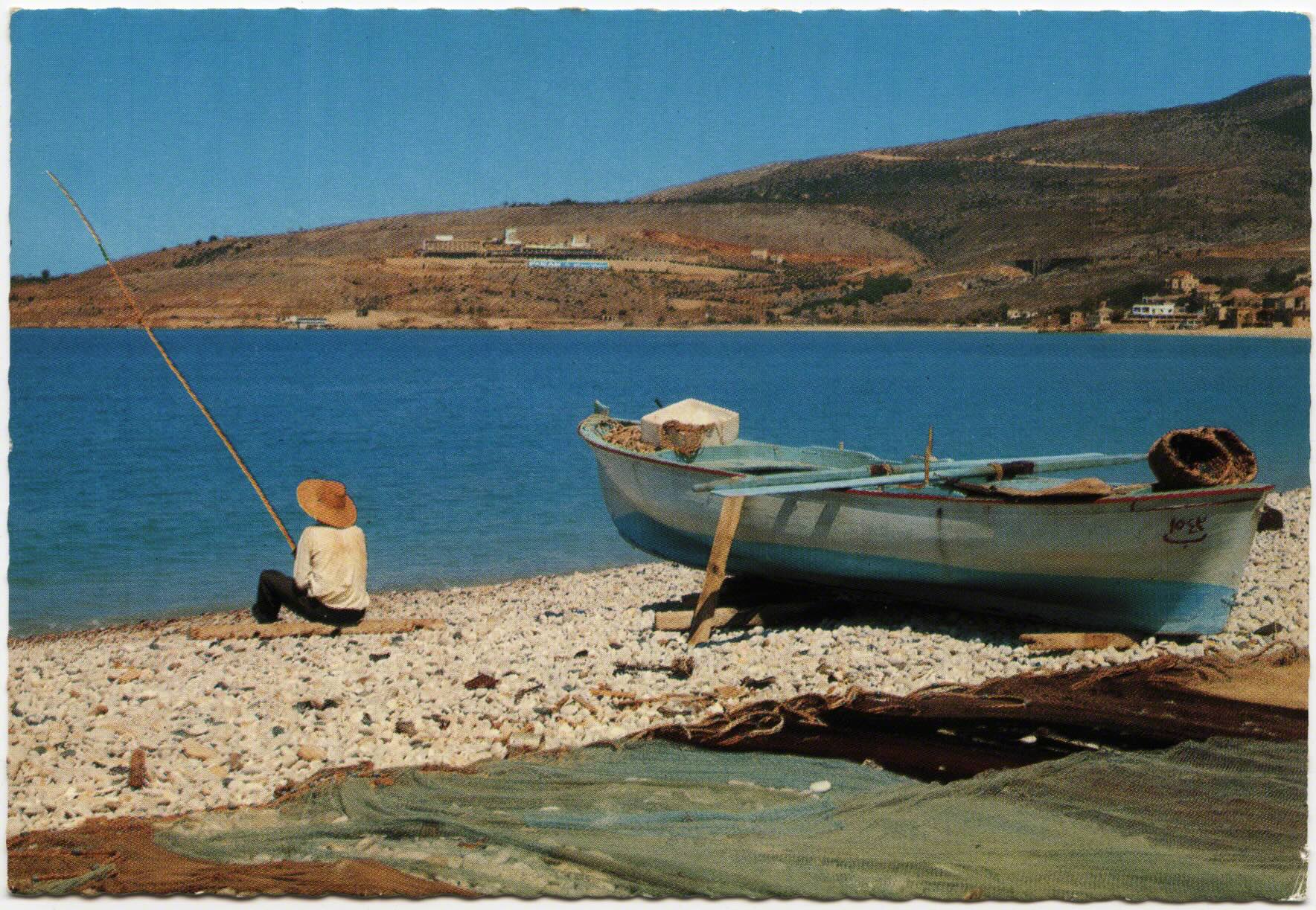

This third flip-book emerges on the face of new mobilities and the age of mass tourism. After Lebanese independence, and from the 1950’s onwards, the tourism industry greatly expanded. There would soon be a large casino and an expansion of beach culture. Given the discussion of the landscape in the previous flipbook, it remains doubly important to consider these interconnections across time and spaces because they illustrate relationships “on the ground they share” (Corner 1996).

An architect described his frustration in 1951 as such: “the lack of good hotels and beach resorts in a place like Junieh is no credit to Lebanon. In fact it is a cause of wonder and surprise that this place be kept so undeveloped” (Ziyadeh: 2). He continues: “this bay is well known to Lebanese citizens, and to the majority of our neighbours, Syrians, Palestinians, etc.” Yet the paradox he voiced was something not specific to Jounieh as his sentiment echoed through out this time period as many seaside enclaves and mountain villages felt that they each deserved more attention, development, and visitors. Ziyadeh stated: “a country like Lebanon, which claims to be in the first place a touristic country, a place like Junieh deserves a hotel” (ibid: 1).

Many plans were developing in Beirut and within a decade huge projects were realized. Ziyadeh noted the problem of passage at Dog River, the bridge which had graced so many postcards and was extolled by the French as engineering prowess, was now a bottleneck. Many investors were waiting for the “new straight-cut 20 meters highway between Beirut and Junieh to replace the existing narrow and meandering road” (ibid:2). This would cut under the inscriptions at Dog River.

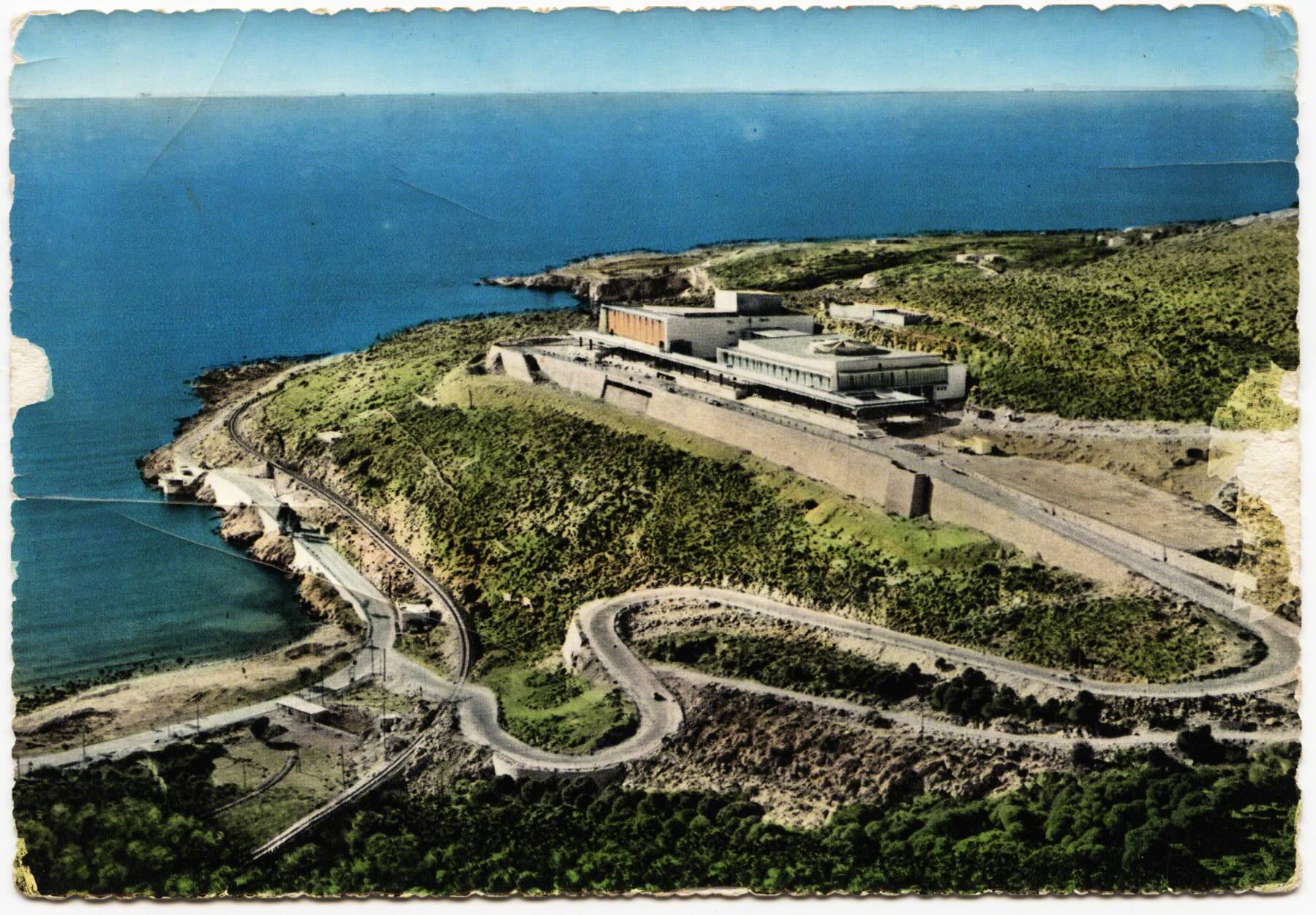

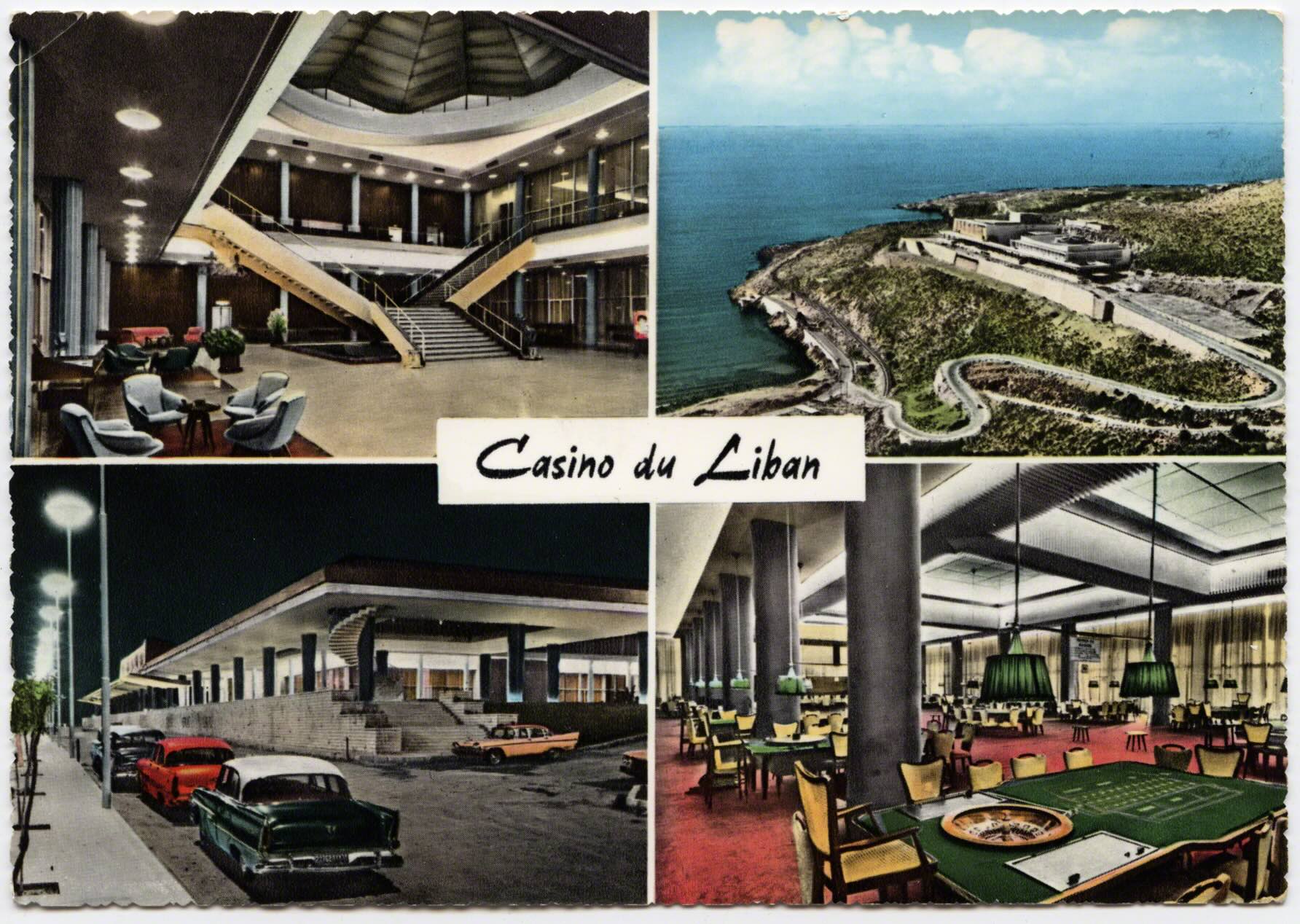

The highway, incidentally, was completed before the casino. The plans for the Casino du Liban were from the early 1950’s and Lebanese president Camille Chamoun wanted to consolidate gambling as well as make a center for tourism. The government issued a decree that allowed official gaming for the Casino Du Liban which opened in 1959. The Casino noted that "Lebanese law (inspired from the French constitution)” selected a non-urban location that was along the coast, “amid 100% natural, untouched beauty." (Casino du Liban 2014:16).

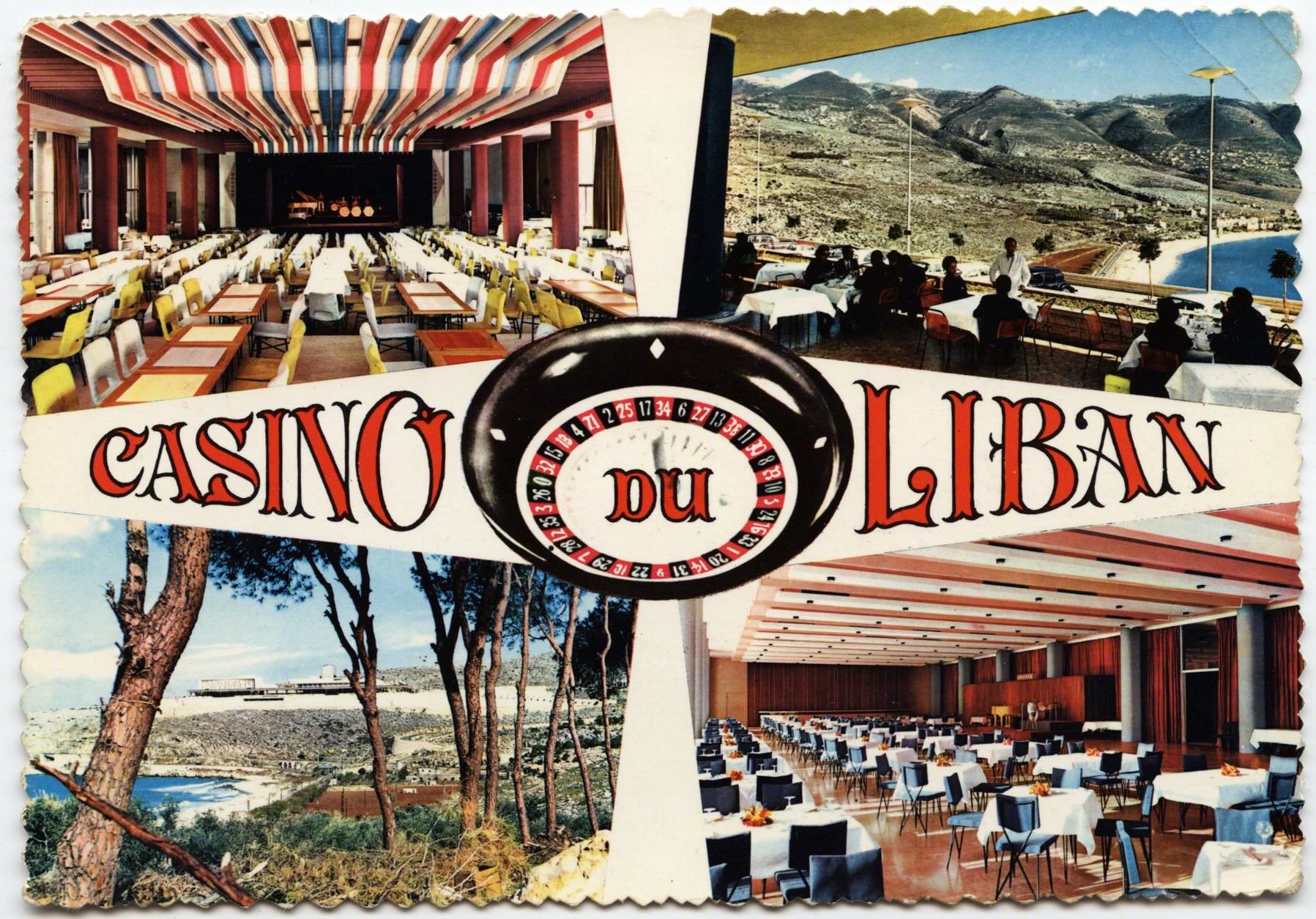

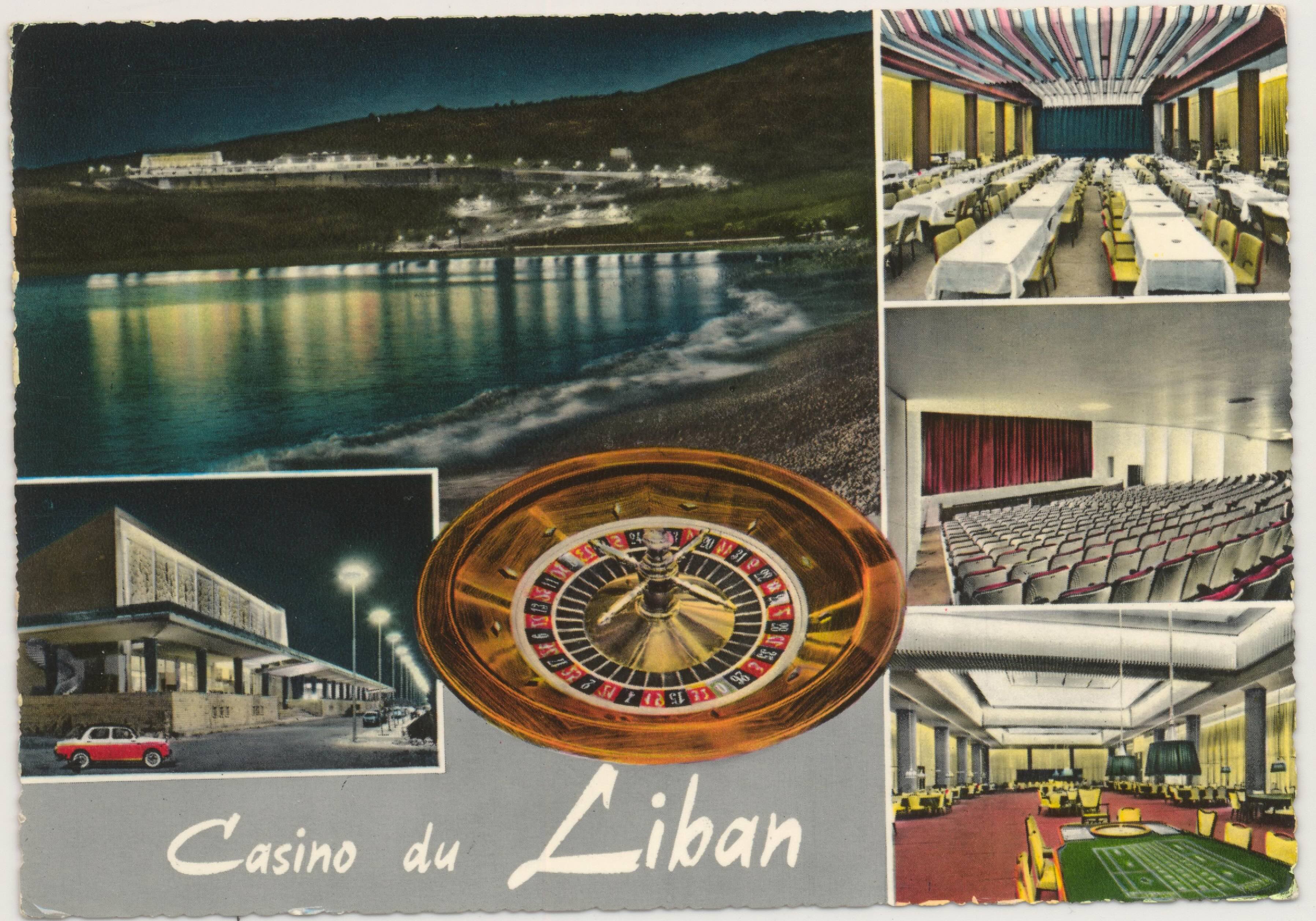

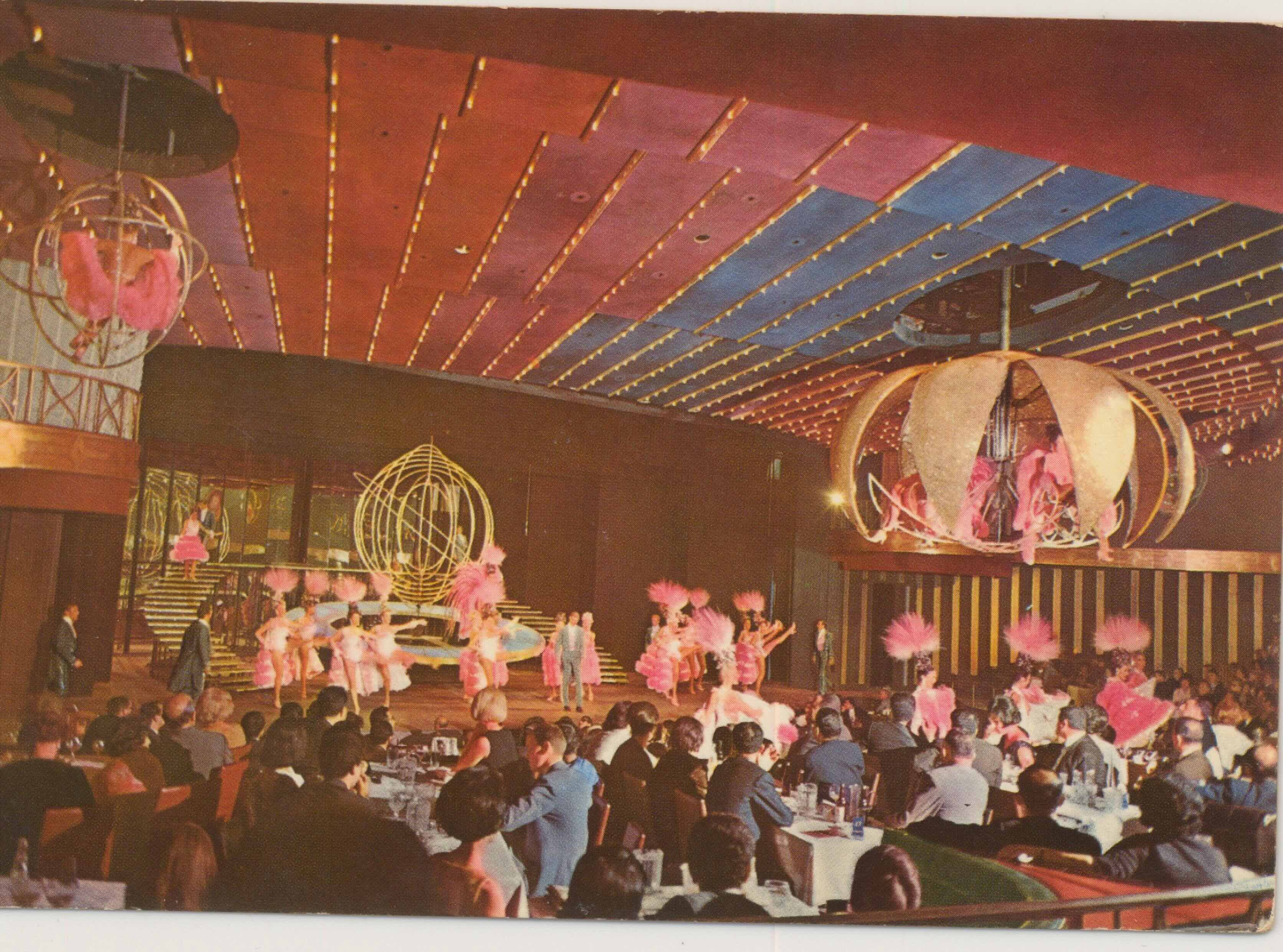

In the publicity around the tourism industry, journalism, and travel logs, the Casino became very well known. More than just gambling it contained an “ultra-modern” theater for 1200 and two restaurants for 2000 people (NAS 1970). The former director of the Casino Victor Mussa said of this time period in the 60’s that “the reputation of [this] small country began to grow and exceed its boarders” (Skaff 1996: 2). Like the mountains becoming a global trope of eras prior, now the Casino (and beach) would become symbols of the nation. The reputation spilled over the boarder and postcards were one means that delivered this message. Clientele flooded the casino as the types of shows, beauty pageants, and concerts increased. In terms of volume in the 60’s, it exceeded that of Monte Carlo and Cannes (Sifakis 1990: 184).

A self-described American hotelier said of the Casino du Liban that it was as “sophisticated” and “rivaled” Las Vegas but with clientele “drawn from the top drawer of Europe and Arabia.” (Venison 2005: 249-250). Another visitor noted that the luxury of this site “mirrored the men who used it" and that the only limitation was “the acres it occupied.” (Atkinson 1973: 63). The Encyclopedia of Gambling from 1990 noted, during this Golden Age of tourism in Lebanon, that the Casino du Liban was the “best, most lavish gambling center” of the entire Middle East and the “crown jewel” of the area during these decades (Sifakis: 184).

As the years passed there were more metaphors used to illustrate the scope and scale of the casino, as well as to frame the broader tourism industry. As nauseating as many of the clichés become, they were powerful ways of imagining relationships. The bay of Jounieh had become the “Monte Carlo of the Middle East” and the “20th century version of the exotic orient” (Takla 1966: 16). The Casino du Liban was said to be the “Las Vegas-in-the-Levant, the biggest and most pretentious thing of its kind anywhere on the Mediterranean shores, not even excepting, in my view, the Casino of Monte Carlo (Clark 1963: 415). And the Eastern Trade Directory called it "one of the most important distraction centers of the world" (Eastern Trade Directory 1968 :119).

If distraction implies diverting one’s focus, then the surface of these cards, as well as the reality of the casino, served as a space of not just distraction, but extraction. The shows of the Casino werefamed. Women were lowered in circular pods which opened, like flowers and elephants marched through the audience (Ellis 1970:251) The casino had the “most striking floor show I have seen anywhere in the world and a huge cast of beautifully dress (or undressed) girls” (Koenigil 1968: 94-95). An airline periodical, showed an image of a dolphin’s head poking out of a wooden crate at the Beirut airport, noted "after entertaining the customers at Beirut's stupendous Casino Du Liban, dolphins are tenderly transported by TMA (Trans Mediterranean Airways) to London." (Esso Air World 1970: 62). So, in addition to the influx of visitors Dolphins were now flown to Beirut for the weekend weekend performances.

Besides animals and flesh, there were endless stories of scandal, spies and sex that emerge from the Casino du Liban. It was in numerous films which always focused on espionage and danger just as Lebanon was imaged (and in practice though residual colonial and imperial interests) a juncture between East and West. Others stood by their comparison to the brand of films, noting it was a “real backdrop to a James Bond novel” (Venison 2005: 250).

In what ways does visual imagery fold back into the growing narrative of the Lebanese tourism industry as excessive, permissive, extravagant, and luxurious? Tilley notes in the work of De Certeau (1984) the spatial practice of stories and narratives and here the postcards function as a “discursive articulation of a spatializing practice” (Tilley 1994: XX). While the casino was on Lebanese soil, like other parts of my work (namely on Hotels in Beirut and Summering villages in the mountains), these spaces were predominantly for foreigners and rich Lebanese – the casino “lured the jet-setters, Greek shipping tycoons, oil sheiks (Sifakis 1990: 184). It was “a marble and glass palace…East meets West once more as tall blonde Scandinavian chorines stage performances that rival those of the Lido while Arabs play baccarat and American oilfield workers shoot craps.” (Smith 1965).

It was this increasing contrast of nationalities, wealth, and seeming discrepancies of what produced much excitement. These narratives of the Casino were mirrored in the air that filled the tourism balloon: half hype + half hope. Year after year getting bigger, and despite being blown around in the winds of conflict in the 50/60’s, the balloon kept sailing higher, bigger. Did it float too high loosing sight of the ground, of the citizens and landscape from where it came? A recent memoir from two Lebanese brothers noted that Lebanese could sometime have problems accessing the Casino. At some point, in their experiences, Lebanese were prohibited "from entering the gambling rooms, but if you owned a few properties and were approved by the Treasury Department, then no problem." (Mechawar & Mechawar 2013: 254). This similar exclusionary spatializing practice would be one that emerged with full force in the tourism industry, which hints to how, and under what circumstances, people were privileged, invited or welcomed.

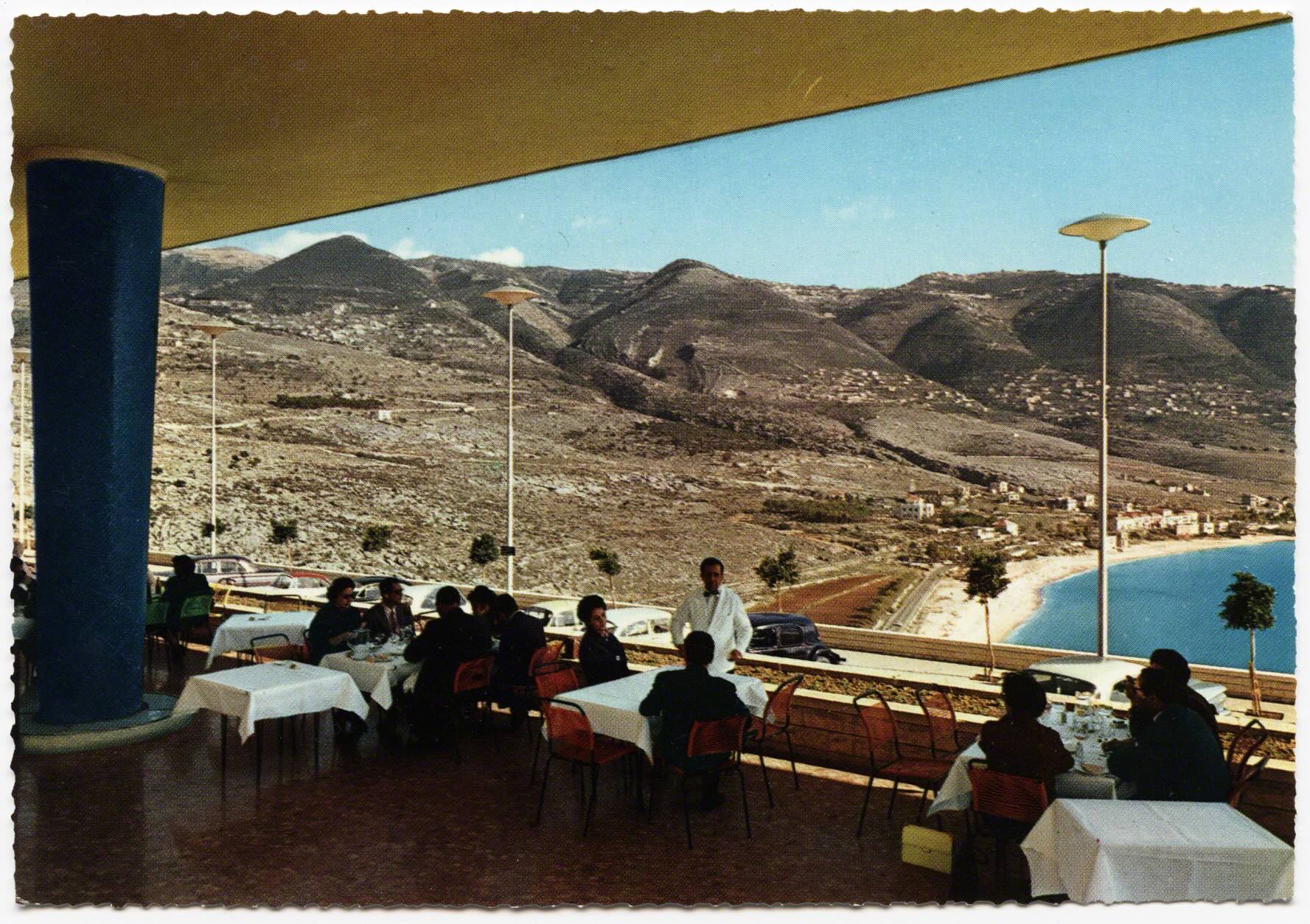

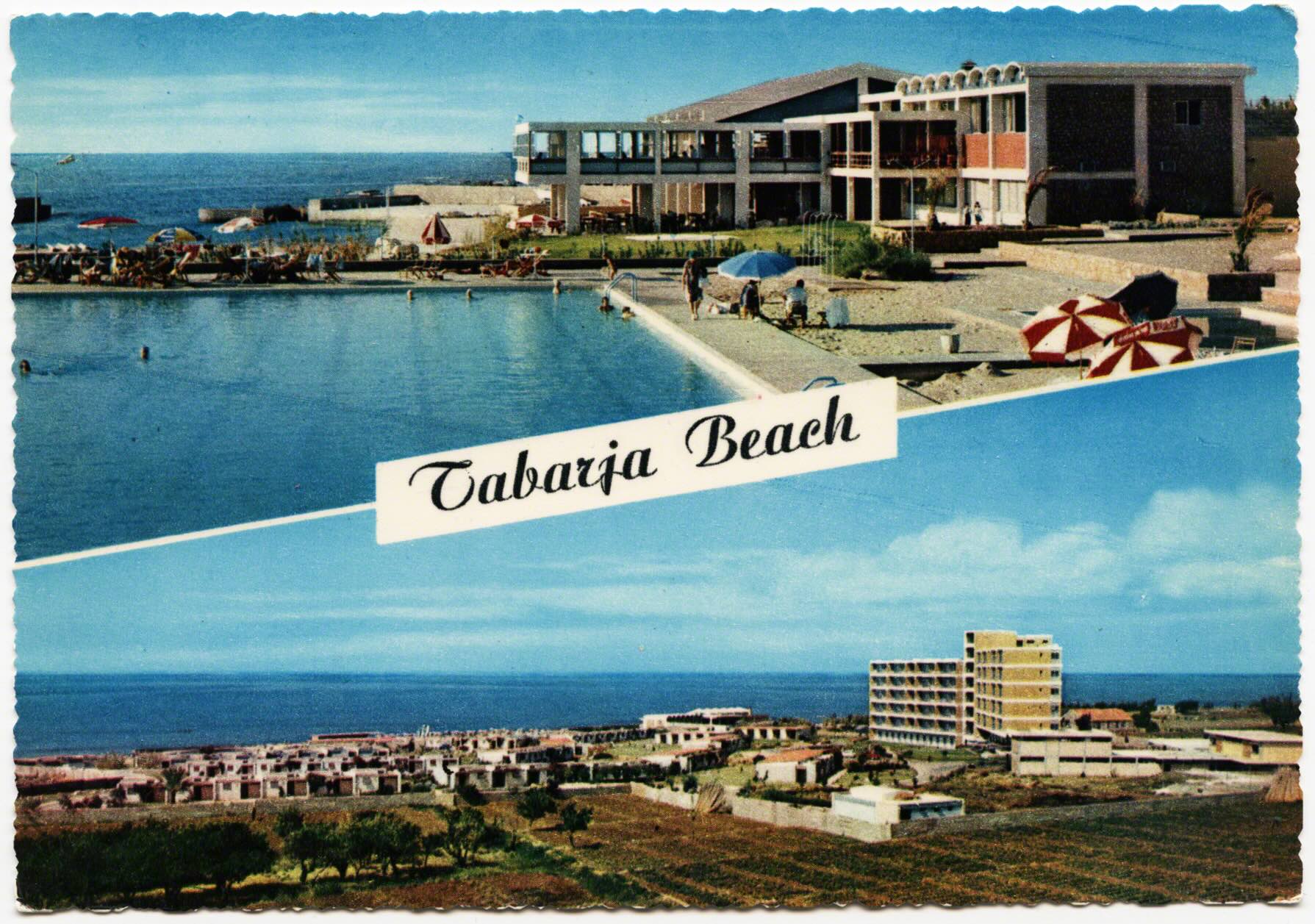

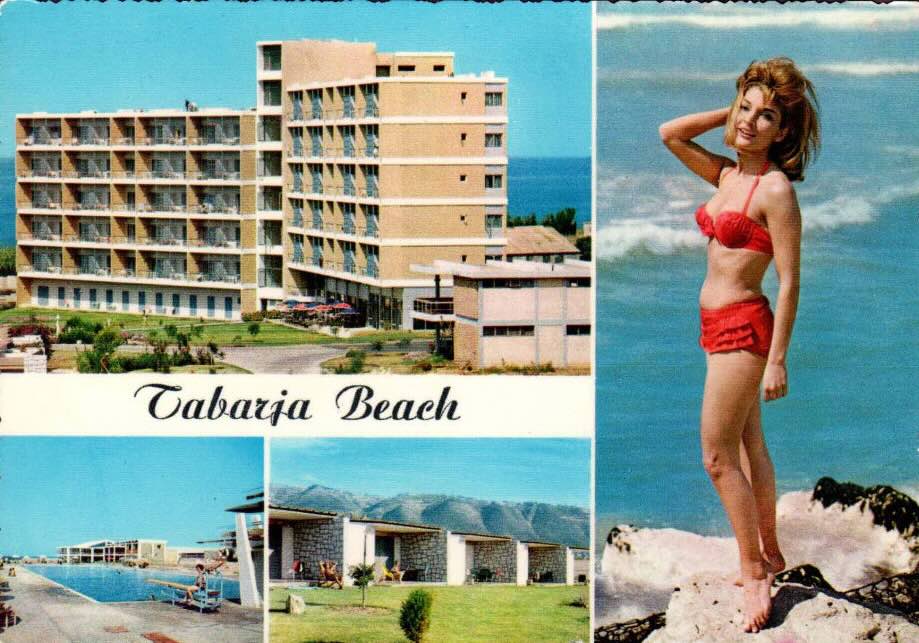

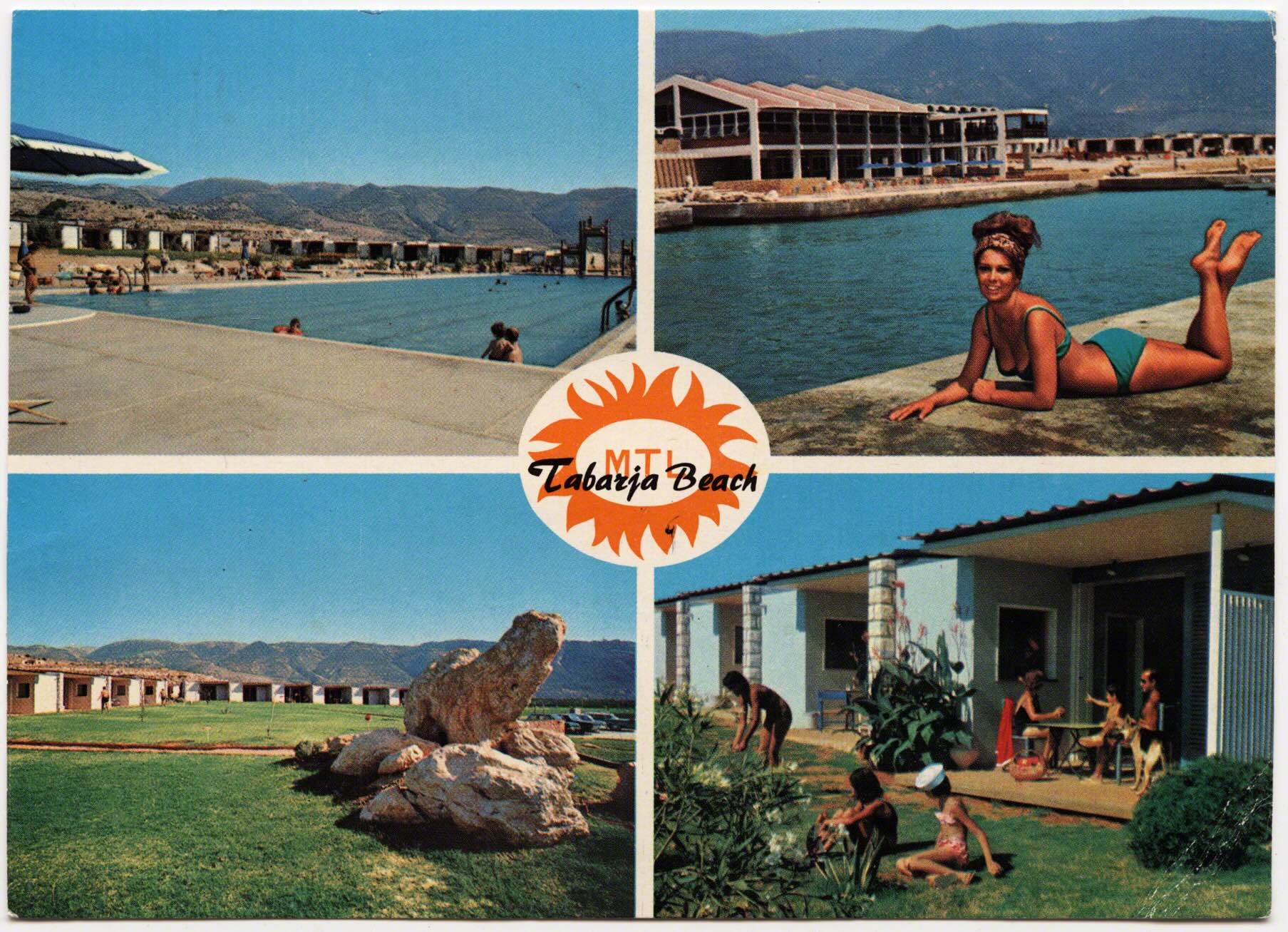

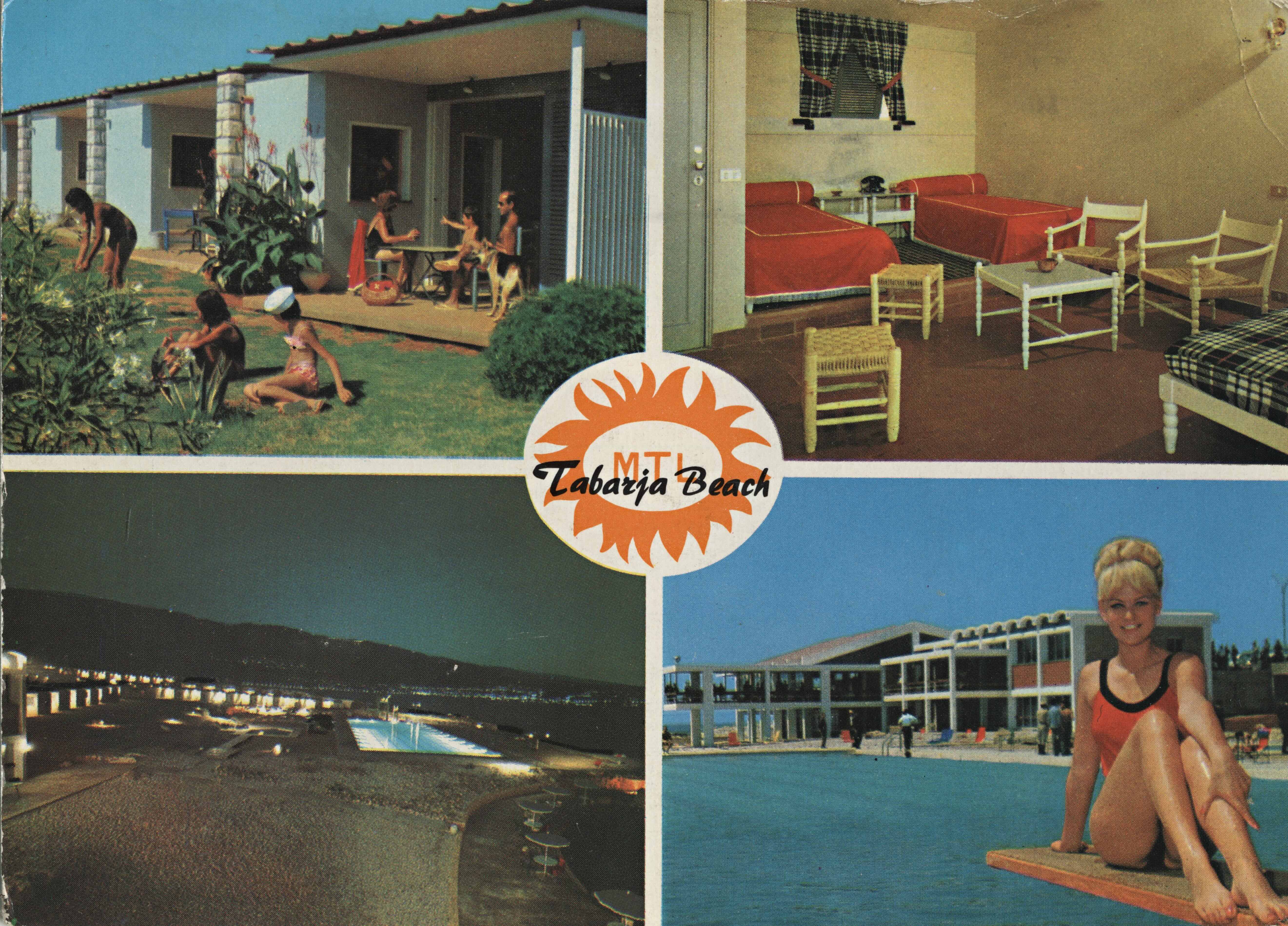

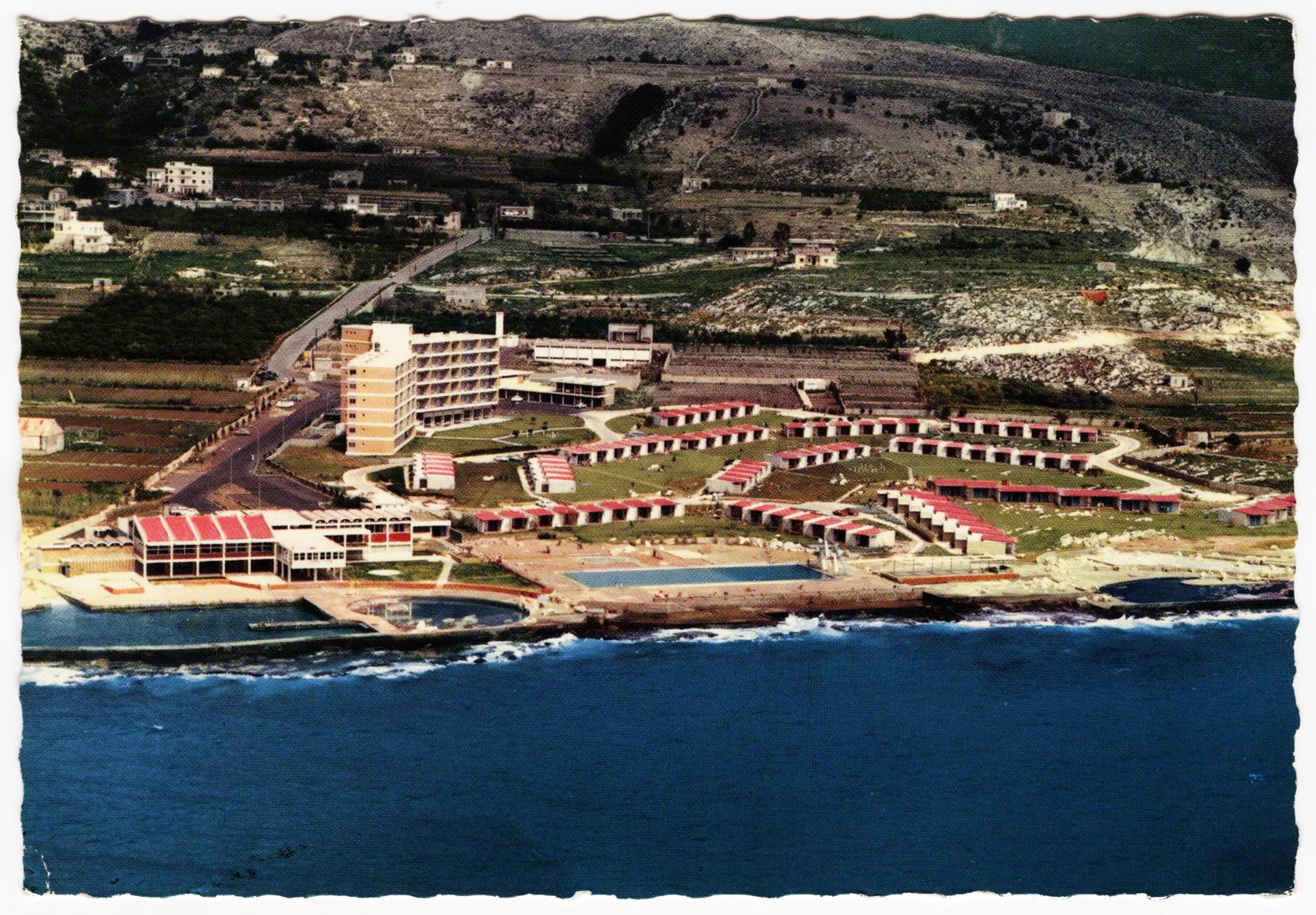

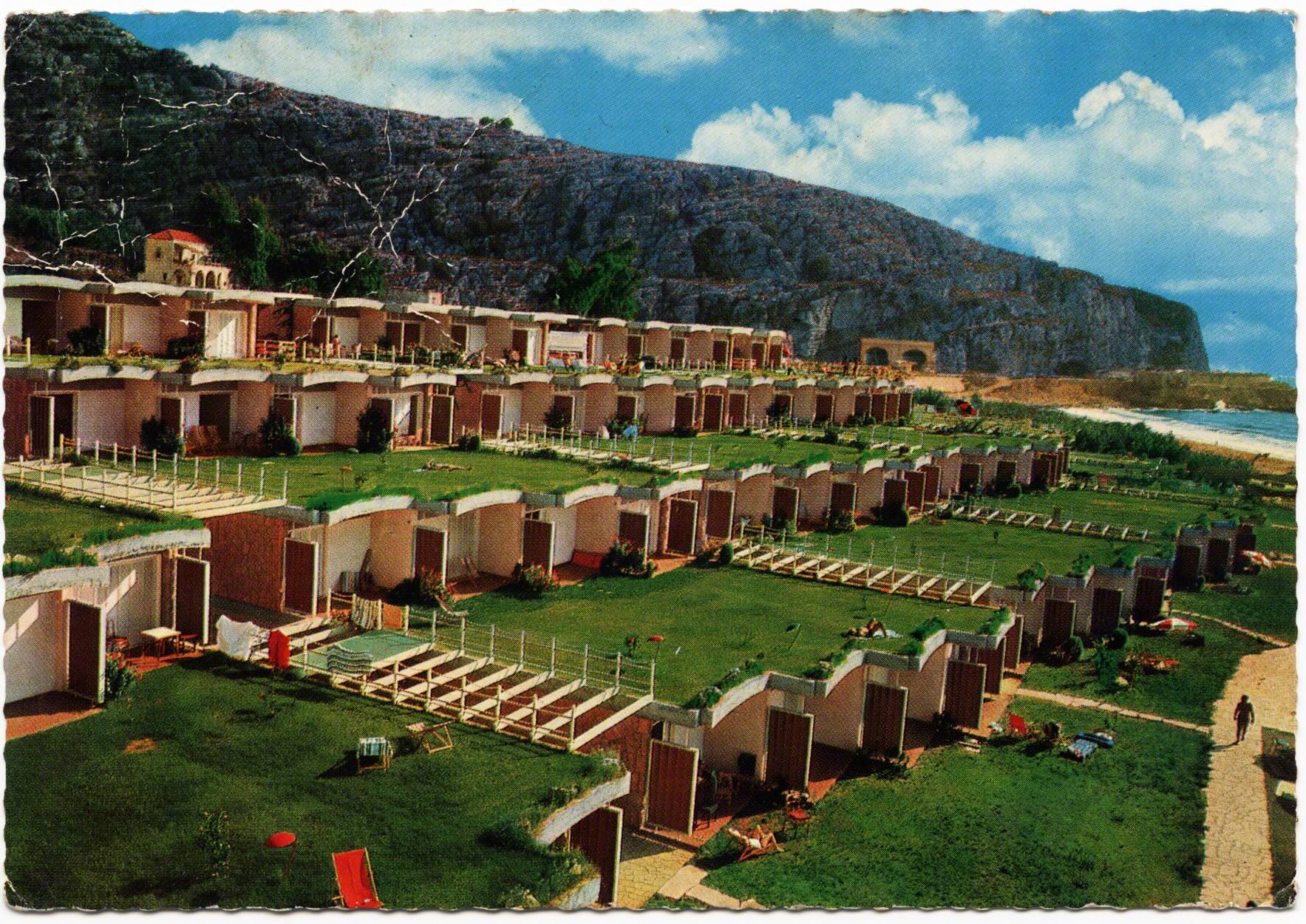

At this same time the casino developed, so did the coastline. Below the casino as the bay curves there was a small village named Tabarja, where St. Paul was said to have set sail to Europe (Rowbotham 2010). By the early 1950s many beach resorts were opening across Lebanon, which expanded conceptions of the summertime and a large beach resort opened called Tabarja Beach.

Americans and Europeans were one target in expanding tourism in the 1960’s as Gulf Arabs continued to stay in the mountains in the summer. “Among developments designed largely for the American trade is the new Tabarja Beach Hotel north of Beirut, building facilities for 400 guests with an Olympic-sized pool and a yacht basin” (Kanner 1965: 149). One travel periodical from NewYork described it as a “new luxurious resort near Beirut…bungalows with private gardens, music, refrigerators, may be hired by the day for $14.00 each." (Travel 1964: 15). Kim Philly even picnicked, and drank, here before leaving Lebanon (Seale & McConville 1978: 303).

By the mid 1960s Jounieh has a strongreputation as a “summer” spot in the spine of Lebanon’s coastal developments. Saudi Aramco promoted it as the “most lustrous jewel in the chain of coastal resorts that have won Lebanon the apt title, ‘Riviera of the Middle East’” and “jewel of Lebanon” (Tracy 1968: 22?) . The PanAm Guide for American’s Living Abroad noted that one could rent a summer beach chalet for $490-$1,145 at Tabarja Beach (Pierce 1965: 263). These spatializing practices, realized through the market, already show a preference for foreigners and only those Lebanese that had enough money to afford access.

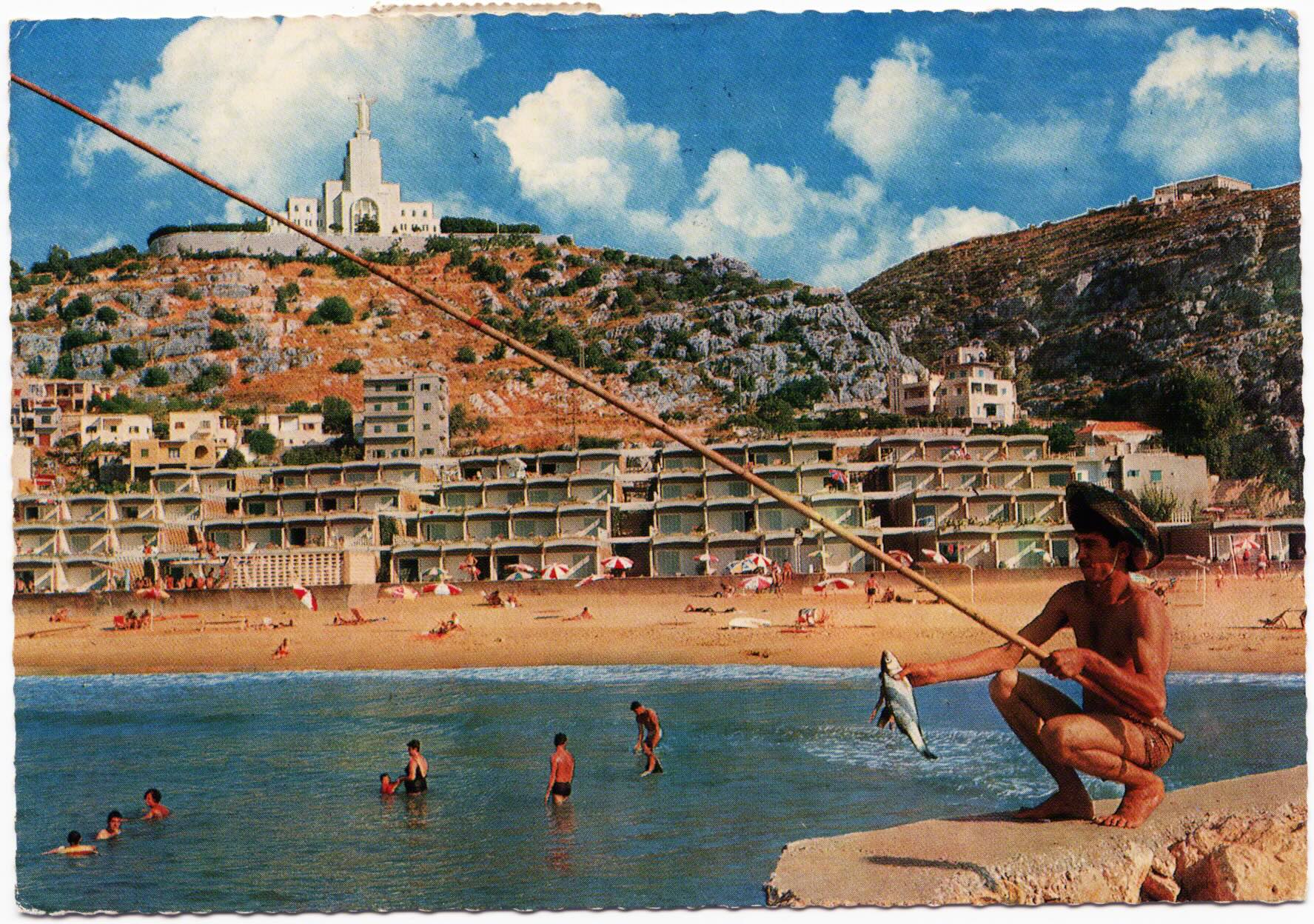

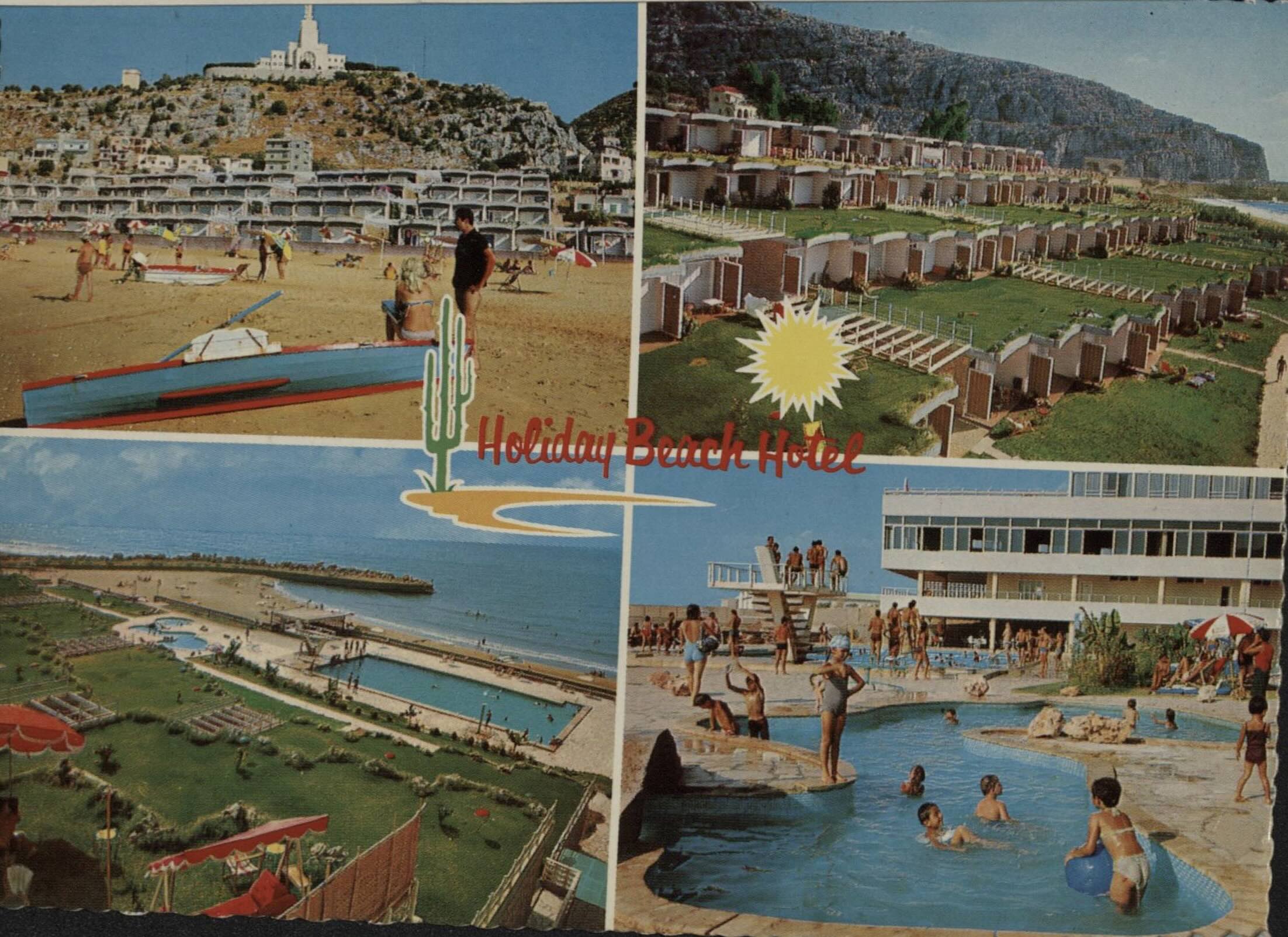

As in the previous flip book, we returned back to Dog River for a twin development. There was a beach lesiure project that mirrored Tabarja Beach, on the Northern side of the river, below Jesus the King. When Holiday Beach was established it was not as luxurious as Tabarja, but it became well known. These postcards show a view that one might see swiming in the mouth of Dog River, under the gaze and embrace of the marble effigy.

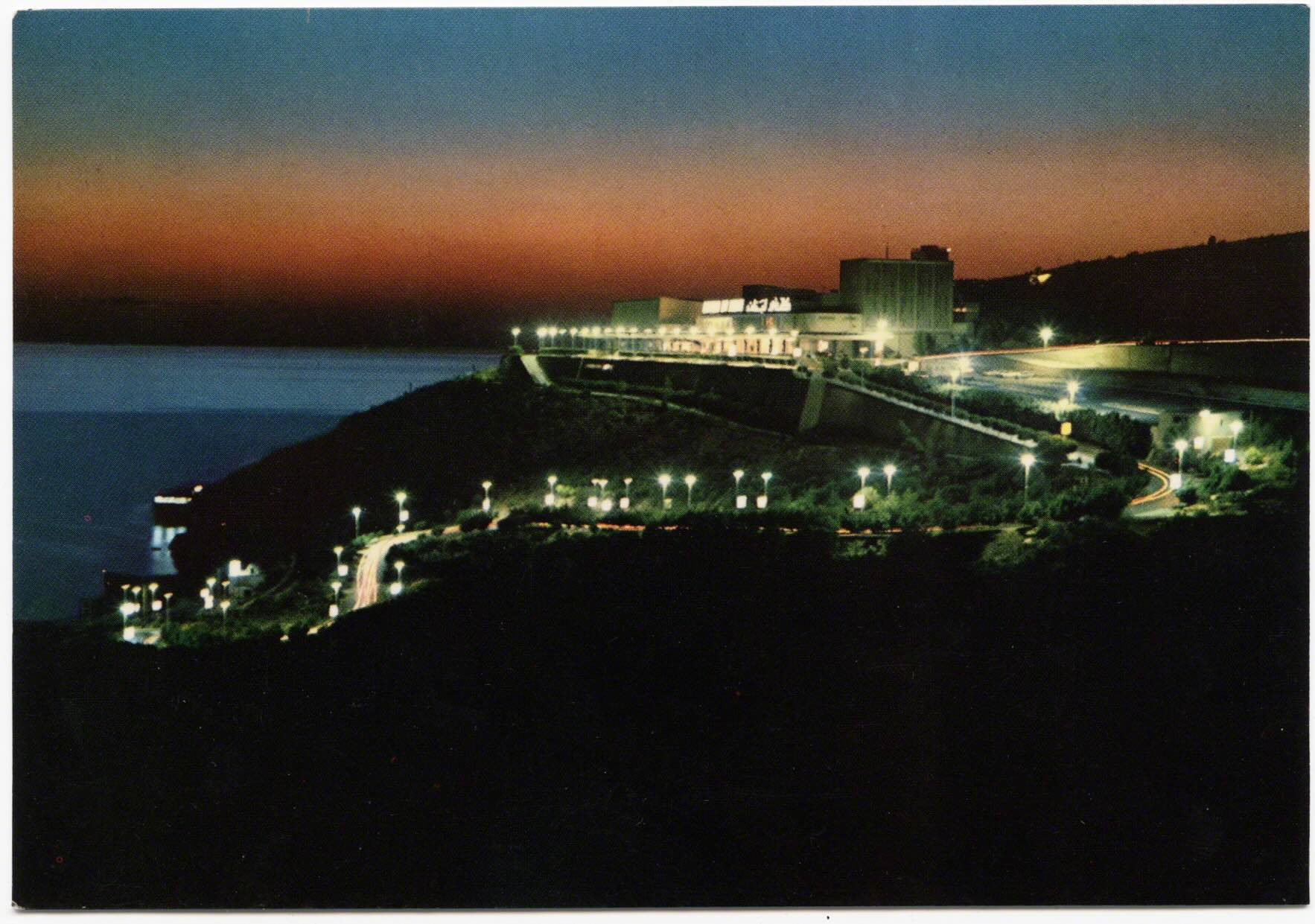

By this point the medium of postcards were meant to condense in order to project a certain perspective. A “snapshot” of meaning - capsule - glance - moment - hope - desire. During this era postcards were more directly linked to the establishment, and bolstering, of the tourism economy. Often these cards were produced by the entrepreneurs and actors who would directly profit off of their circulation (such as hotels).

In this way, the “surface” of these images is glossier, shinier. This sheen doesn’t hope to capture an essence as previous decades’ postcards might have, but hopes to foster and cultivate one. The reflective power in these postcards frame an aspirational future, and I posit, one that is more fun, extravagant, and sensual. In this age of mass tourism so too does imagery become mass produced and consumed. The tourism industry becomes more linked to visuality, the camera, and changing public relations driven by investments and profits.

While the discussion of postcards began by thinking how they can stand as a metonym for travel and mobility, by this point in Lebanon they represent a “metonymic fallacy” for the nation (see Barthes 1975: 161-162). The tourism industry, and what it represented, I would argue, was often taken to be the referent and stand-in for the nation. As if these surfaces were representative of Lebanon, when these flipbooks are eddies of tourism. Traps not paths. This fallacy was enhanced by visuals, photography, postcards, stamps (etc.). Many of the postcards also used techniques to encase and envelop the viewer in an eidetic frame of reality. Through the coloring of the photographic negative (like an Instagram filter), the framing of the waves, the smile, or how they draw the viewer into them. The genre of montage becomes popular, which is only telling in so far as the types of views that become assembled on the card indicate an eddy in which one’s body and view is stuck.

In this time of increasing masses: mass-tourism, mass-mobility, mass-consumption, mass-imagery, we are reminded of Kracauer’s ornament (1929). He noted that the masses produce a form and structure through these ornaments which reveal "the aesthetic reflex of the rationality to which the prevailing economic system aspires.” Postcards were aspirational but these surfaces reproduced values of the capitalism production in which tourism was trapped. Tourism was folded into public relations and became a main artery of the national economy.

Guy Debord building on Kracauer’s work proposed “spectacles” as a modern version of the ornament (1987). Debord explores the relationship between visual culture and commercial interests where "spectacle obliterates the boundaries between self and world...here surface exceeds its frame and consumes the world around it” (Debord 1987: 221). Thus, the mass spectacle of tourism, and postcards, interpolated the Lebanese, as well as the world. As such, these postcards are little more than caricatures of place which resembled it in likeness, a simulacrum, but were actually an “extravaganza of undifferentiated surfaces” (Baudrillard 1989: 125). As such, they are surfaces of surfaces.