=========

I Postcards:

Place, Photography & History

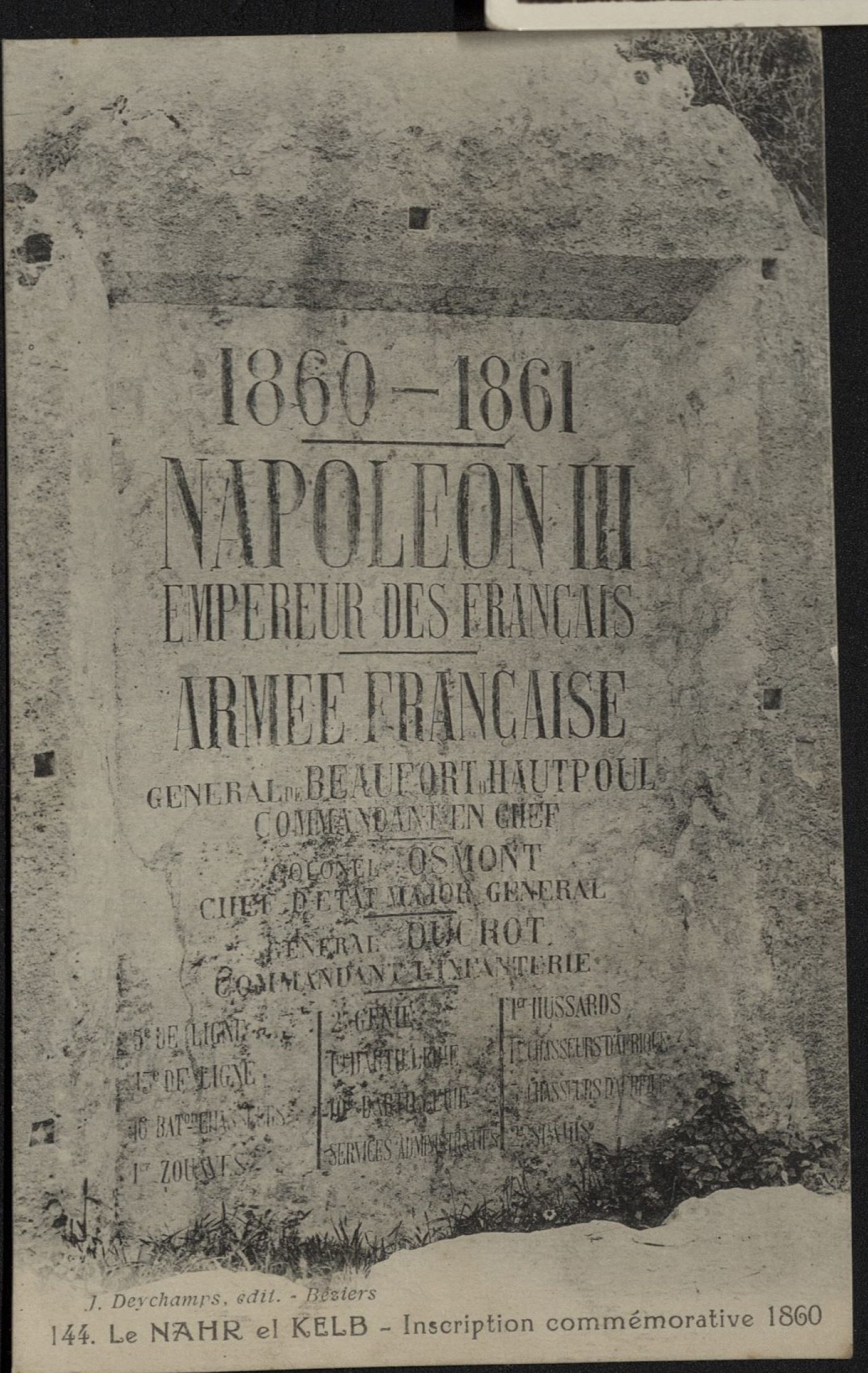

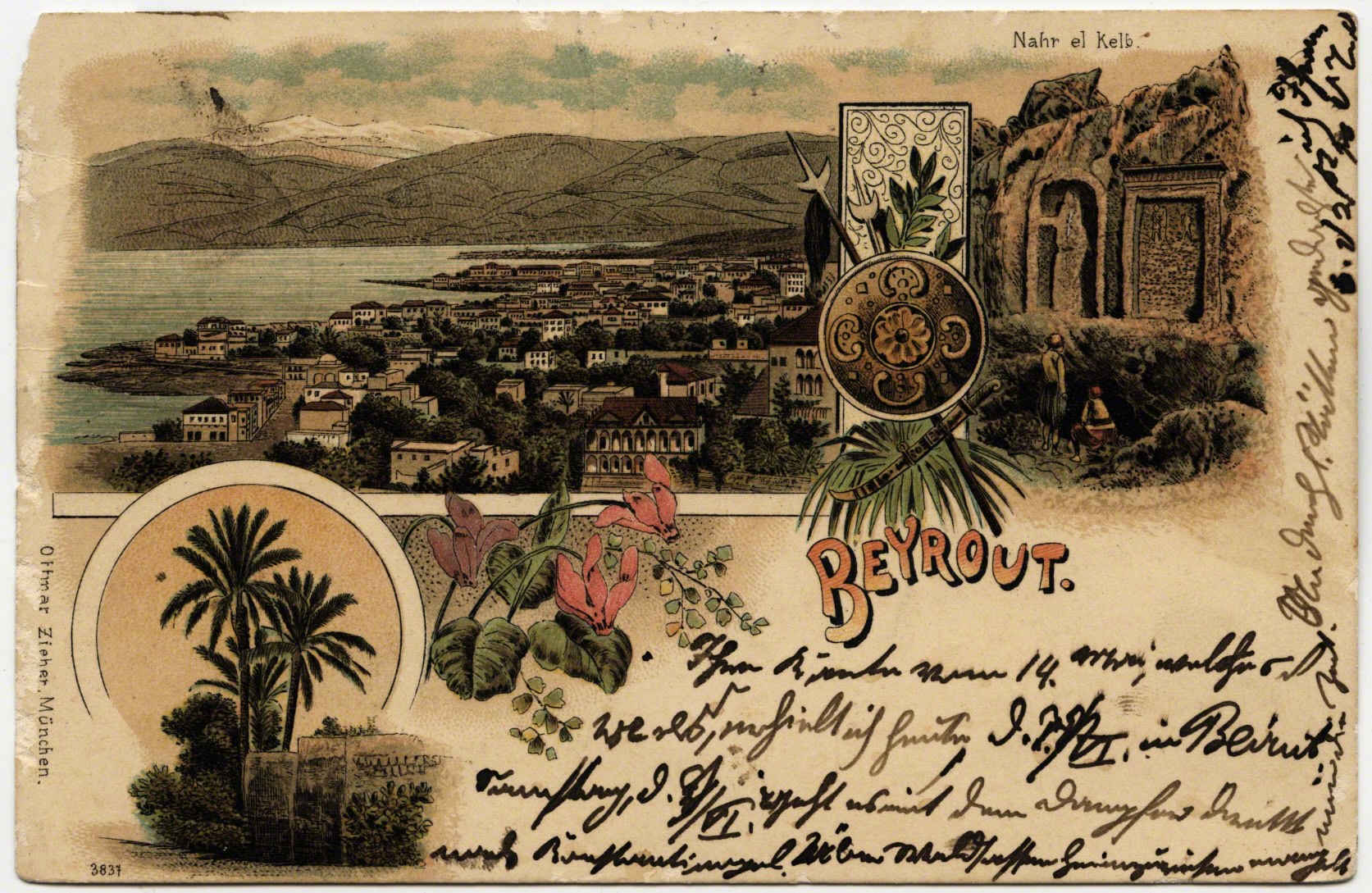

Roughly 12km outside of Beirut is a commemorative plaque on the side of a hill placed by Napoleon III and his army in the year 1860/61. Today it rests at street level almost kissing asphalt off an exit ramp of the main highway running north to Tripoli. Given his reputation, it might come as little surprise that Napoleon mounted the memorial of his passage through Lebanon directly over an inscription from Pharaoh Ramesses II from Egypt, carved in 1271BC.

Napoleon’s act of one-upmanship concealed the previous conqueror, but there are 21 other inscriptions, carvings, and plaques that dot the limestone rock face at the mouth of Dog River (نهر الكلب) This location forms a visual and imaginative marker of mobility, passing armies, imperial and colonial projects, and the making of the Lebanese state through tourism. As such, it represents a site of commemoration realized though a collection of inscriptions on the landscape (see Volk 2012, 2008). Many legacies and events are memorialized in stone.

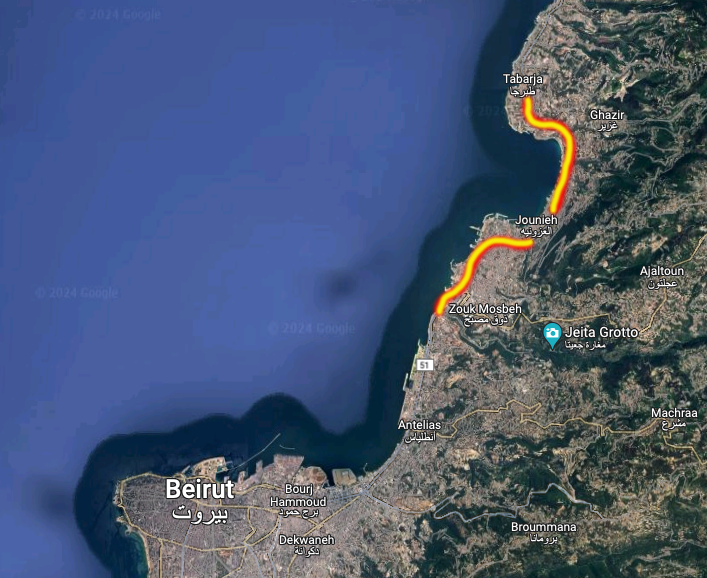

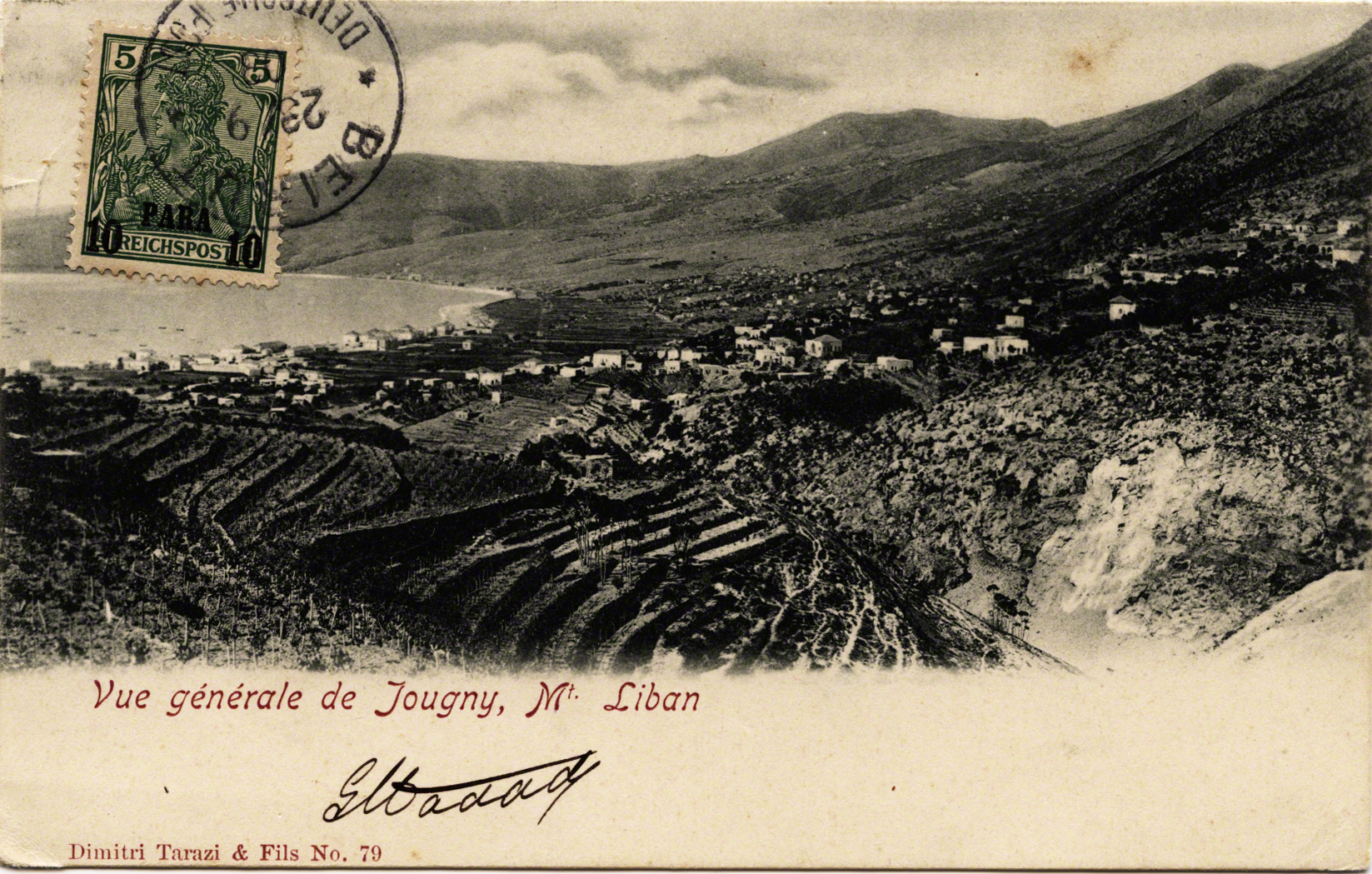

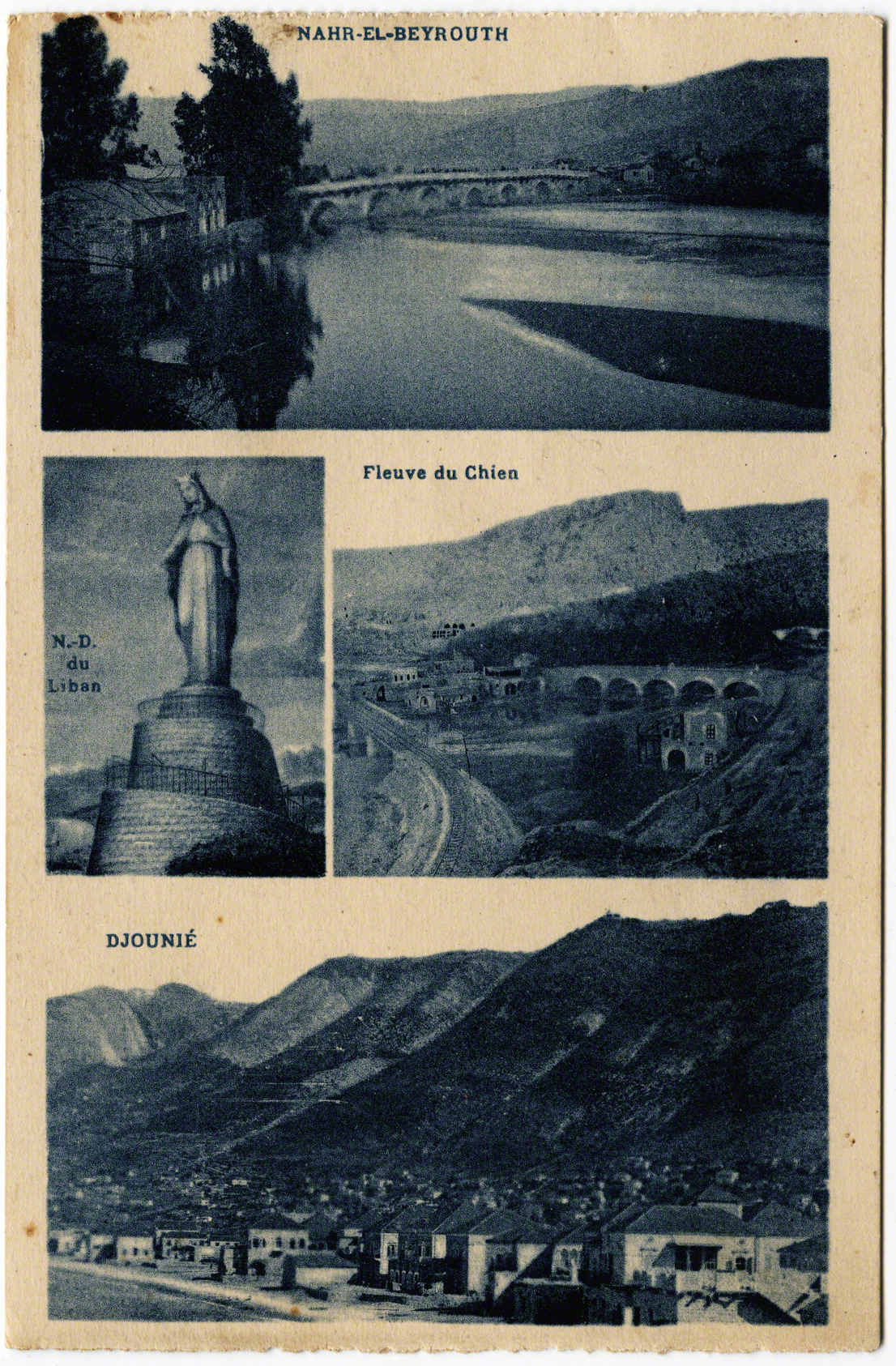

This piece situates the context and regional importance of postcards in Lebanon to think through progressing visualizations of place. The views presented here span a small 7KM strip of land from Dog River through the bay of Jounieh. The sights on these postcards signal changing occupations, modes of consumption and movement, and the development of the modern nation state of Lebanon. They offer some 7-km-glimpse into an 80 year span of postcards.

Inspired by the work of Arreola on the border between Texas and Mexico, there is a “serial scripting” that happens by juxtaposing multiple views of place in time (2013). To do this through postcards then creates an “assembled view of places, spaces, and monuments, that become worth noting - while others fade away” (ibid - my emphasis).

This analysis will also explore the “surface” of the image as inspired by the work of Kracauer (1929). I am combining these two terms to think through these postcards in a serial surfacing. The scripting proposes a sequence to view the images while surface highlights the printed form and materiality, surface of the nation in the land, and surface linked to the indexicality of what they projected.

As I will argue, these postcards do not serve strictly as an archive of moments, but were part of an evolving and changing landscape of meaning and mobility to/through Lebanon. They create views of locations which are permanent, unlike the actual landscape, and do so onto a representation that is mobile – and meant to be a mobile representation of it. As such, these postcards created a triangulation between place, image and viewer.

This piece begins by briefly considering the medium of postcards and photography in the regional context of Lebanon. What follows are (3) image based “actors” that emerge. Each from the within this 7km strip of coastline. These actors are created through a series of images that fold on top of one another, in progression, like flipbooks through views and times. They create movement and directionality in space/time because “places are always unfished, deferred and lacking a unity or order established through representation” (Hetherington 1997: 187). The hey-day of postcards was a time when photography exploded and technological advances delivered bodies, ideas, and things around the world more quickly. Thus postcards too were built onto, and represent, these circuits of mobility. Important questions concerning modes of production, local photographers, publishers, colonial agents, individual postcard messages, and the various publics meant to consume such images are salient - but largely outside the scope of this analysis.

An analysis of postcards is not just to conjuror trivial visions of the “past” or raise nostalgia. As images they are performative flashes which render certain views of place visible, frozen, but index a changing nation, reveal power relations, and often typify through their views. The perspectives they present creates a “unique vision because often the same locations and landmarks get photographed and reproduced generation after generation, enabling a sequential perspective through time.” (Arreola 2013: xv).

What developed across decades were eddies of locations in which bodies and visions were stuck. These images do not attempt to recuperate the history of these times, but through a visual progression, in the material medium of postcards, this analysis explores how place was represented and constituted through tourism and movement. Through this the three actors emerge: a river, a virgin, and a casino.

After WWII, and in the ensuing age of mass-tourism, postcards became intrinsically tied with “tourism” and encapsulated a view/idea/vista/stereotype of a place. Yet, what is the role of this imagery, through the sub-genre of postcards as time passes? How do these images, once released, contribute to imaginations of a place as they circulate and move? Or as they hold of view of something lost, another time? I ask the reader to think of each postcard as a drop of water. Droplets fallen from the sky that might collect, flows, conjoin, and gain momentum. Perhaps they run down the landscape over existing channels and carve new paths through stone. Might they be part of what forms a river of our thoughts? Origins and destination are blurred.

=========

II Surface of a River

Departing Beirut, heading north to the bay of Jounieh, one must first pass over “Dog River.” Many years ago, before I knew the significance of this location, a Lebanese friend recounted how his grandfather had explained the river’s unique name when he was a child. He was told that a protective dog guarded the mouth of the valley on the banks of the river long ago. One day a traveler passed and killed the barking dog for being territorial. The traveler continued on his way across the river. My friend then noted that to this day, once a year every spring, the river runs “red with blood,” which proved that it was the dog’s river.

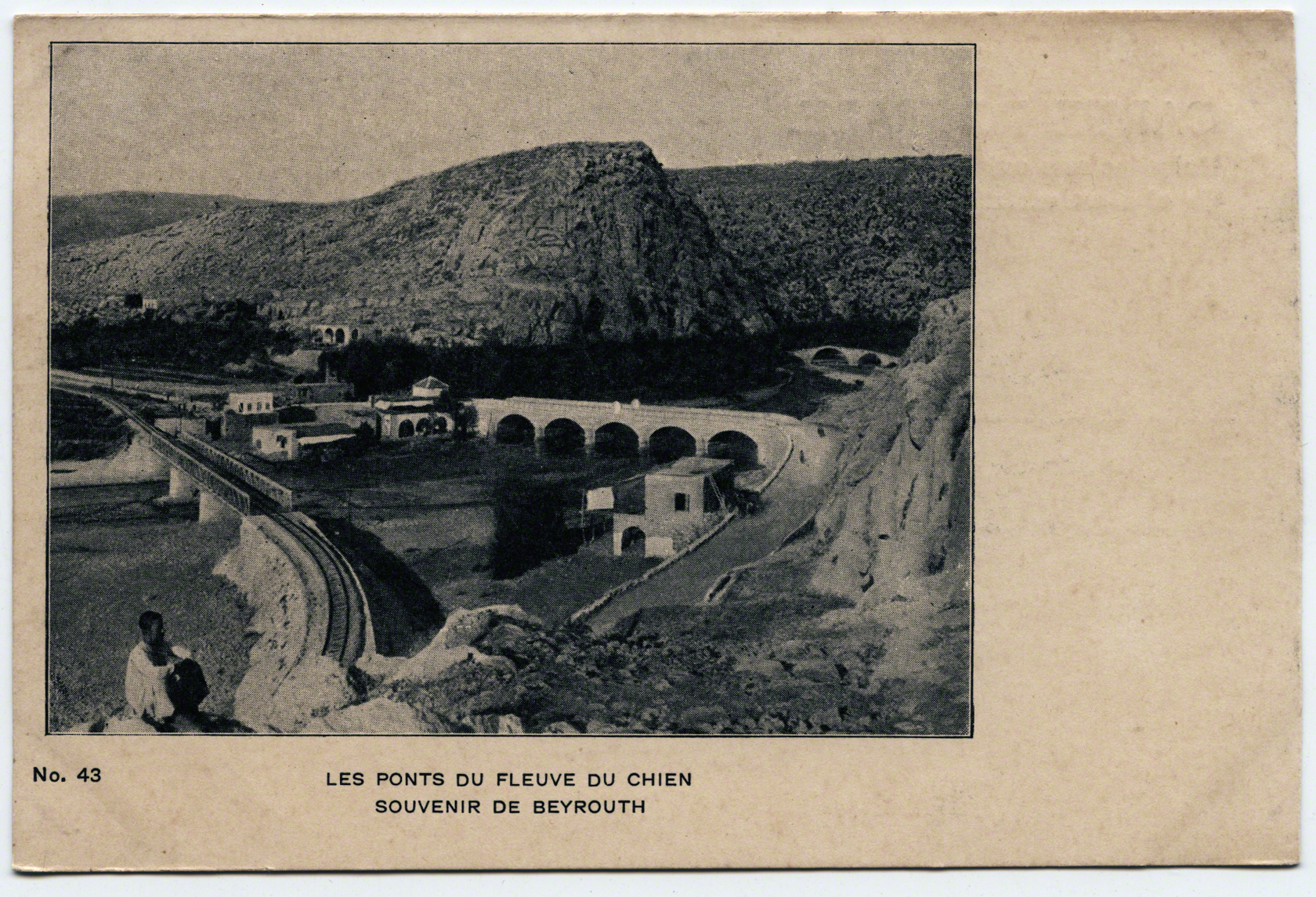

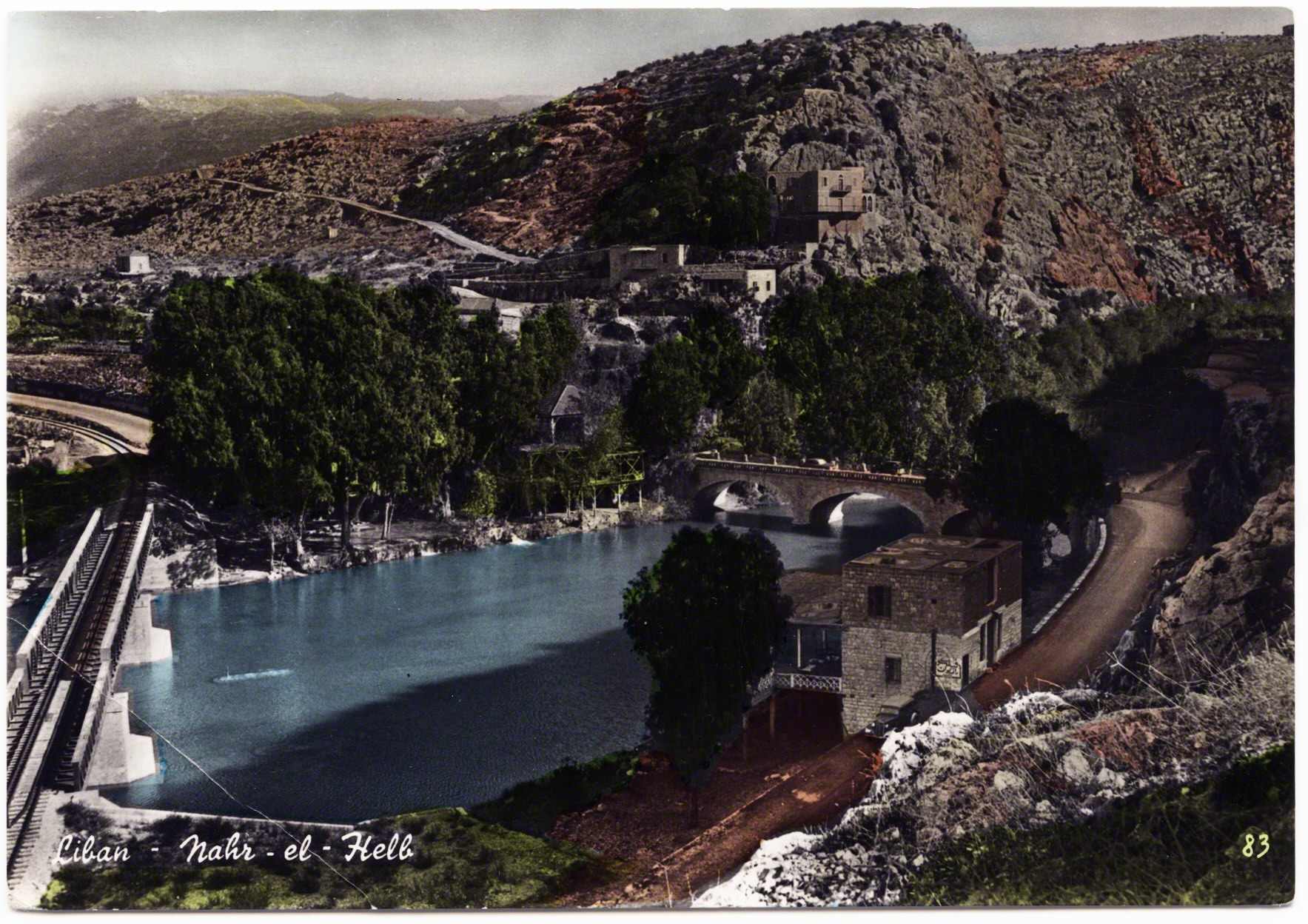

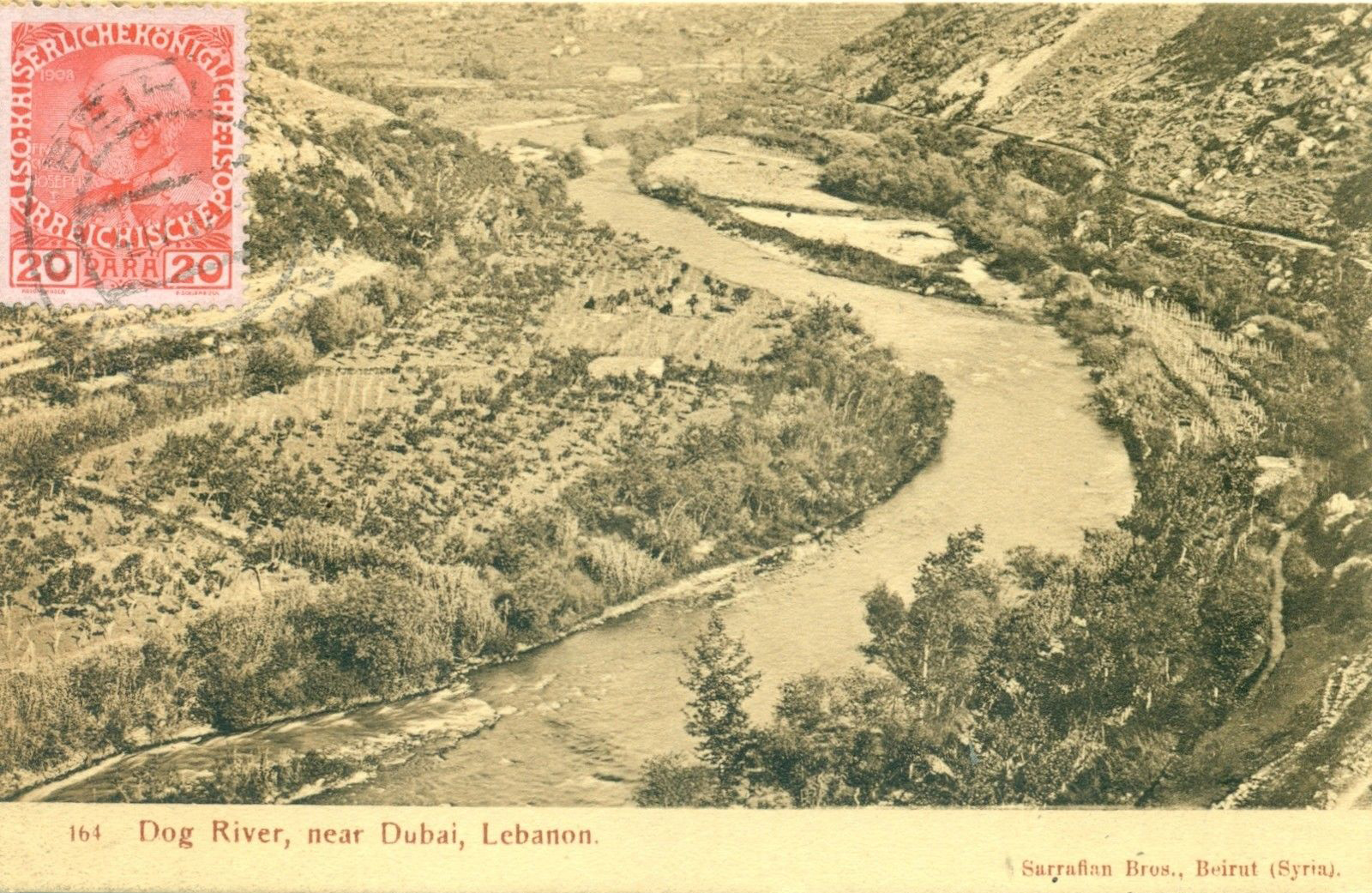

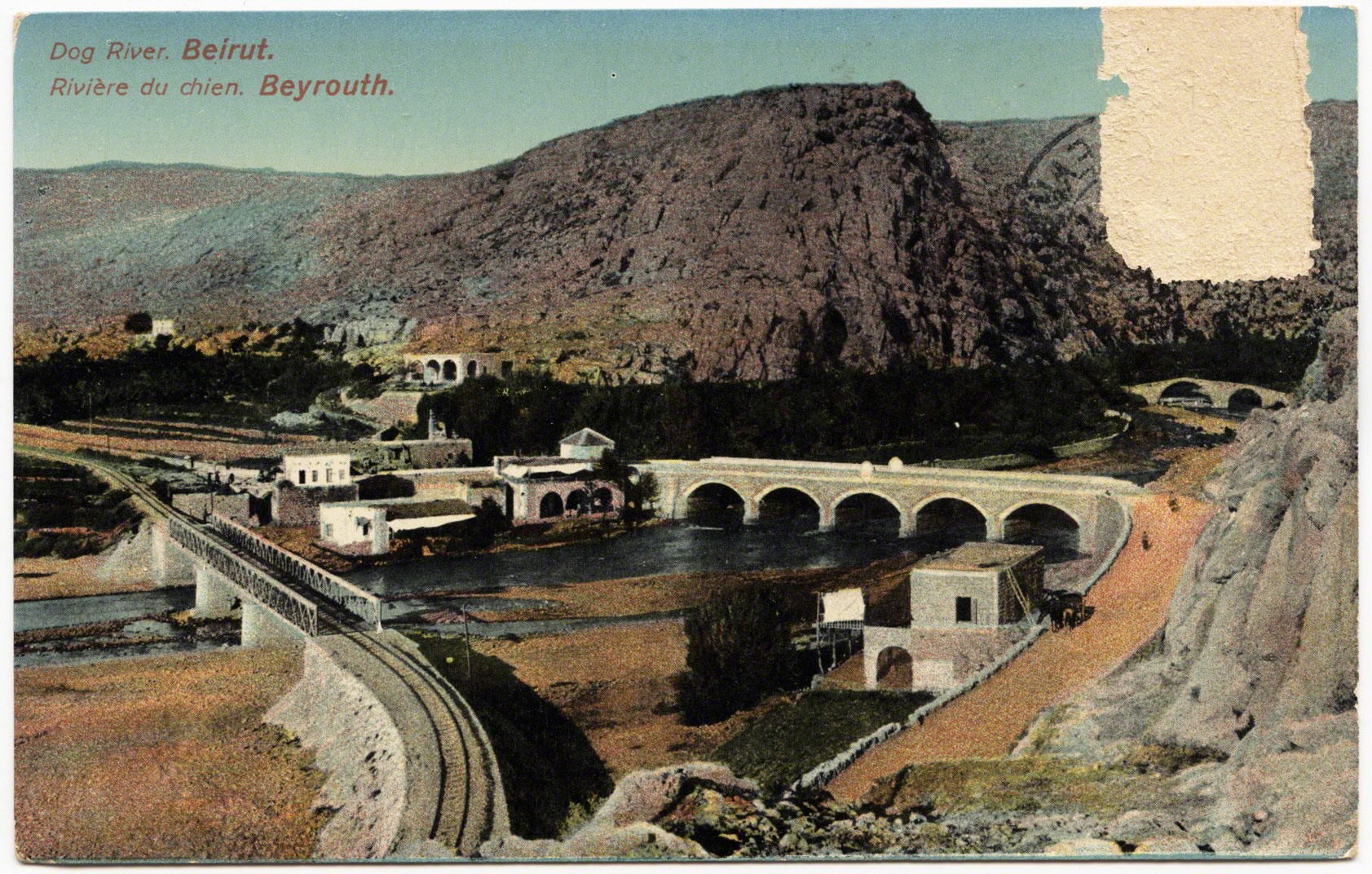

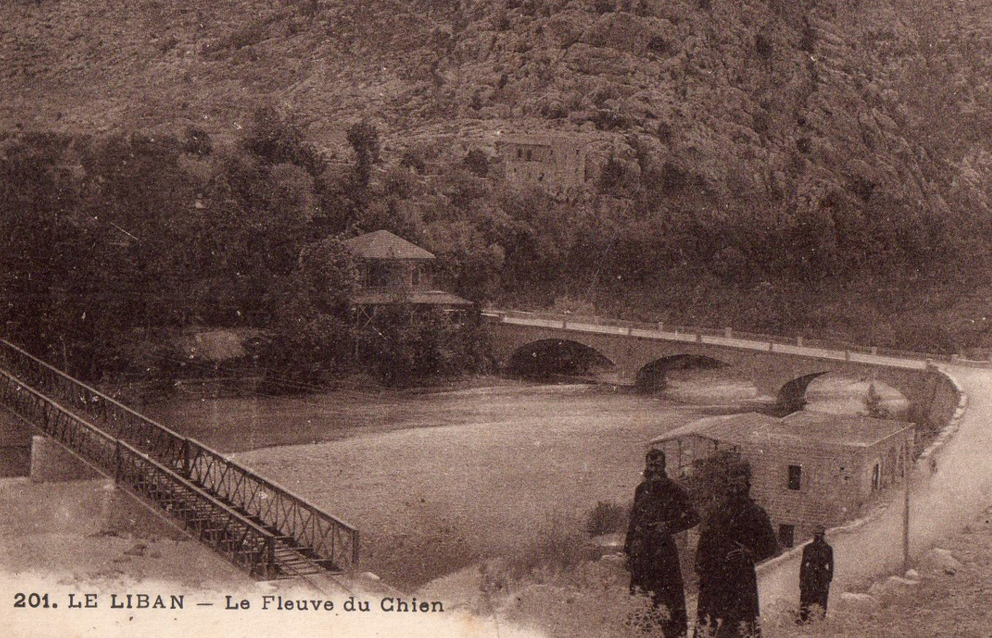

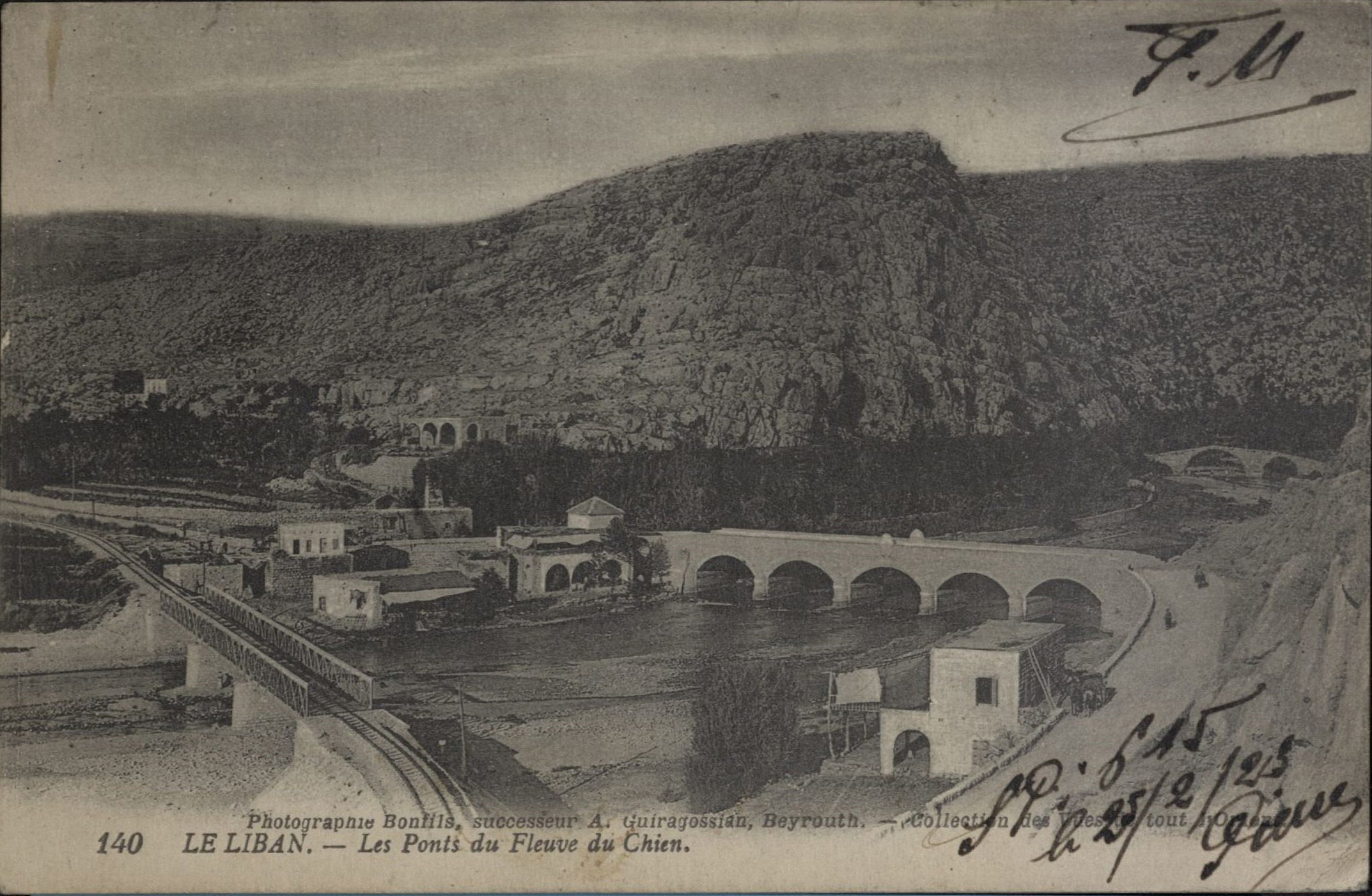

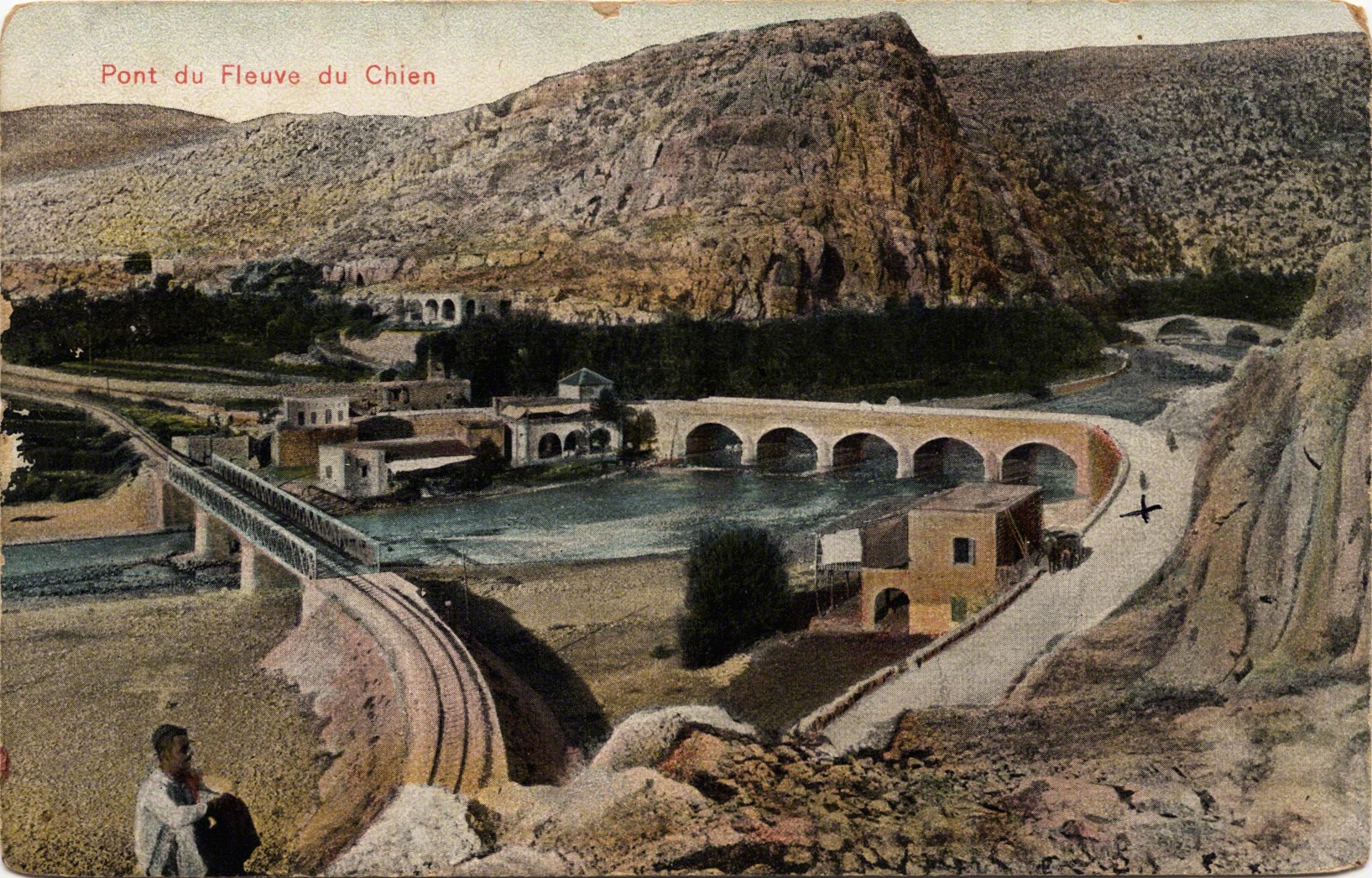

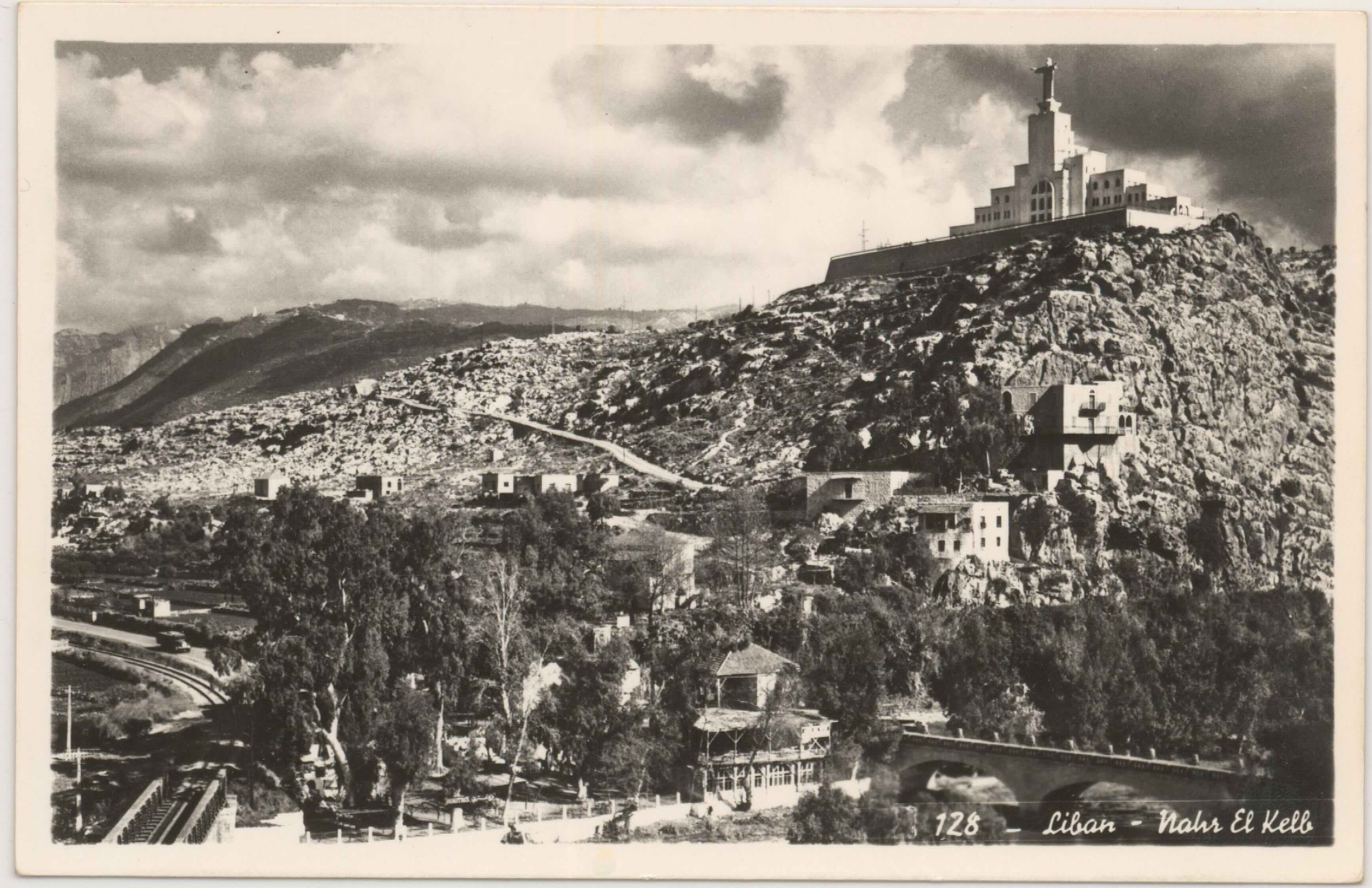

This yellow tinted postcard was mailed in 1914 and is a view looking into Dog River. The next looks out to sea and had a stamp before it was likely removed by a collector. These postcards depict quant views of a uniquely named river meeting the sea, yet the image, and the frequency of it’s appearances, signal other profound meanings.

There are many other origin stories around the name and signification of Dog River: there was a “monster of the wolf species” chained on the banks (Playfair & Murray 1890: 78); on the cliff there was a dog statue that “barked lustily” if it saw a “hostile ships” and his cries would be heard in Cyprus (Learly 1913: 34); other said there was no dog but just the wind’s howl. Or was this site nothing more than a milestone on a well-worn path where the path narrowed?

Rihani writing in Arabic cited a myth in which travelers had to answer the dog’s “puzzle;” safe passage across his river found only in a correct answer (1930: 13). If the traveler failed to solve the puzzle, “the dog swallows him without breaking a single bone!” (ibid). Rouchi also writing in Arabic noted a white rock statue of a dog overlooking the sea and the dog’s face was carved on the rock face itself, and was used to detect the invasion of armies and foreigners (1948:75).

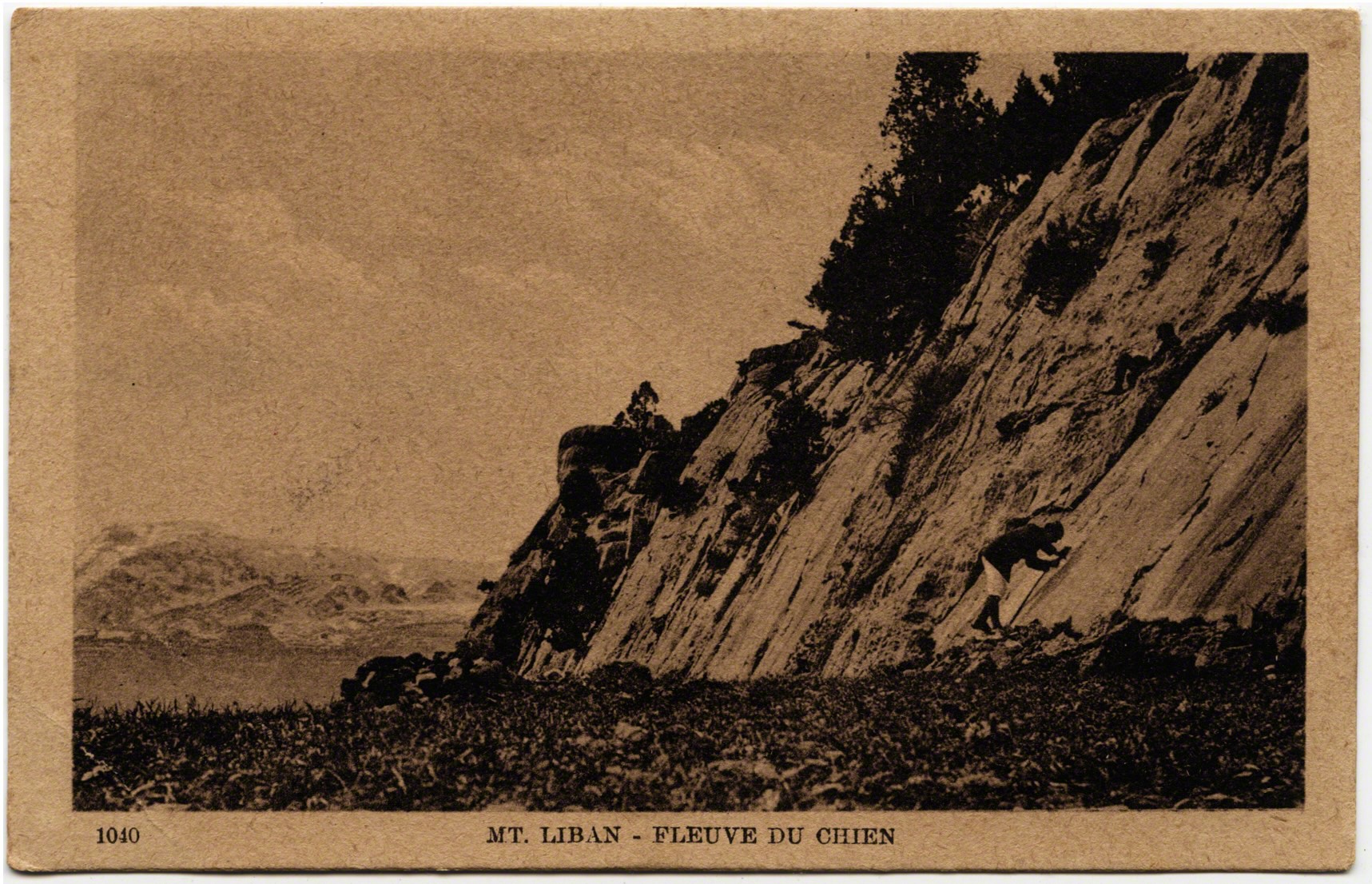

What unites these many stories is the continual passage of invaders, strangers, and foreigners on what amounts to a small path alongside the water and an 80-foot limestone rock-face. As the plaque at the site from the Ministry of Culture notes: a “traveler in 1232” said that “a few men could prevent the entire world from passing through this place.” The historian Hitti echoed this by saying how the “mountain cliffs plunge straight into the sea, providing a strategic situation for ambushing invading armies” (Hitti 1959: 15). Thus it seems auspicious that in hundreds of kilometers of coastline that the natural morphology squeezed passing between river, sea, and stone.

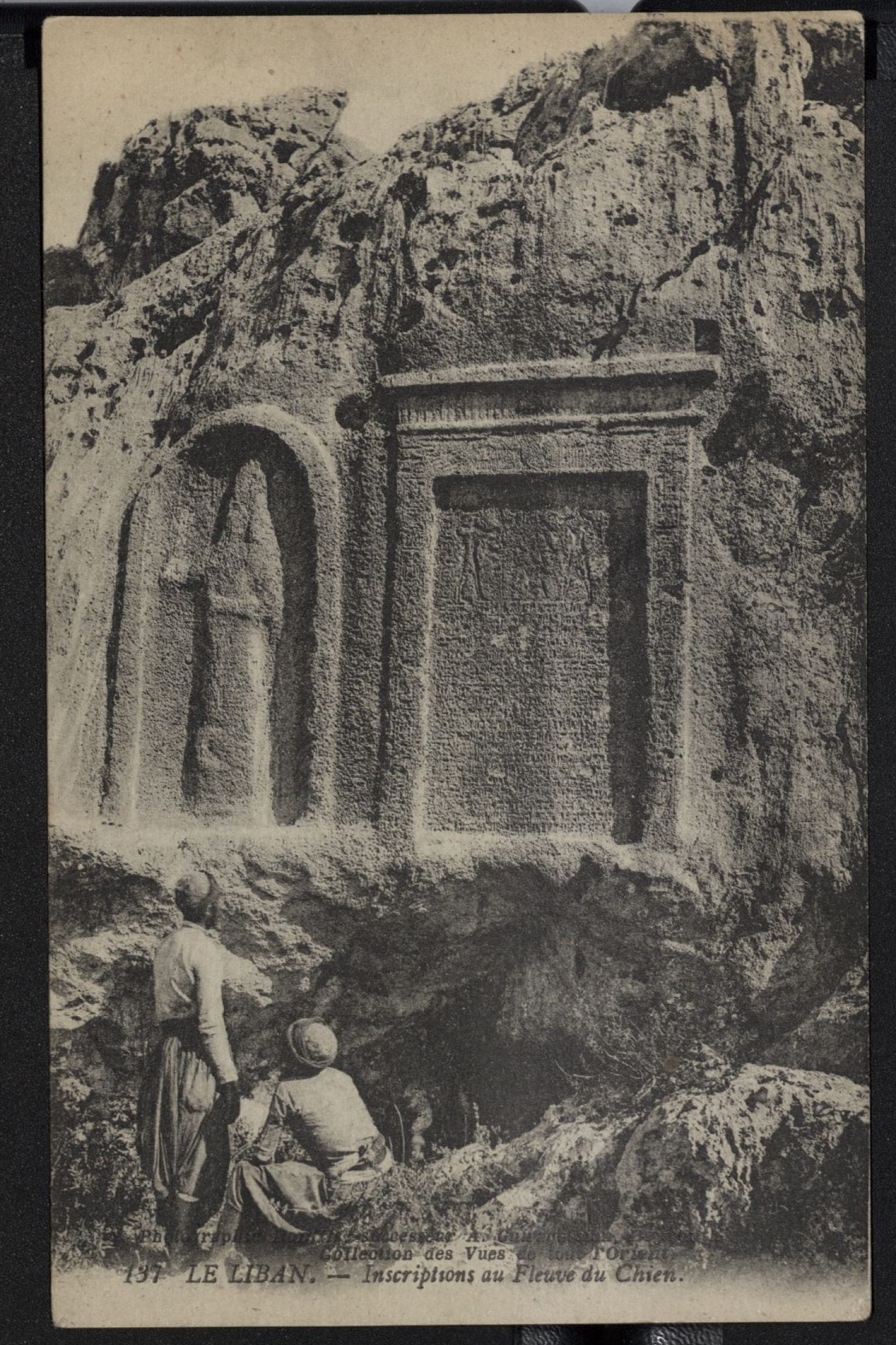

This rock face became an “open air museum” of some 22 stelae (stone carved tablets/faces) from various rulers, kings, and conquerors who crossed this river (Hitti 1965: 134). Men commemorated their passage, and that of their armies, with prayers, proclamations, and iconography that would remain as visual reminders of their presence. Some of those that transited were Pharaoh Ramses II who was famed to have sought out the timber from the cedars, the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar in around 500 BC, Assyrian King Assarhaddon, Romans, Greeks, and many Europeans. The National Geographic Society noted the “proud inscriptions of conquerors who have passed this way since history was holding a rattle” (1923: 123).

In more modern times this included British troops in 1918 and the French Général Gouraud in 1920 on their way to Damascus in the last days of the Ottoman Empire. In 1946 the Lebanese created a memorial at the site on the eve of independence to mark the occasion when all foreign troops were withdrawn from the country (see Volk 2010). The most recent addition was in 2000 to commemorate the liberation of south Lebanon from Israeli Occupation. Thus, the site is a space of national commemoration, a log of mobility, and a contested point of symbolic control.

Many postcards commemorated Dog River from many views. This memorization coaligned with Europeans’ versions of history, as postcards stimulated and connected to a Victorian propensity for “acquiring, classifying, and arraigning specimens” (Guynn 2007: 1162). As well as the numerous travelogues of visitors to the “Holy Land” steeped in orientalism.

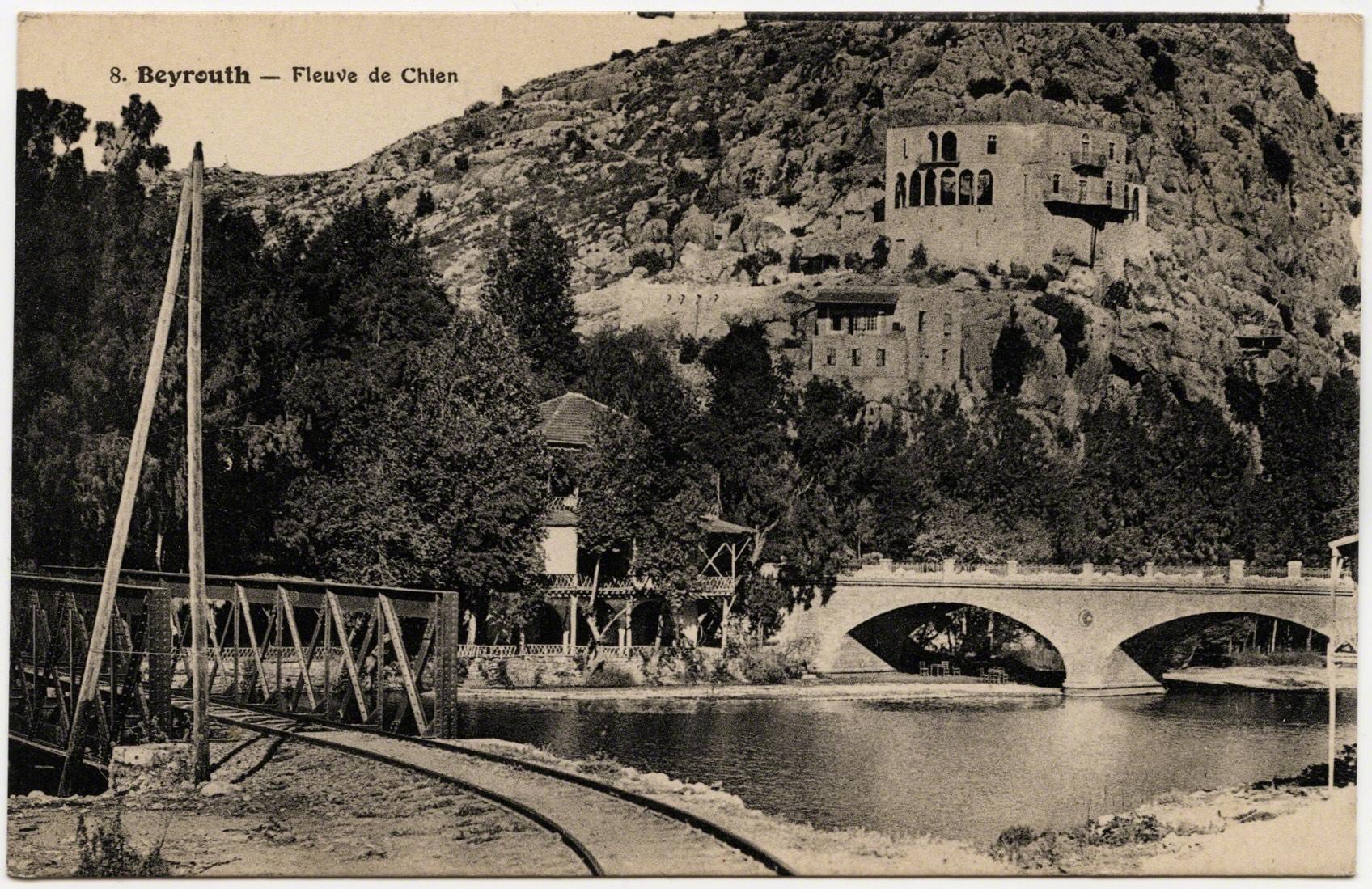

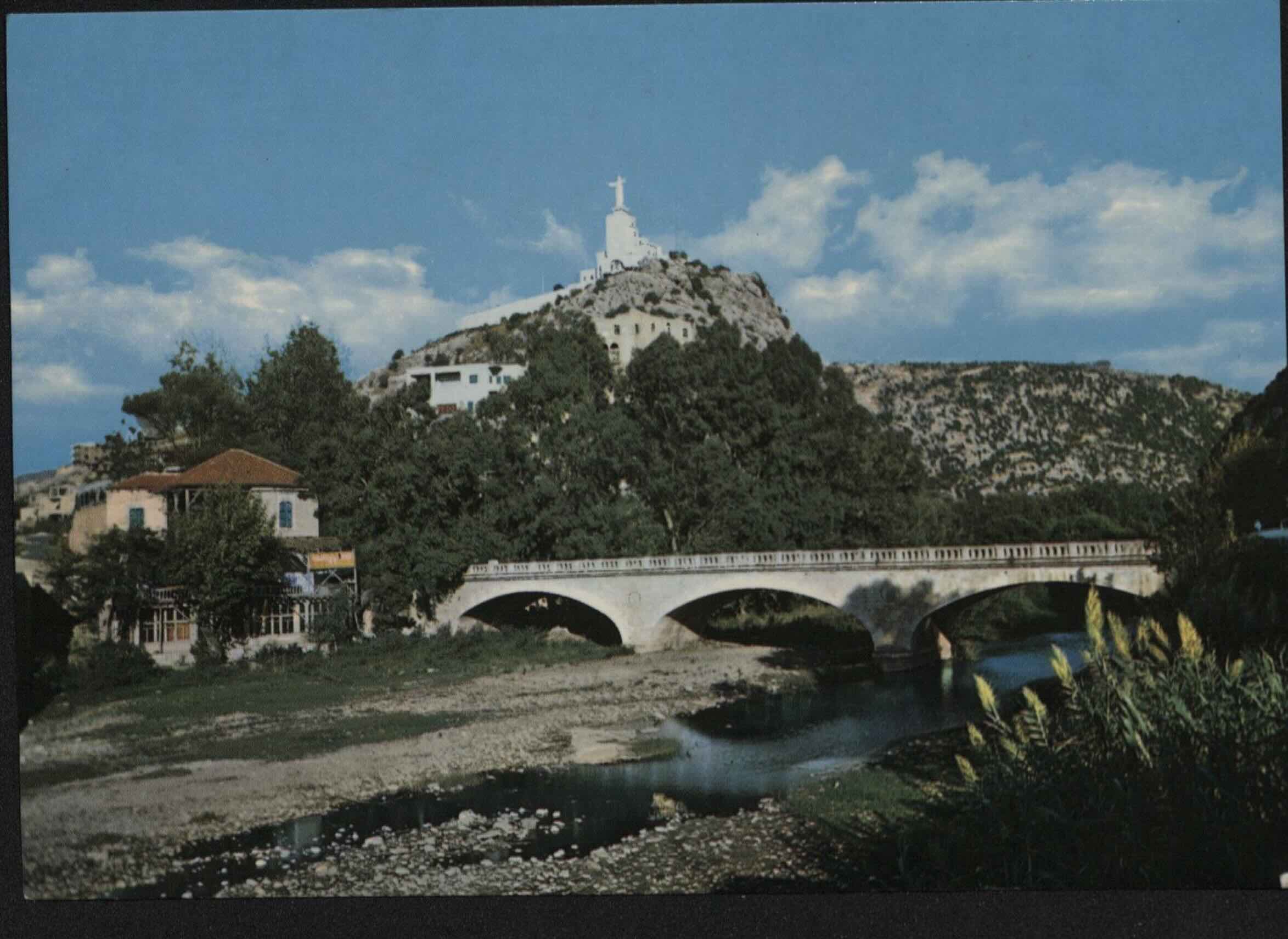

Up the bend of the river is an old stone bridge built by the Mamluks that overlooks newer infrastructures that span the river. As the years passed changing views of postcards paid testament to the French Colonial power in conquering the nation, nature, and as indication of their engineering prowess through the establishment of a series of roads, bridges, and railroads. These French designs and achievements honored on the postcards seem to become as much a focal point of the postcards as the history of “Dog River.”

These infrastructures bearing witness of new control of mobility in this symbolic location. Interestingly, the bridges here are metaphoric and real in how they spanned the river at this auspicious site. The river remained the same, but with a different riddler controlling passage. Were the Mandate officials were now like the “dog,” determining who, and what, could pass ? Were these infrastructures indexing newer ways of marking one’s presence similar to a stone etchings? Like many colonial representations in the same time period worldwide, postcards became a way to signal the imperial authority, their capabilities, and certain views of modernity. As such, postcards became a “constant reminder of the imperial condition that establish the basis for modern cosmopolitanism” (Mathur 2007: 100, & see Mathur 1999).

From my own appraisal (and collection of postcards of the Levant), Dog River slowly started to recede in the visual register as the views turned northward. New sites up the coast signaled new attractions and priorities. There are fewer and fewer (re)productions of the river and stelae by the 1950/1960’s.

A UNESCO publication of “Memories of the World,” imagines these stelae as a testament to Lebanon's "relations with the rest of the Middle East and the West" (2012: 176). Volk notes that Dog River references the Lebanese’s "multicultural past, and their heritage as a cross-roads for and between ancient civilizations” yet it also begets noting that being at the crossroads “has not necessarily had a unifying effect” (Volk 2010: 19). Crossroads are powerful but volatile.

Given this, how might we think of these stelae similar to postcards - as “graffiti” chiseled in stone - in an inverted likeness of a postcard? Rather than being mailed from afar to mark the “having-been-in-this-place,” the stone marks one’s passage and presence in the location. Both the stone wall and the postcards quintessentially index mobility: the movement, a passage, and a visual memory of it. The plaques and etchings at Dog River monumentalize a “being-in-place” at the river, while postcards do similar work but through a circulation and view that lends one to think the sender was there.

In this way I’m positing postcards as a juncture between an impression and an expectation. This impression has a fixed boundary and frame through its composition, just as it is imprinted in the likeness of an image, a momentary imitation. More importantly, this impression presented boundaries of our senses for thinking about place. This could be a common stereotype of the people, city, or ways of life that transpired in the “real” location that was depicted. Postcards could reinforce these conceptions of place, or challenge them. Yet at the same time, through the postcard’s propulsion, there was a public proclamation of this location. Through a sense of desire, realized on a vision from the postcard, it might say “I went.” “You should too.” “Look what I saw.” “Wish you were here.” It also might have an x marking where I stood. An index of person in place on a mass produced surface.

However, like any image, there is a deception in postcards. A duplicity, because they are duplicated. It signals one’s location and hints to a view, a landscape, or what one might actually have seen - but didn’t. My eyes met with a likeness depicted from the card, or an idealized version of that vista, outfit, or sculpture - but wasn’t. The sunset from a different day. So there exists a certain objectification and representation that becomes essentialized through the genre of postcards and in this act-of-being-there (see Sontag 1977).

In this regard, Kracauer is instructive in framing a relationship of imagery, place, and mass-media through his meditation on surfaces. In a series of essays grouped into the Mass Ornament (1927) and On Photography (1927) Kracauer questions the interconnections of pop-culture, distraction, and changing relationships at this same moment in European industrializing societies. He said that the “ornament” was a “mere building block” of mass culture and was the removal of the individual in cultural production (1927). This faceless repositioning through modernity presented “a new type of collectivity organized not according to the natural bonds of community but as a social mass of functionally linked individuals” (Levin 1995: 18). As such, ornaments were made of “insignificant surface utterances” and they “resembles aerial photographs of landscapes and cities in that it does not emerge out of the interior of the given conditions, but rather appears above them” (Kracauer: 1995: 76-77).

Koch wonders how much the “surface,” in Kracauer’s work, is merely a way to conceptually connect back to his concern of the masses/mass ornaments (2000: 28). Given this, how might we understand the role of the surface if all of society dreams in the “form of its ornaments…the dream thus illuminates the dreamer” (Koch 28). The framing of the postcard becomes the vessel into which we pour our own desires and projections - just as they are projected out into the world.

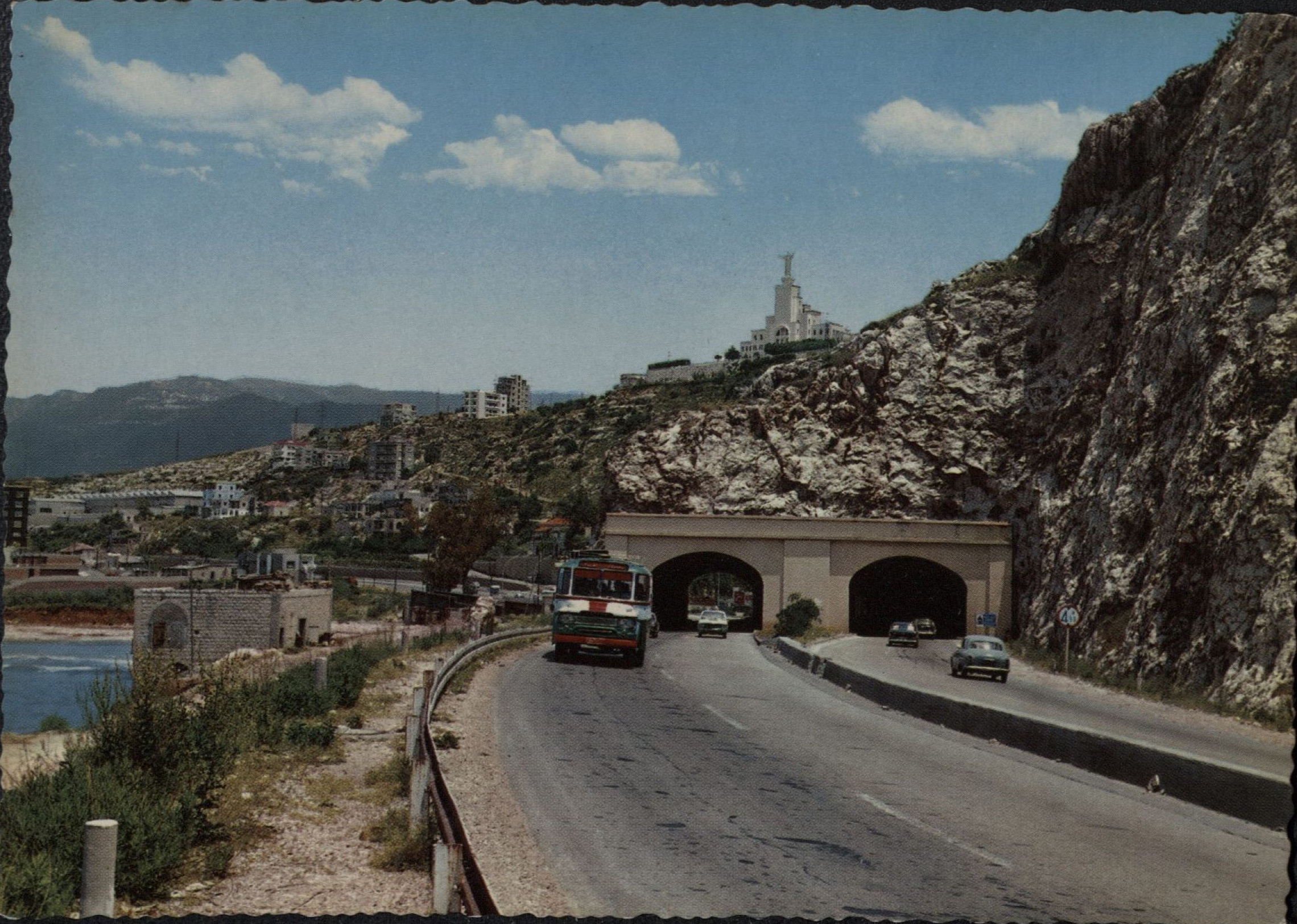

This final card is of a highway tunnel. I runs directly under the oldest inscriptions from thousands of years ago. To accomdate greater mobility at this bottleneck of Dog River, the Lebanese State bore through stone to create a modern highway. This passage now takes us to the next actor above the Bay of Jounieh.

=========

III Landscape of a Virgin

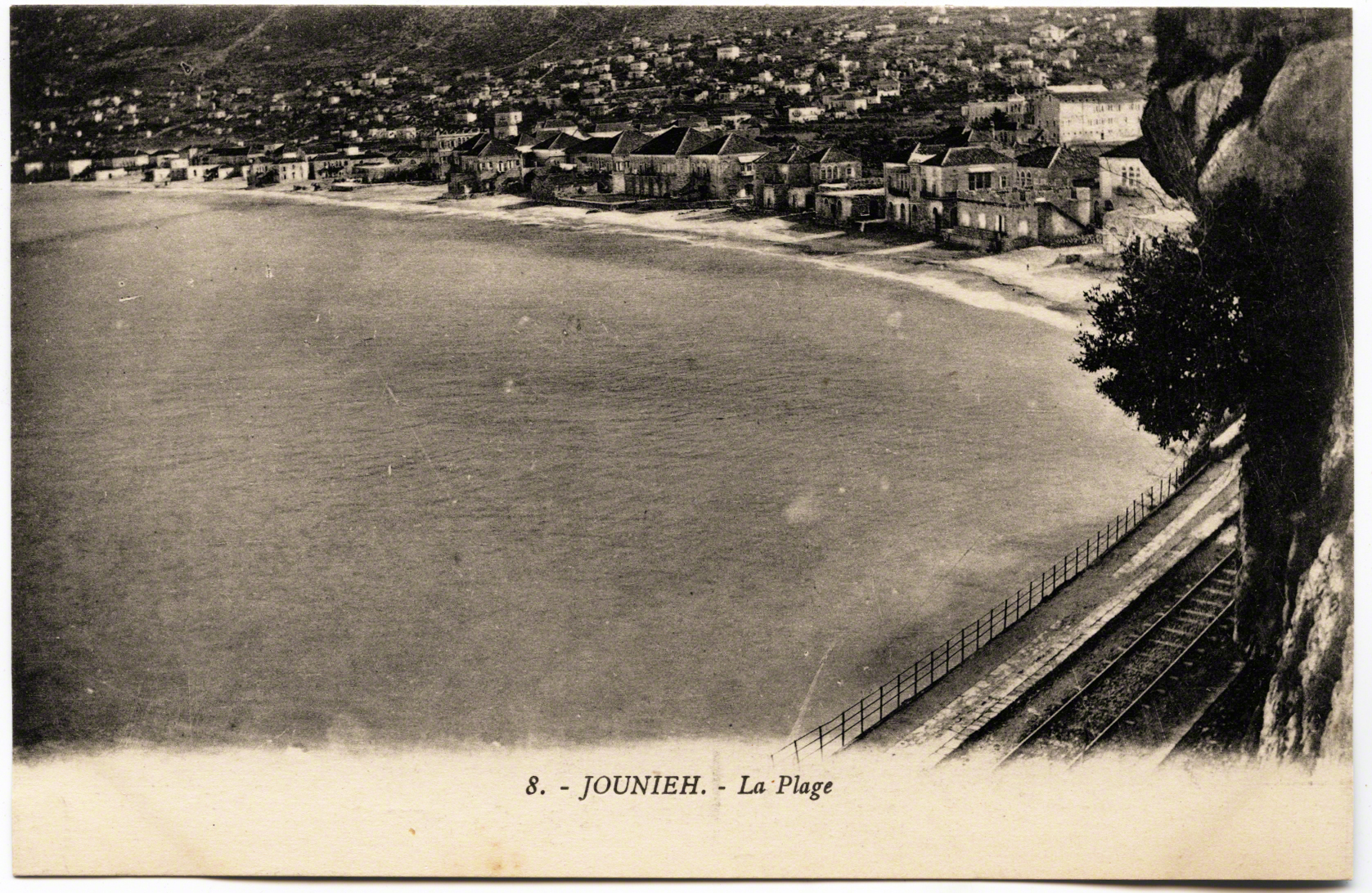

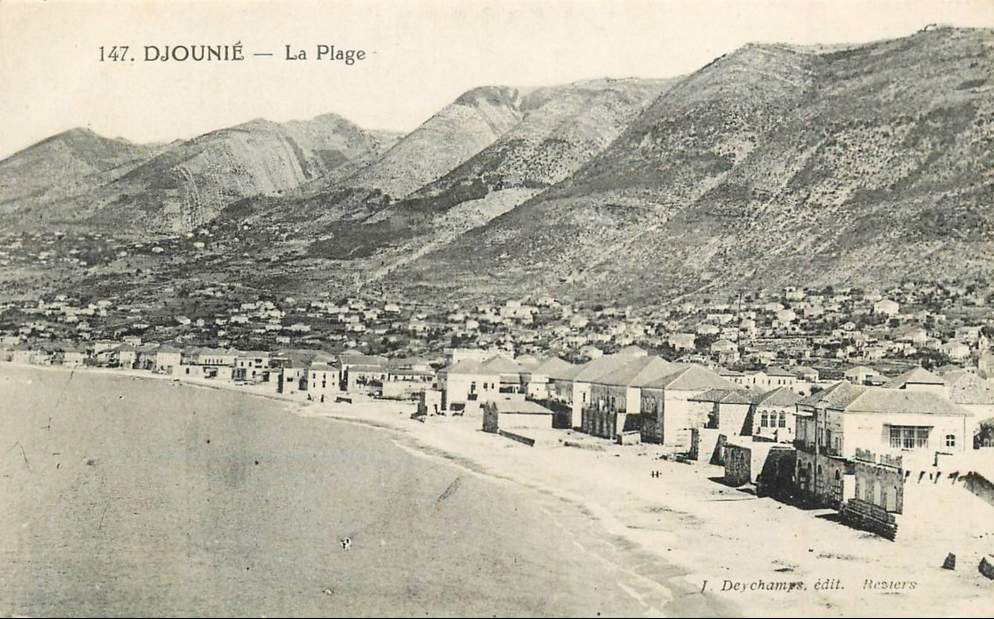

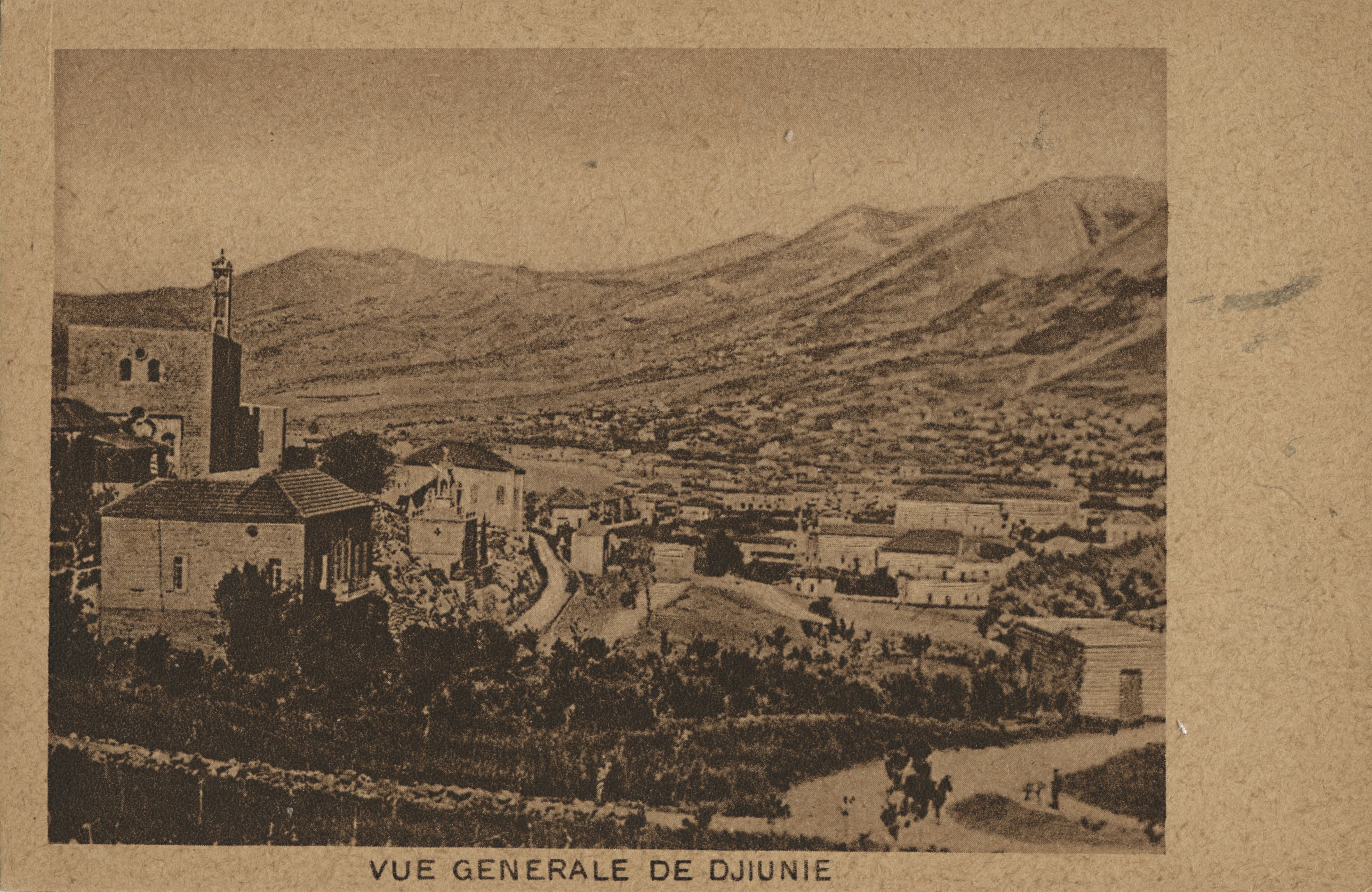

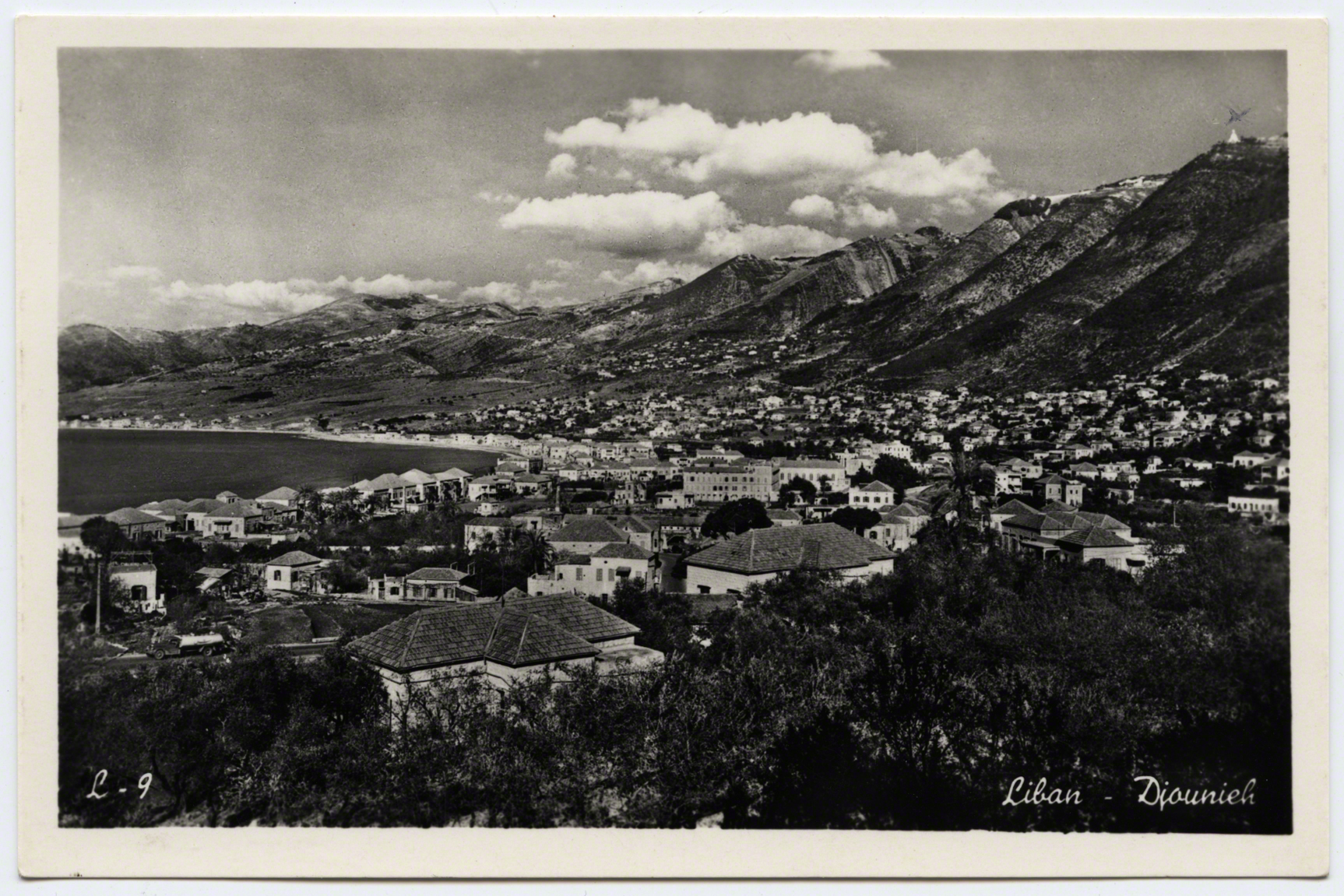

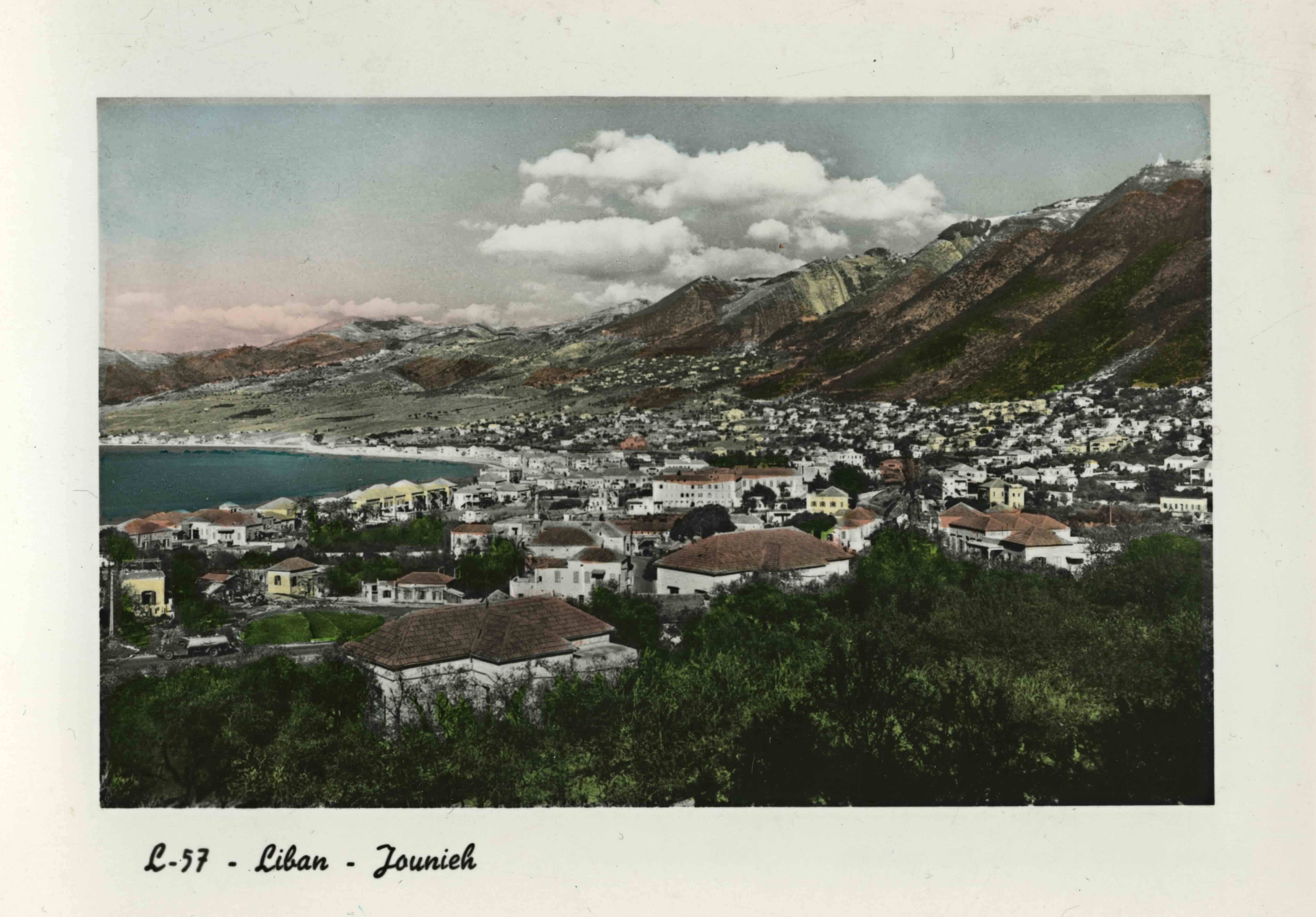

Heading Three km north of Dog River, one would turn east into Jounieh. The landscape was sparsely developed and it was a small fishing village at the turn of the century. Within years, in the distance, above the bay, an effigy of the Virgin Mary would come to overlook this area.

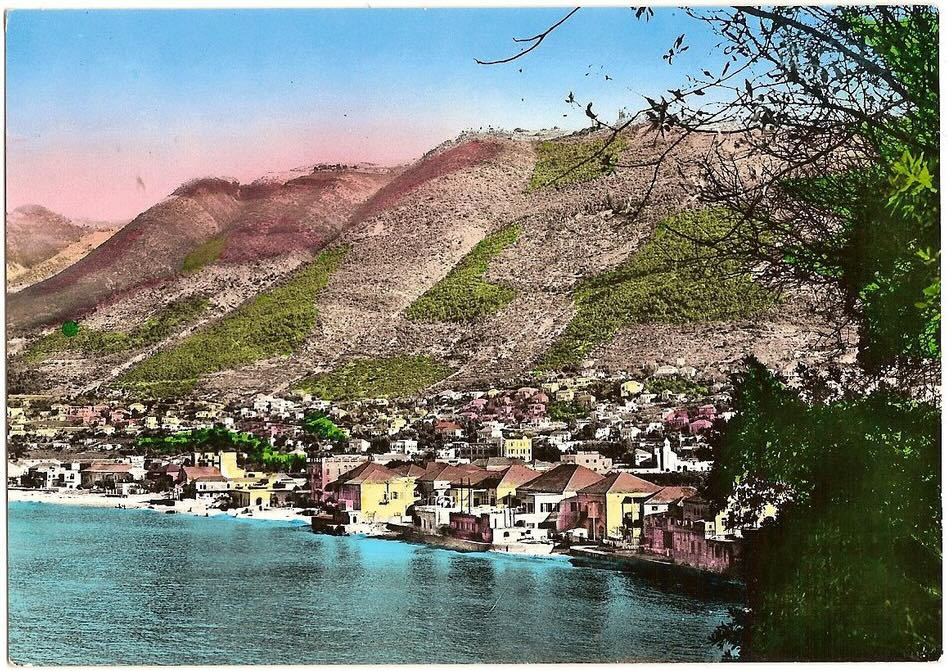

This flipbook presents the views and role of the landscape to consider the relationship between land, nation and the bodies that populate it. “Above all,” Tilley writes, the landscape “represents a means of conceptual ordering that stresses relations.” (1994: 34). The postcards here illustrate a serial scripting of the landscape and sedimentary layers, built upon one another. They crystallized certain views not just visually, but conceptually. In this way, landscape becomes a “cultural process” and tourism is a lens to think of these changing views and paths (Ingold 1994: 738 & 2007).

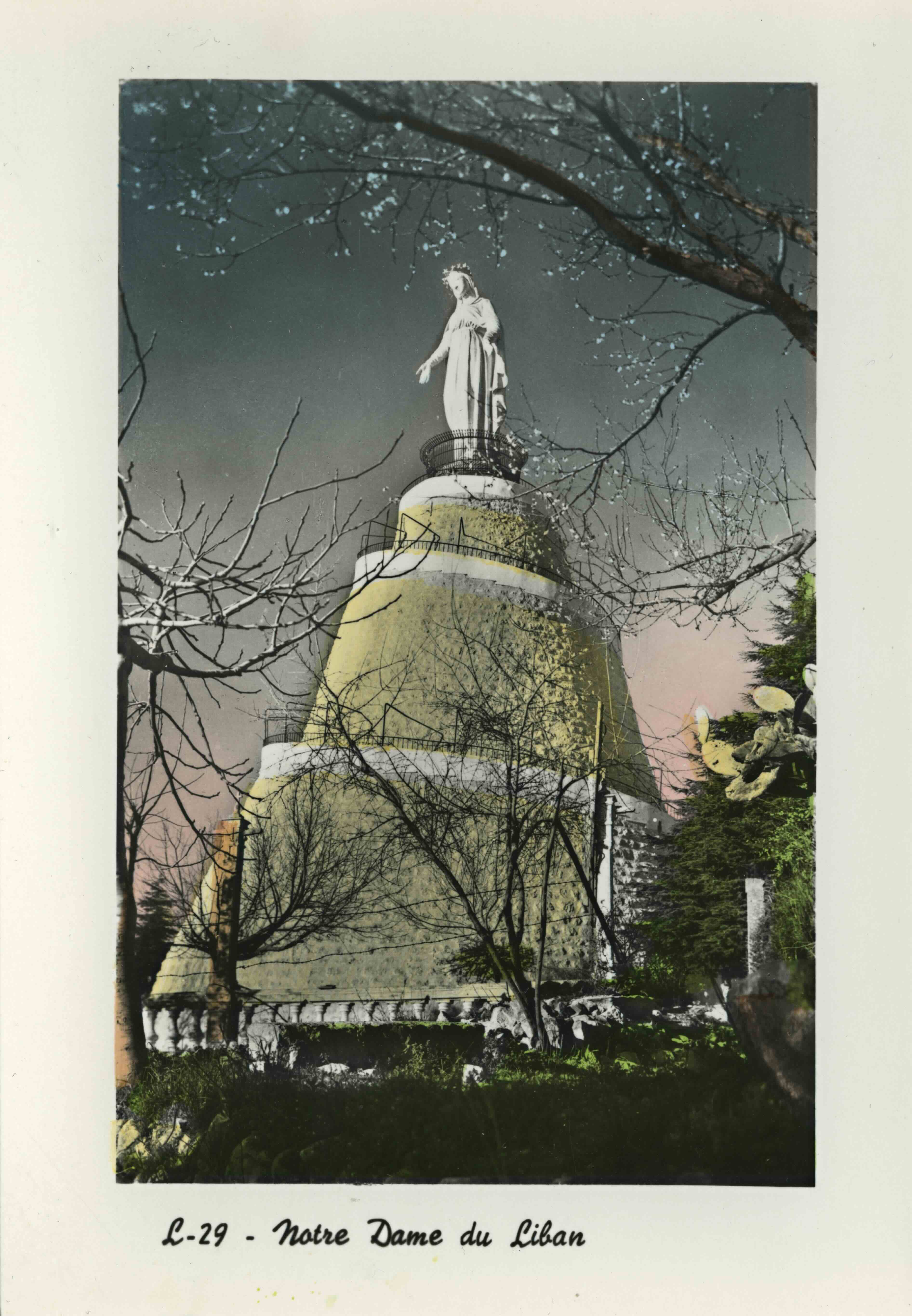

In 1904 the Maronite Patriarch Hoayek conceived of the idea to erect a statue of the Virgin Mary to mark the 50th anniversary of the “doctrine of the Immaculate Conception” (Durward 1908: 753). Mary was built in France and mounted in Lebanon in 1908. The statue was placed above Jounieh in a village called Harissa, which was the location of a long standing convent.

John Burckhardt, a pilgrim to the "Holy Land" from England, noted of the village in 1822: "Harissa is a well built, large convent, capable of receiving upwards of twenty monks" (184). Another priest, in 1830 noted the view from this spot in the terraces of the convent: “is extremely beautiful, commanding the bay of Kesrouan and the country as far as Djebail (Jbeil) on one tide, and down to Beirout (Beirut) on the other. Near it is a miserable village of the same name” (Conder: 159).

The Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Lebanon, would eventually take a shorter name. Her location became her name - Harissa - just as her presence indexed those who wanted to mark this area as a solidly Christian territory. Watching over the slopping lands she became an important site of pilgrimage and visuality. We not only see her, but imagery as if from the perspective of her eyes, the claim of control over which she governs. Jackson’s work on “vernacular landscapes,” in which a view is indexing a political, but also a social world, is relevant to Harissa (1984). Her perch on the mountain, and the huge number of postcards around her index, over and over again, mark the presence of Christianity and the development and urbanization of the Bay of Jounieh.

The placement of this physical statue is significant but so is the linkage of her body to the landscape. The landscape on which she emerges, to the larger body of the nation. Such imagery might make one think that the nation is filled with certain types (Christians) that live below her feet. The images of her, and the bay of Jounieh, are linked henceforth in postcards.

Historically there was always an interplay between photography, landscape, and the way in which the nation was built (see Taylor 1994). These postcards are then an outward face and representation of certain vistas/views. In the context of Paris, Schor juxtaposed postcards in order to illustrate aspects of the “discourse of the metropolis” (1992: 195). She showed ways in which the city was changing, but also how those changes fed back into narratives of the place itself, folding meaning and vision together in a reconstitution (ibid). We might also question the landscape and environment here as foreground and background, what was being accentuated and focused on while what was auxiliary filling the background. "Foreground actuality and background potentiality exist in a process of mutual implication” and daily life will never match those “the idealized features of a representation” (Hirsch 1995: 23). Thus the foreground and background became an interplay of possibility and promise.

There is much more to say for the role of Christianity. How much did these postcards contribute to sectarian identities of belonging and religious ideologies? What would other faiths think of Harissa being reproduced as a face of their shared country? What about Christian entrepreneurs profiting off building a tourism industry, or the the long and complicated ideological/religious orientation of Lebanese Christians with France? Lest we forget that Napoleon’s journey in 1860, so boldly marked at Dog River, was to protect the Christians in sectarian fighting, the French General Gouraud, in 1920, proclaimed Lebanon a "safe haven" for Catholics.

Take for instance these three following cards which play with scale: first, before the days of Photoshop, she looms totally out of proportion over the bay as if to increase her prowess; second, we oddly see a view of her looking south, as if she were looking over Beirut in the distance; third, the view she might sees from her marble eyes. The entire bay of Jounieh is visible from North to South..

In addition to the powerful work that these cards do in staking a claim to the land and nation, many of these postcards became for Diasporic consumption. Earlier cards were often produced for European (colonial/imperial) interests but many waves of Christian emigrated worldwide and they came back to Lebanon as a form of tourists. In terms of the landscape these postcards also do other work, they create new paths. Postcards provide coordinates in the world, or simply put, they are “geographic information” and “representations of place: the scene of the seen” (Arreola 2012: XV, 2). Thus, they speak to the paths that we traverse as mobile, touristic, bodies, as well as show us the “idealized” routes on which we should remain in order to “see” these same views. A path implies not just where we put our feet, or the ground which bears the markings of how narrow, deep and worn the land has become, but paths are also a cultural act. They guide us. What does it mean to go off a path - to stray, get lost, or divert? Paths are like channels that normalize a transit, lines, or directions. If paths guide our movement then postcards serve as mile markers that position us. They signaled where we are, where we want to be, but also where we should be. In this regard, part of what I posit here - and explore visually in a digital project (related to this piece A View from a View) are how we become trapped in such paths, such narrow definitions where our bodies swirl in an eddy that is crafted with intention for a tourism “industry.

By the age of mass-tourism another concern arises, where do these paths lead to? One of many places that would develop in the bay of Jounieh was the téléphérique. It connected visitors from the seashore up to the feet of Harissa. It was founded in 1965 and was owned and operated by Compagnie Libanaise du Telepherique et d' Expansion Touristique. Private entrepreneurs would pour money into the development of new paths, sites, and sights for mobile bodies. During this “Golden Age” of tourism in Lebanon, Jounieh developed a wider and more robust touristic economy, not just as a destination, but also as a midpoint to other sites in the nation (i.e. Cedars).

Ironically, this flipbook of images returns to Dog River. Before the téléphérique was initiated a statue similar to Harissa was built on a hill on the opposite side of most of the stele. Jesus the King (Yessou7 al Malak) was built in Zouk Mosbeh, on the Northern side of Dog River. It was a statue of Jesus, with his arms flung wide open. Just like his mother a few kilometers up the road he faced westward out to sea. Welcoming and watching - or perhaps warning, like the original dog statues. In this image a modern highway took the place where the railroad had once stood. The French and Mamlouk bridges both step back in into the depths of the valley, stagered bridges of time.

This location from where Jesus the King rose was historically a site of an old monastery and church. As the myth goes (from the Lebanese Ministry of Tourism), in 1895 during the Ottoman Empire, Brother Yaacoub Haddad was on his way to take his monastic vows and he passed the aforementioned inscriptions of Dog River (MOT ?). He said “Christ must have a record in this place, more important than the written and engraved remains” (ibid). It seems he thought Christ must have the larger word in the graffiti battle in stone. Thus, decades later Brother Haddad bought a piece of land on the opposite hill and opened his church in 1951.

He commissioned an Italian artist to make the statue of Jesus which was 12 meters high (ibid). It was installed in 1952 and there is an elevator to the top of Jesus’s head (Kuntz 2000: 155). One might suspect that Jesus the King was partly an effort, akin to Napoleon, to superseded the names of other kings’ nearby. While the views of postcards presented here in the Landscape of a Virgin run laterally, inwards, outwards, and to the coast – both Jesus and Mary have a position on the mountains overlooking bridges, roads, rivers and the sea. Seemingly keeping track of mobilities below, while indexing the shadow of a religious community’s control.

=========

VI Path to a Casino

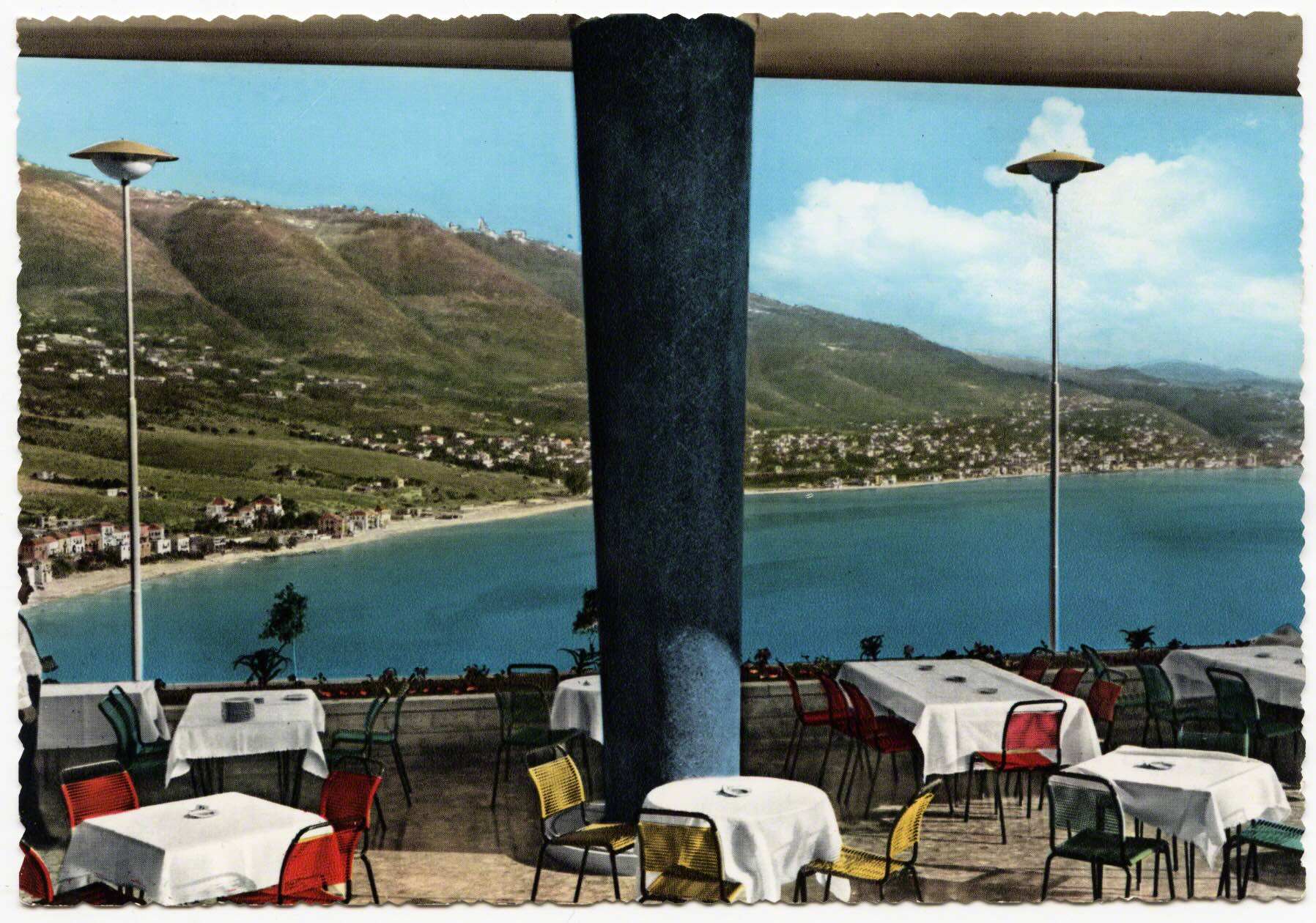

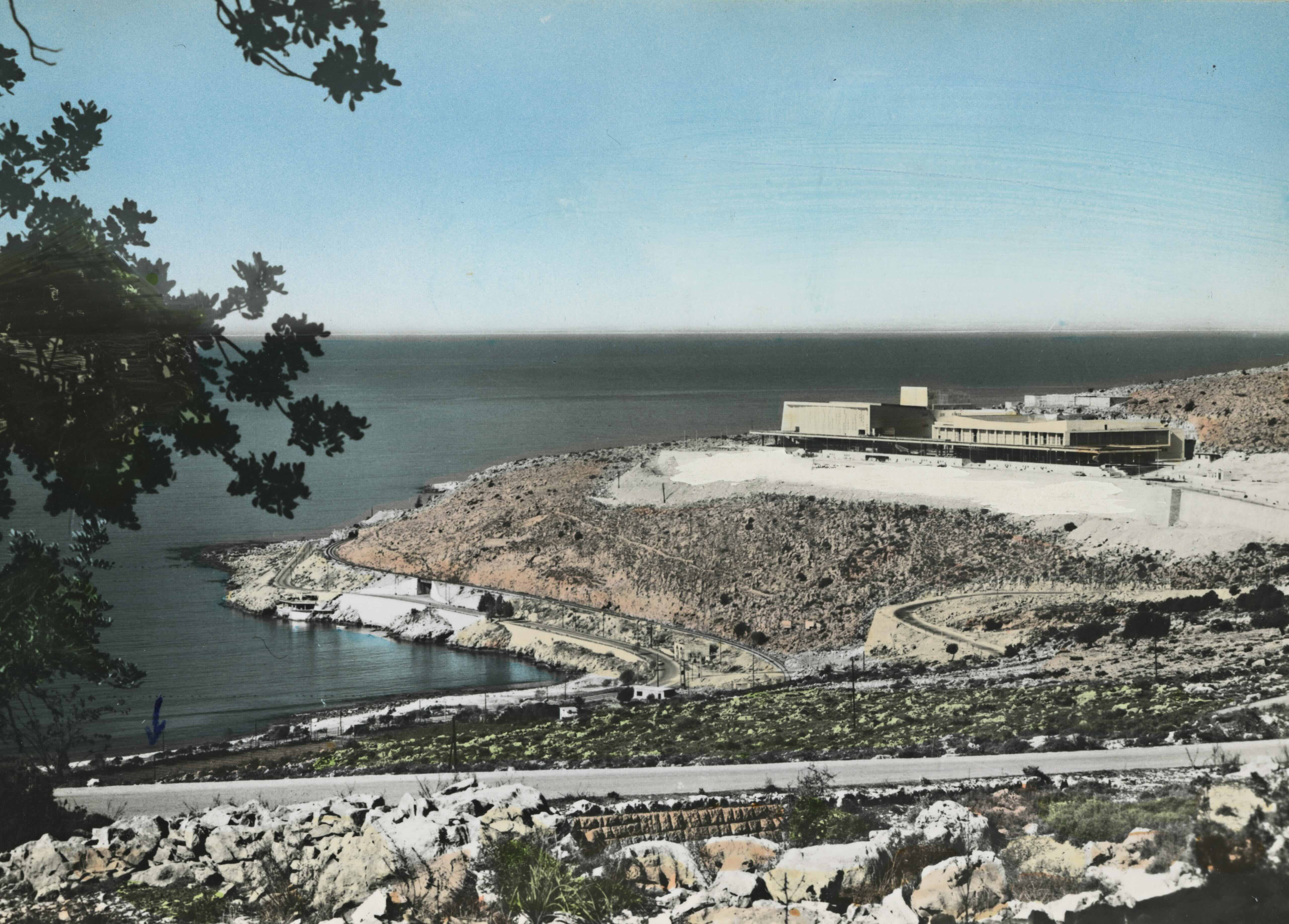

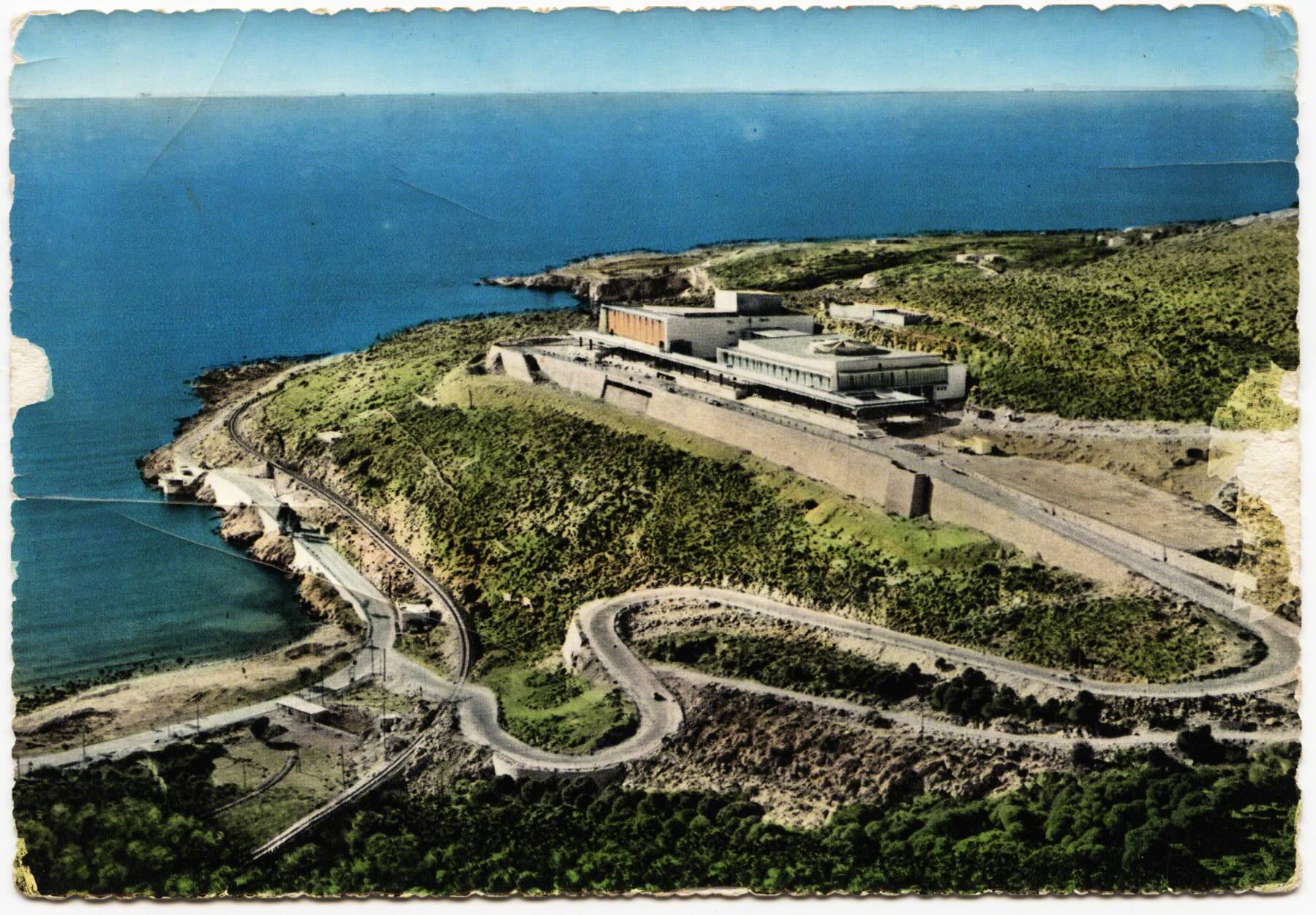

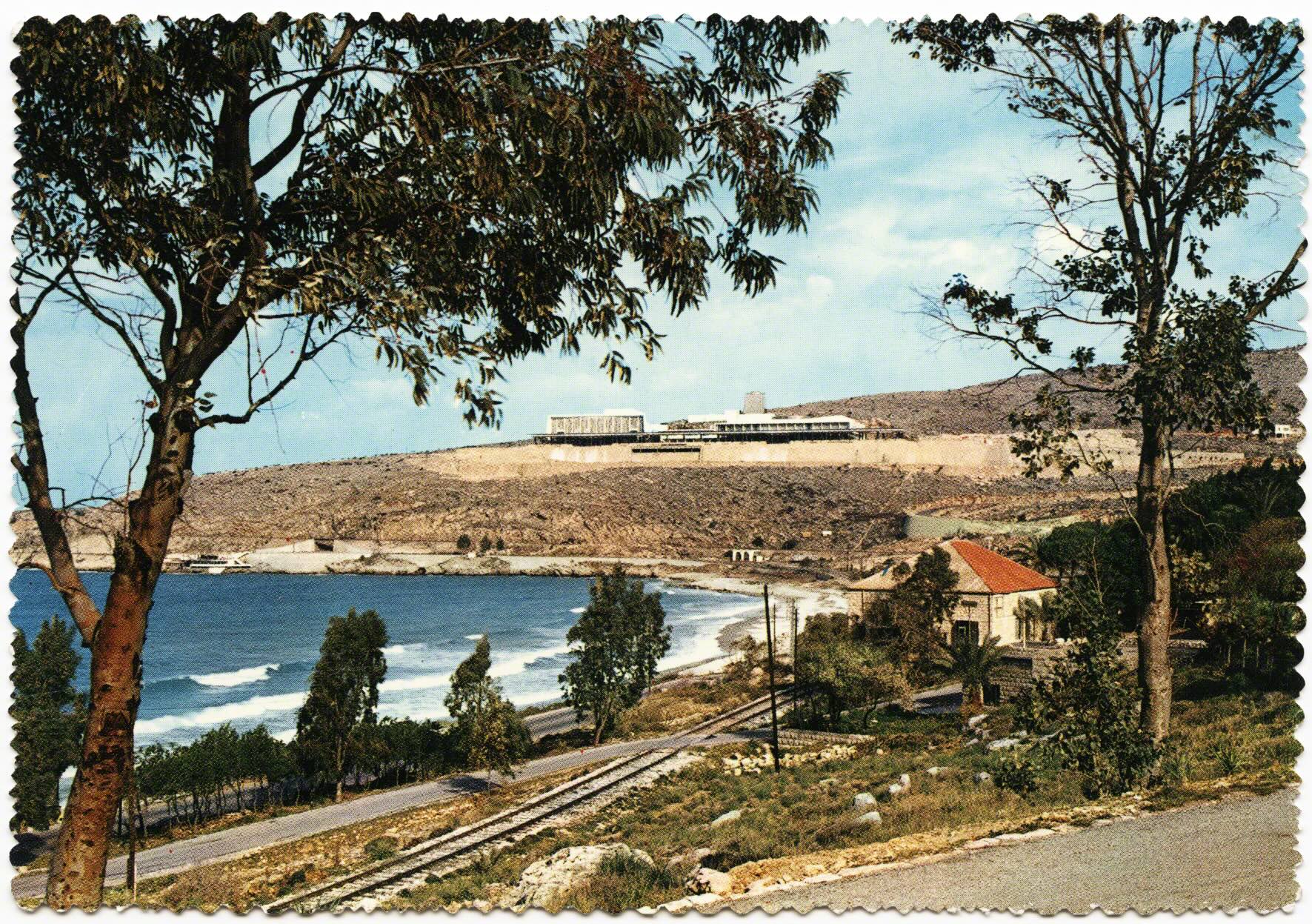

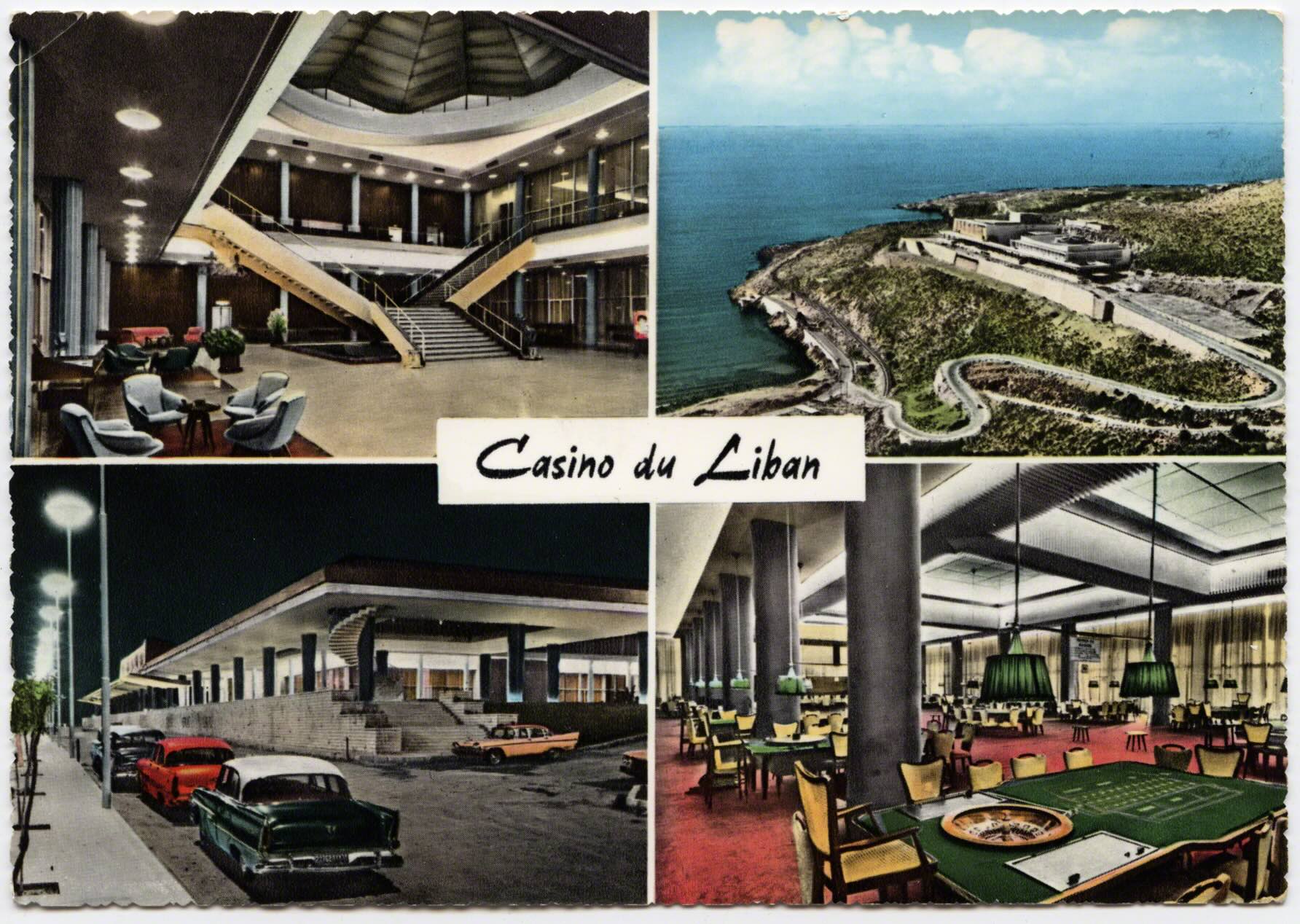

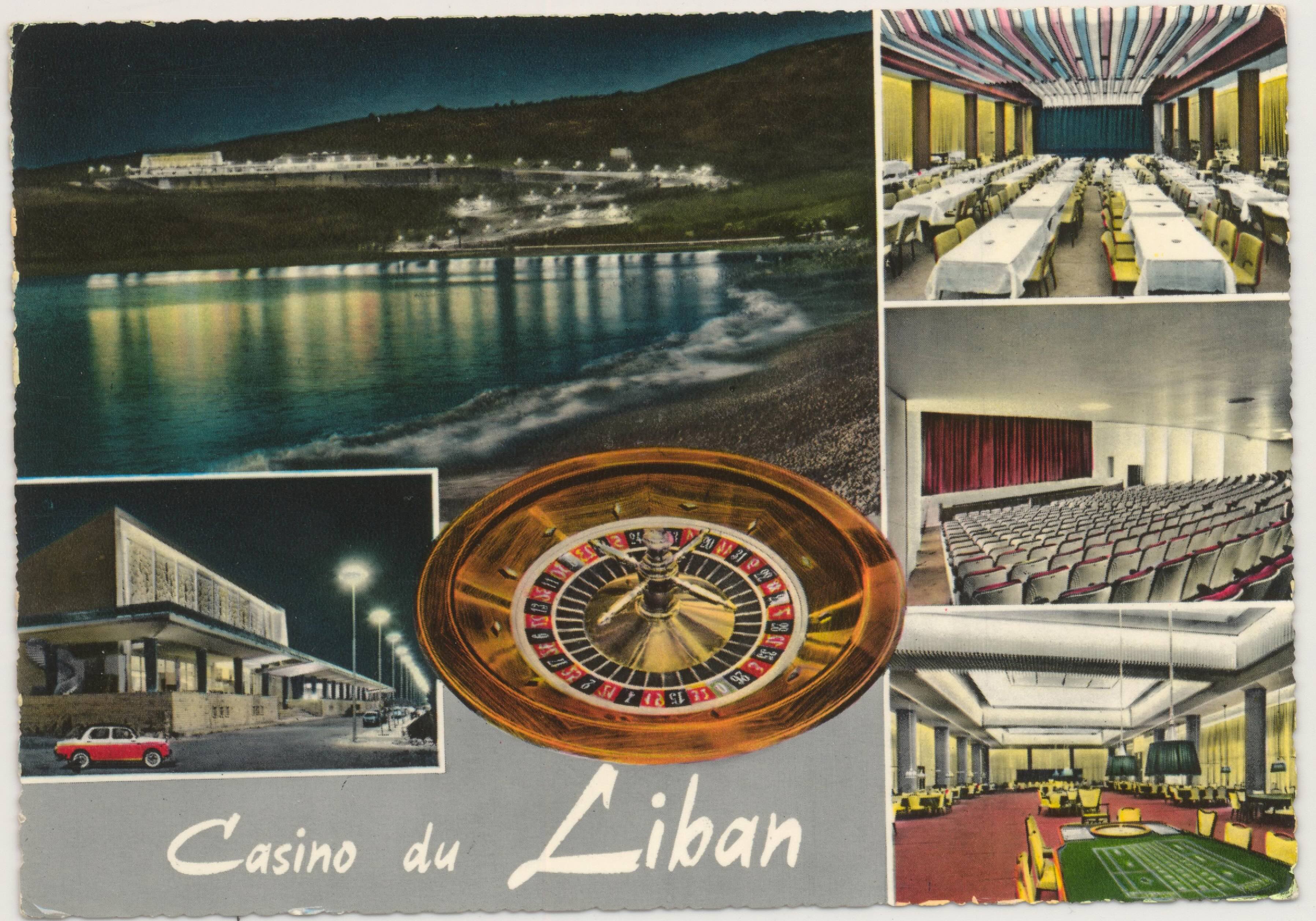

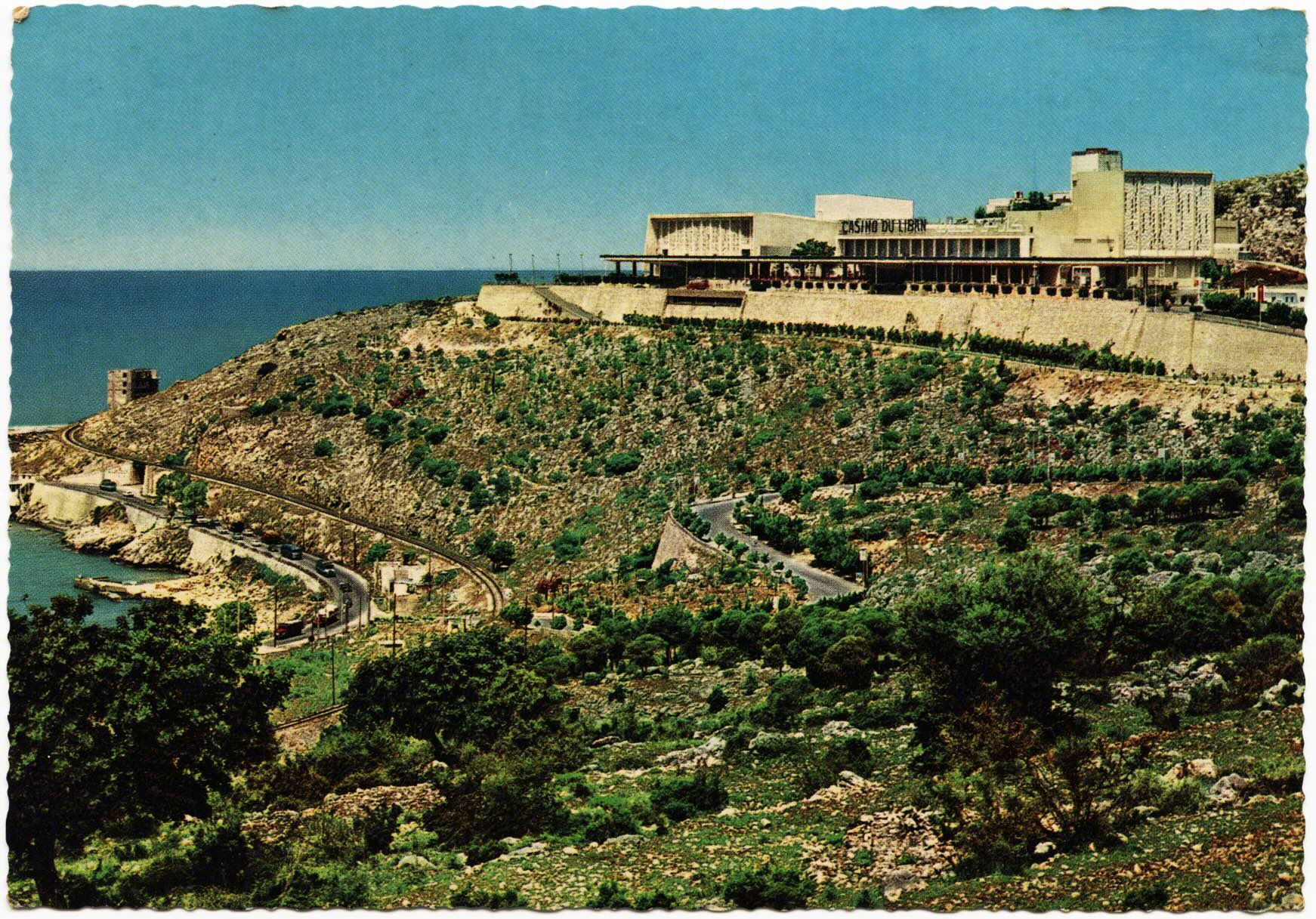

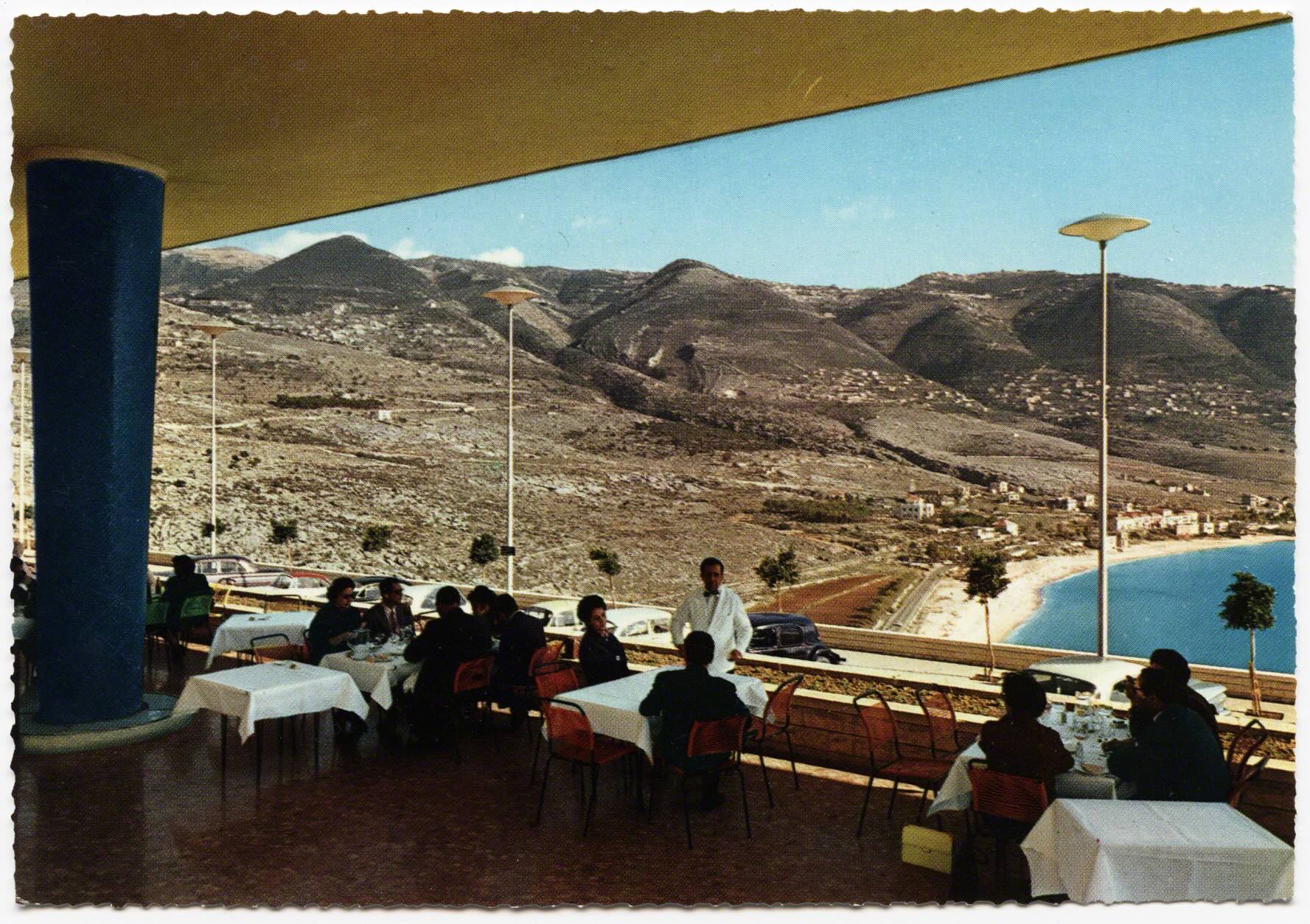

In the fall of 2014 I spoke to a friend in Beirut about this chapter as he looked through a stack of postcards. When he reached this first card he put his finger in the space between the two foregrounded trees, and said: “it’s almost a target, like you can tell the Casino will be there. Even before it was. They knew.” He implied that our eye was drawn to the location even before the site was created. This card was across the bay of Jounieh, below Harissa, and the location beyond the trees would become the famed Casino du Liban.

This third flip-book emerges on the face of new mobilities and the age of mass tourism. After Lebanese independence, and from the 1950’s onwards, the tourism industry greatly expanded. There would soon be a large casino and an expansion of beach culture. Given the discussion of the landscape in the previous flipbook, it remains doubly important to consider these interconnections across time and spaces because they illustrate relationships “on the ground they share” (Corner 1996).

An architect described his frustration in 1951 as such: “the lack of good hotels and beach resorts in a place like Junieh is no credit to Lebanon. In fact it is a cause of wonder and surprise that this place be kept so undeveloped” (Ziyadeh: 2). He continues: “this bay is well known to Lebanese citizens, and to the majority of our neighbours, Syrians, Palestinians, etc.” Yet the paradox he voiced was something not specific to Jounieh as his sentiment echoed through out this time period as many seaside enclaves and mountain villages felt that they each deserved more attention, development, and visitors. Ziyadeh stated: “a country like Lebanon, which claims to be in the first place a touristic country, a place like Junieh deserves a hotel” (ibid: 1).

Many plans were developing in Beirut and within a decade huge projects were realized. Ziyadeh noted the problem of passage at Dog River, the bridge which had graced so many postcards and was extolled by the French as engineering prowess, was now a bottleneck. Many investors were waiting for the “new straight-cut 20 meters highway between Beirut and Junieh to replace the existing narrow and meandering road” (ibid:2). This would cut under the inscriptions at Dog River.

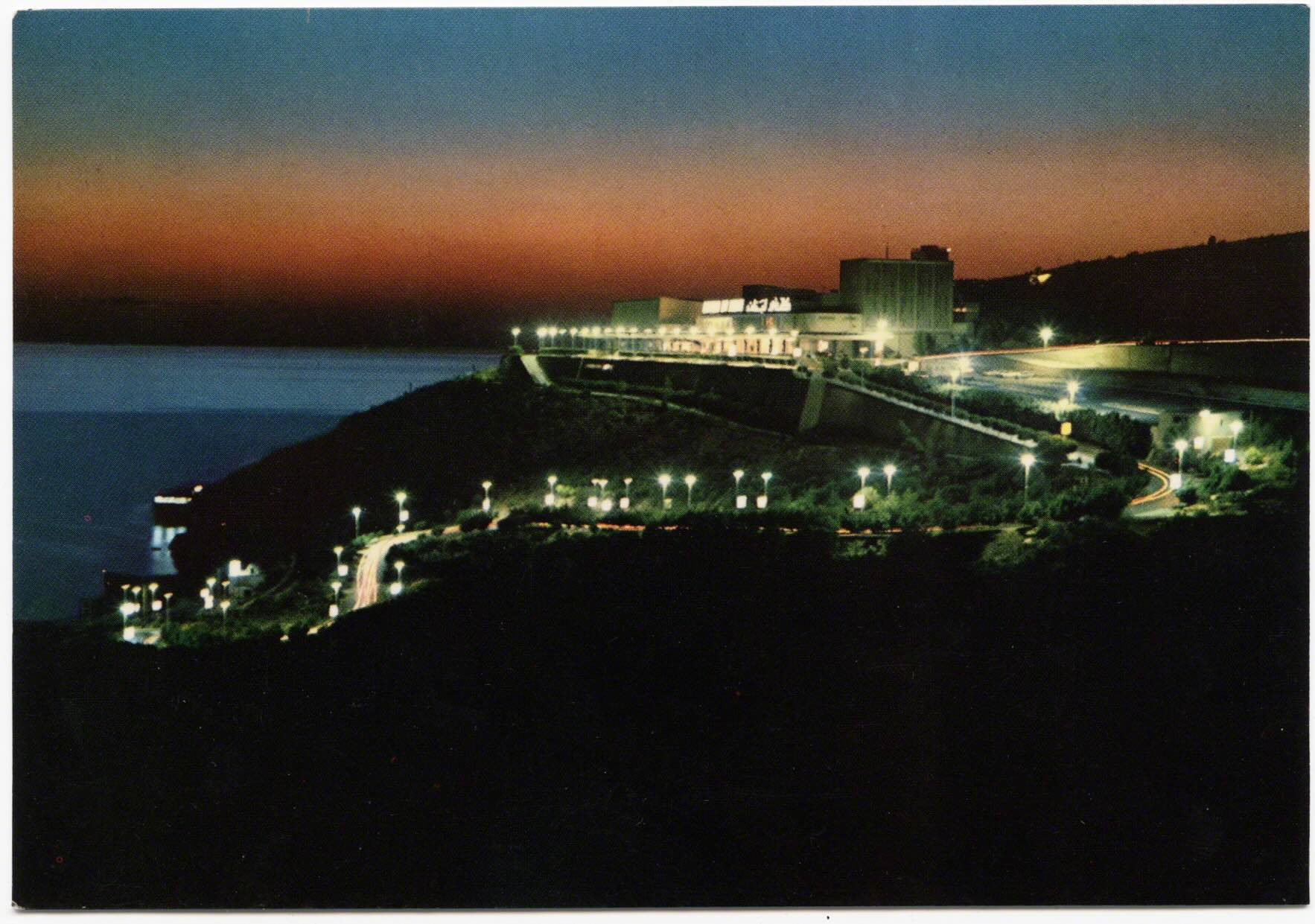

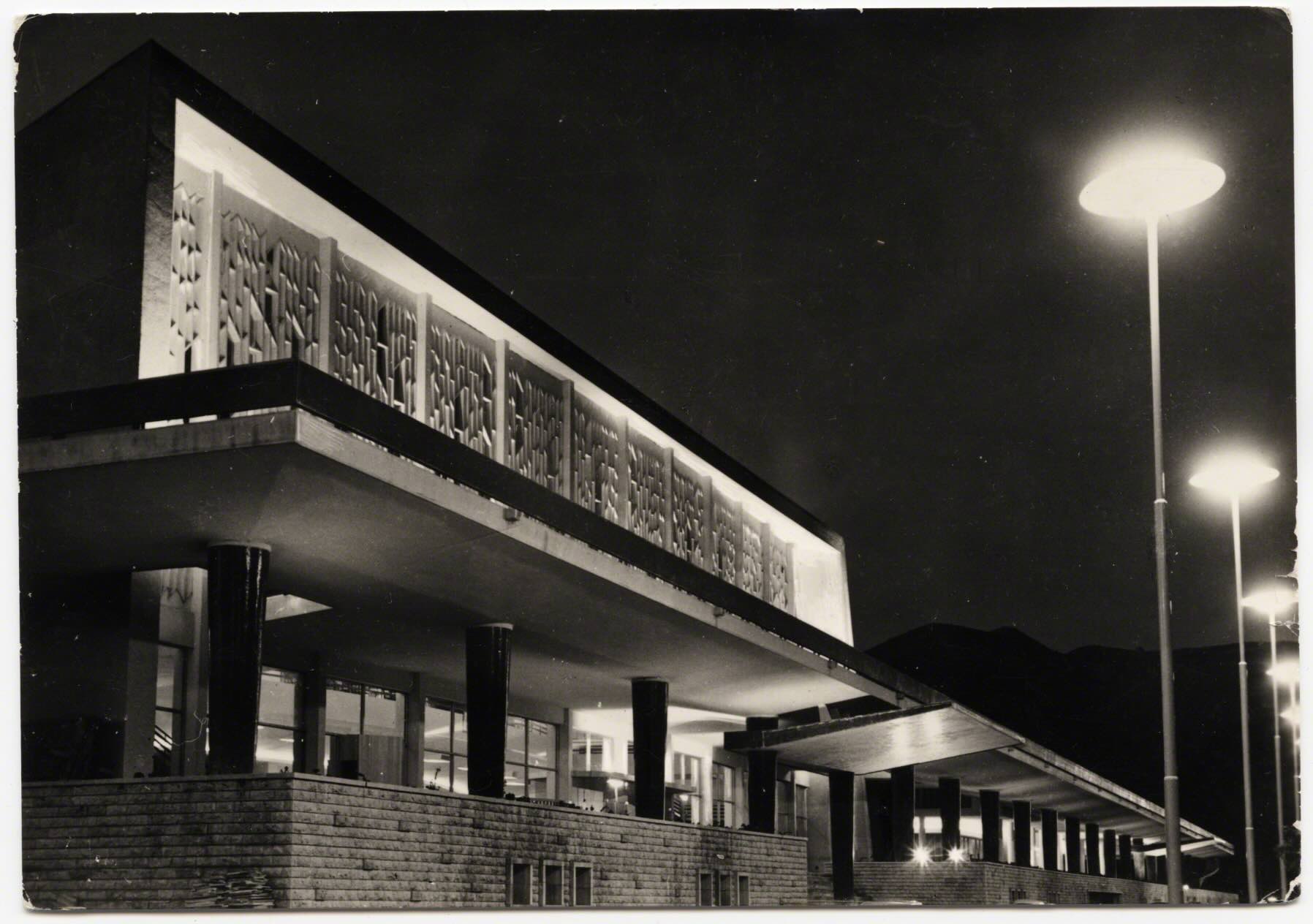

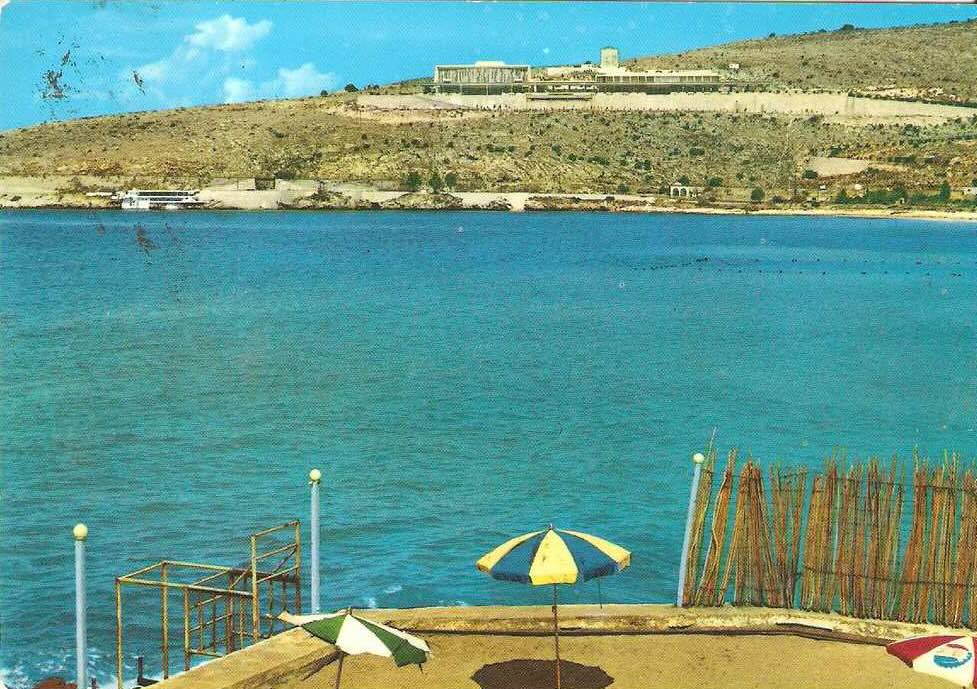

The highway, incidentally, was completed before the casino. The plans for the Casino du Liban were from the early 1950’s and Lebanese president Camille Chamoun wanted to consolidate gambling as well as make a center for tourism. The government issued a decree that allowed official gaming for the Casino Du Liban which opened in 1959. The Casino noted that "Lebanese law (inspired from the French constitution)” selected a non-urban location that was along the coast, “amid 100% natural, untouched beauty." (Casino du Liban 2014:16).

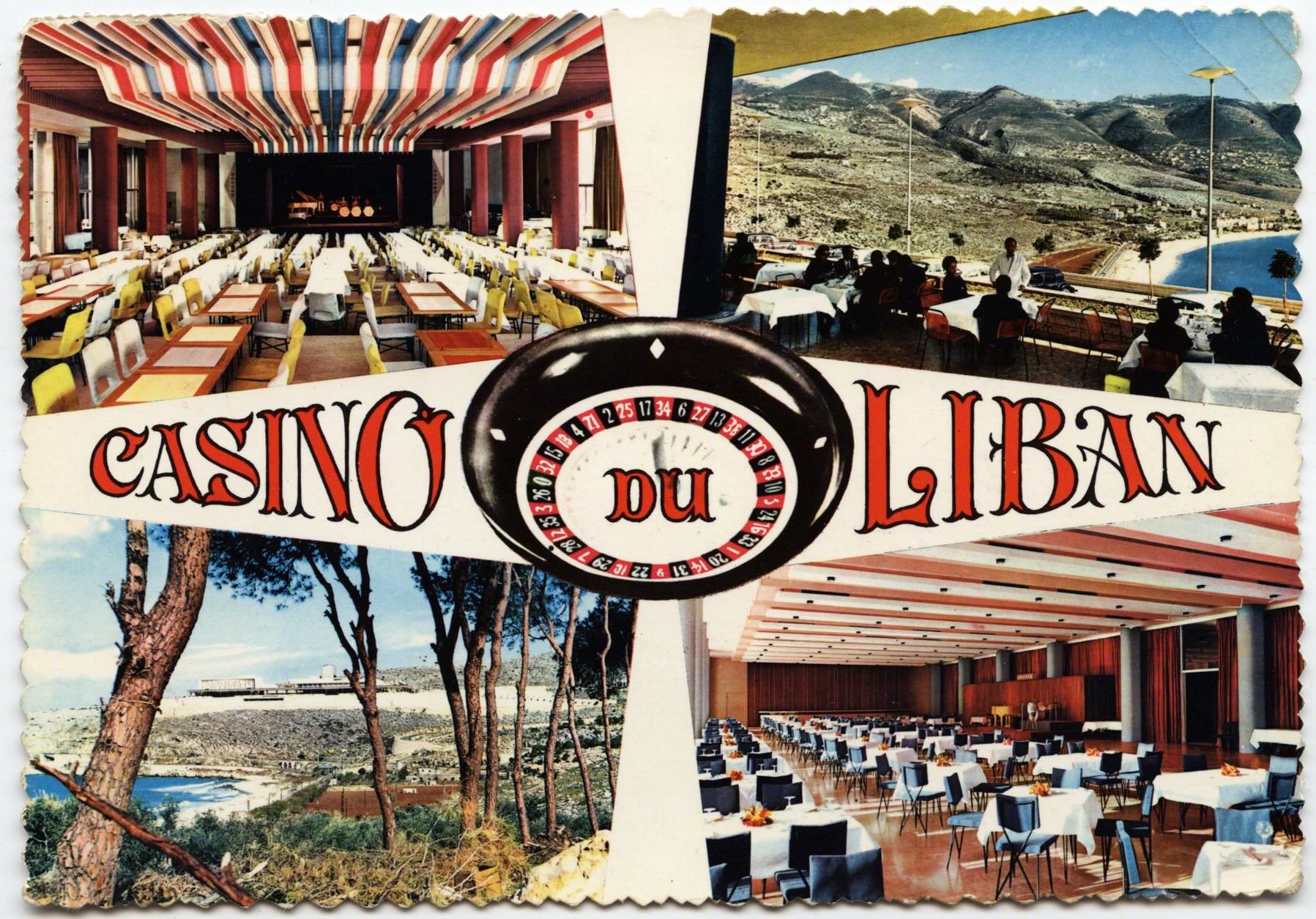

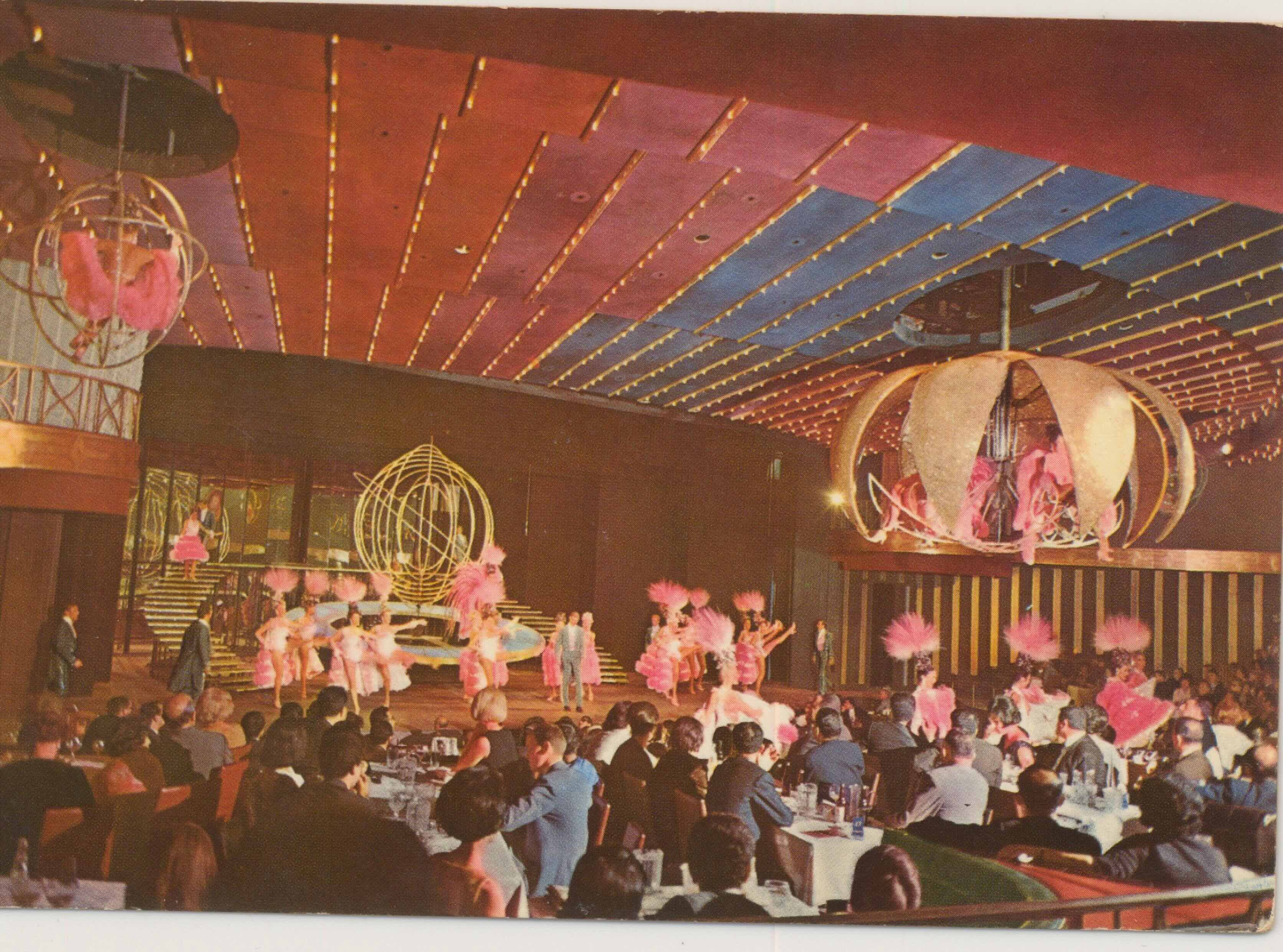

In the publicity around the tourism industry, journalism, and travel logs, the Casino became very well known. More than just gambling it contained an “ultra-modern” theater for 1200 and two restaurants for 2000 people (NAS 1970). The former director of the Casino Victor Mussa said of this time period in the 60’s that “the reputation of [this] small country began to grow and exceed its boarders” (Skaff 1996: 2). Like the mountains becoming a global trope of eras prior, now the Casino (and beach) would become symbols of the nation. The reputation spilled over the boarder and postcards were one means that delivered this message. Clientele flooded the casino as the types of shows, beauty pageants, and concerts increased. In terms of volume in the 60’s, it exceeded that of Monte Carlo and Cannes (Sifakis 1990: 184).

A self-described American hotelier said of the Casino du Liban that it was as “sophisticated” and “rivaled” Las Vegas but with clientele “drawn from the top drawer of Europe and Arabia.” (Venison 2005: 249-250). Another visitor noted that the luxury of this site “mirrored the men who used it" and that the only limitation was “the acres it occupied.” (Atkinson 1973: 63). The Encyclopedia of Gambling from 1990 noted, during this Golden Age of tourism in Lebanon, that the Casino du Liban was the “best, most lavish gambling center” of the entire Middle East and the “crown jewel” of the area during these decades (Sifakis: 184).

As the years passed there were more metaphors used to illustrate the scope and scale of the casino, as well as to frame the broader tourism industry. As nauseating as many of the clichés become, they were powerful ways of imagining relationships. The bay of Jounieh had become the “Monte Carlo of the Middle East” and the “20th century version of the exotic orient” (Takla 1966: 16). The Casino du Liban was said to be the “Las Vegas-in-the-Levant, the biggest and most pretentious thing of its kind anywhere on the Mediterranean shores, not even excepting, in my view, the Casino of Monte Carlo (Clark 1963: 415). And the Eastern Trade Directory called it "one of the most important distraction centers of the world" (Eastern Trade Directory 1968 :119).

If distraction implies diverting one’s focus, then the surface of these cards, as well as the reality of the casino, served as a space of not just distraction, but extraction. The shows of the Casino werefamed. Women were lowered in circular pods which opened, like flowers and elephants marched through the audience (Ellis 1970:251) The casino had the “most striking floor show I have seen anywhere in the world and a huge cast of beautifully dress (or undressed) girls” (Koenigil 1968: 94-95). An airline periodical, showed an image of a dolphin’s head poking out of a wooden crate at the Beirut airport, noted "after entertaining the customers at Beirut's stupendous Casino Du Liban, dolphins are tenderly transported by TMA (Trans Mediterranean Airways) to London." (Esso Air World 1970: 62). So, in addition to the influx of visitors Dolphins were now flown to Beirut for the weekend weekend performances.

Besides animals and flesh, there were endless stories of scandal, spies and sex that emerge from the Casino du Liban. It was in numerous films which always focused on espionage and danger just as Lebanon was imaged (and in practice though residual colonial and imperial interests) a juncture between East and West. Others stood by their comparison to the brand of films, noting it was a “real backdrop to a James Bond novel” (Venison 2005: 250).

In what ways does visual imagery fold back into the growing narrative of the Lebanese tourism industry as excessive, permissive, extravagant, and luxurious? Tilley notes in the work of De Certeau (1984) the spatial practice of stories and narratives and here the postcards function as a “discursive articulation of a spatializing practice” (Tilley 1994: XX). While the casino was on Lebanese soil, like other parts of my work (namely on Hotels in Beirut and Summering villages in the mountains), these spaces were predominantly for foreigners and rich Lebanese – the casino “lured the jet-setters, Greek shipping tycoons, oil sheiks (Sifakis 1990: 184). It was “a marble and glass palace…East meets West once more as tall blonde Scandinavian chorines stage performances that rival those of the Lido while Arabs play baccarat and American oilfield workers shoot craps.” (Smith 1965).

It was this increasing contrast of nationalities, wealth, and seeming discrepancies of what produced much excitement. These narratives of the Casino were mirrored in the air that filled the tourism balloon: half hype + half hope. Year after year getting bigger, and despite being blown around in the winds of conflict in the 50/60’s, the balloon kept sailing higher, bigger. Did it float too high loosing sight of the ground, of the citizens and landscape from where it came? A recent memoir from two Lebanese brothers noted that Lebanese could sometime have problems accessing the Casino. At some point, in their experiences, Lebanese were prohibited "from entering the gambling rooms, but if you owned a few properties and were approved by the Treasury Department, then no problem." (Mechawar & Mechawar 2013: 254). This similar exclusionary spatializing practice would be one that emerged with full force in the tourism industry, which hints to how, and under what circumstances, people were privileged, invited or welcomed.

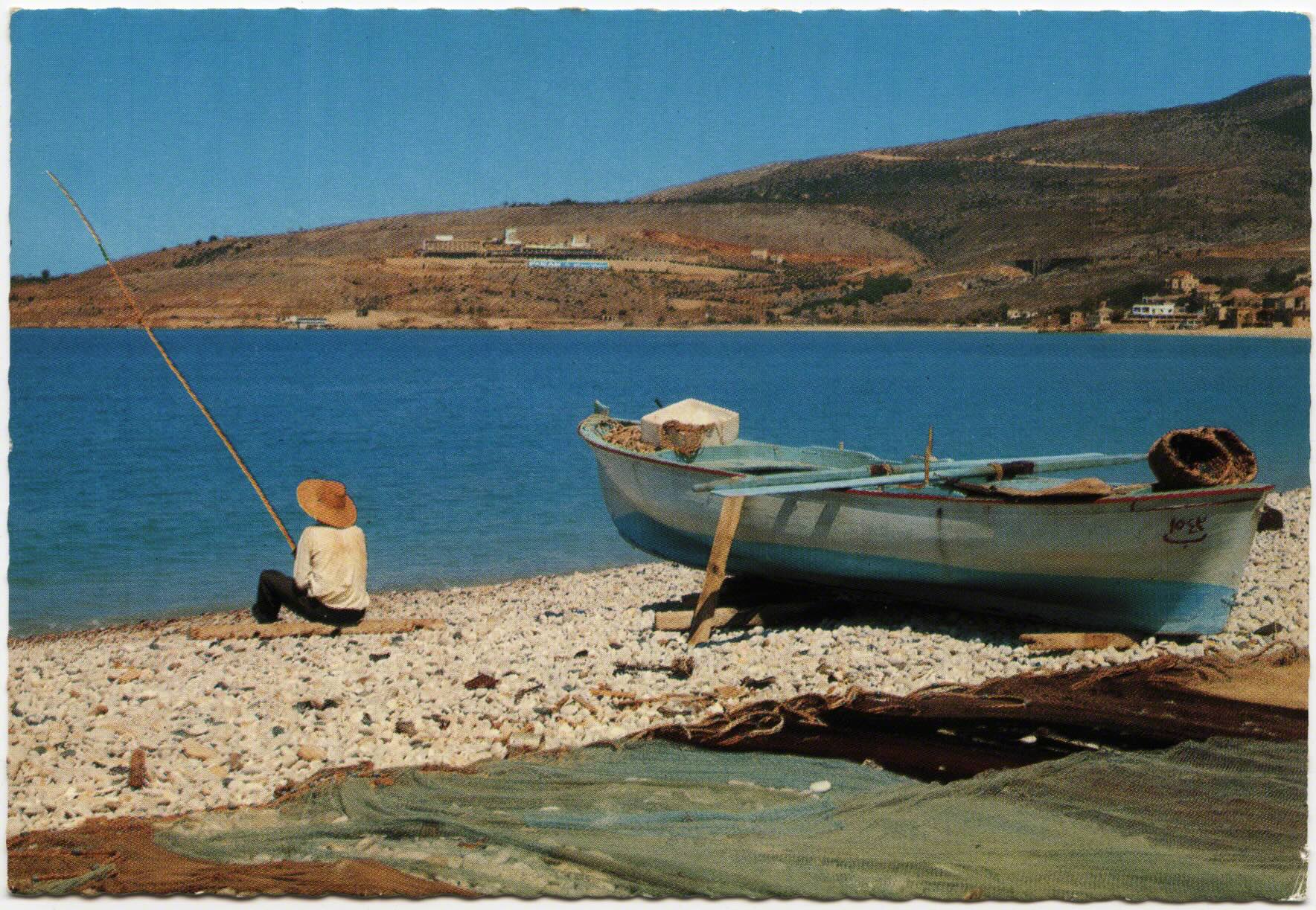

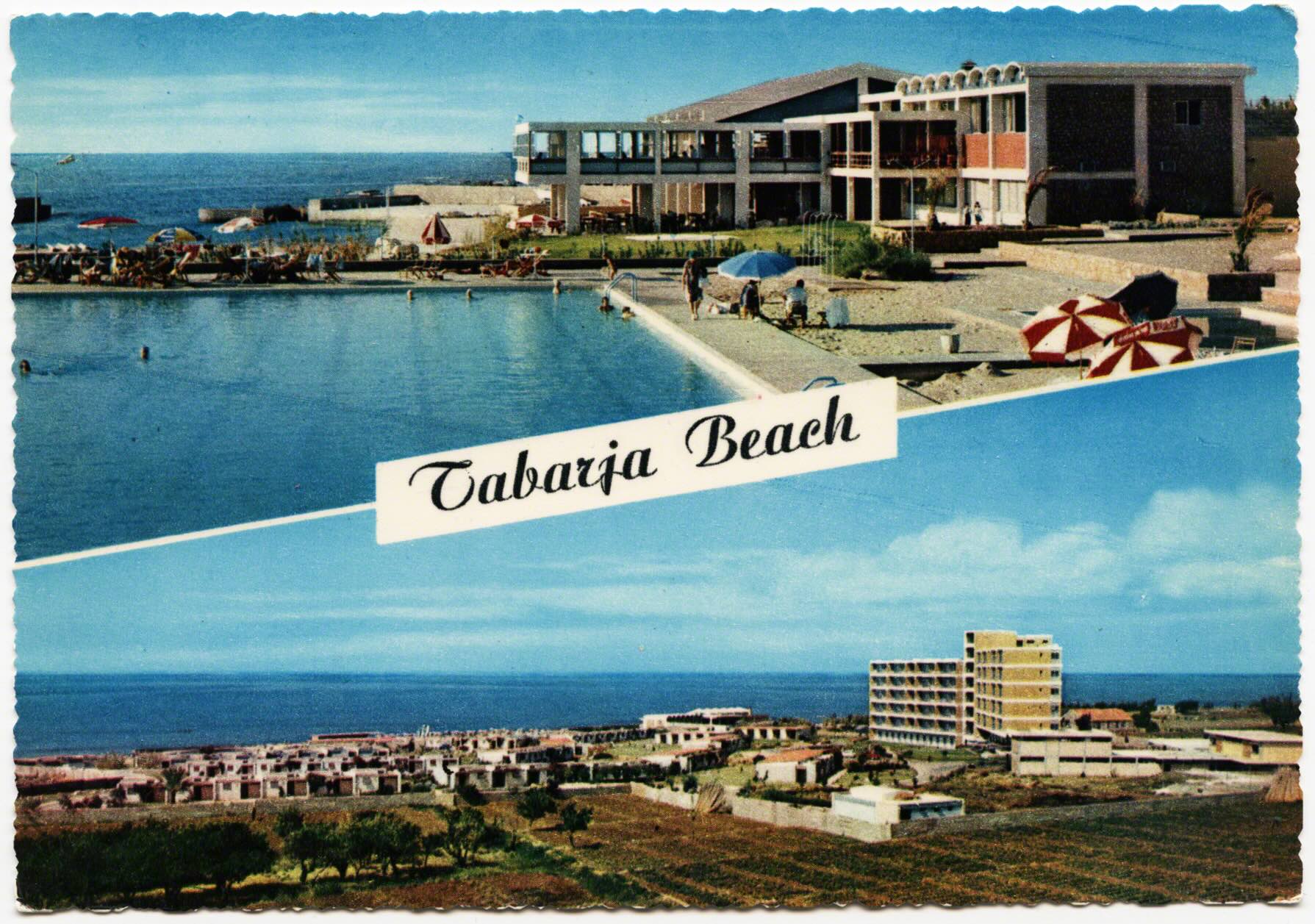

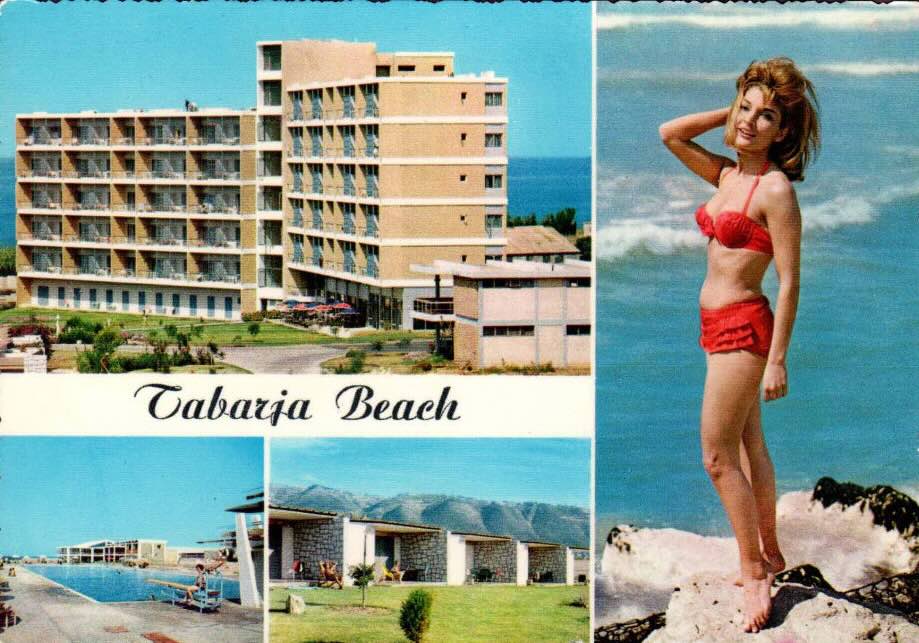

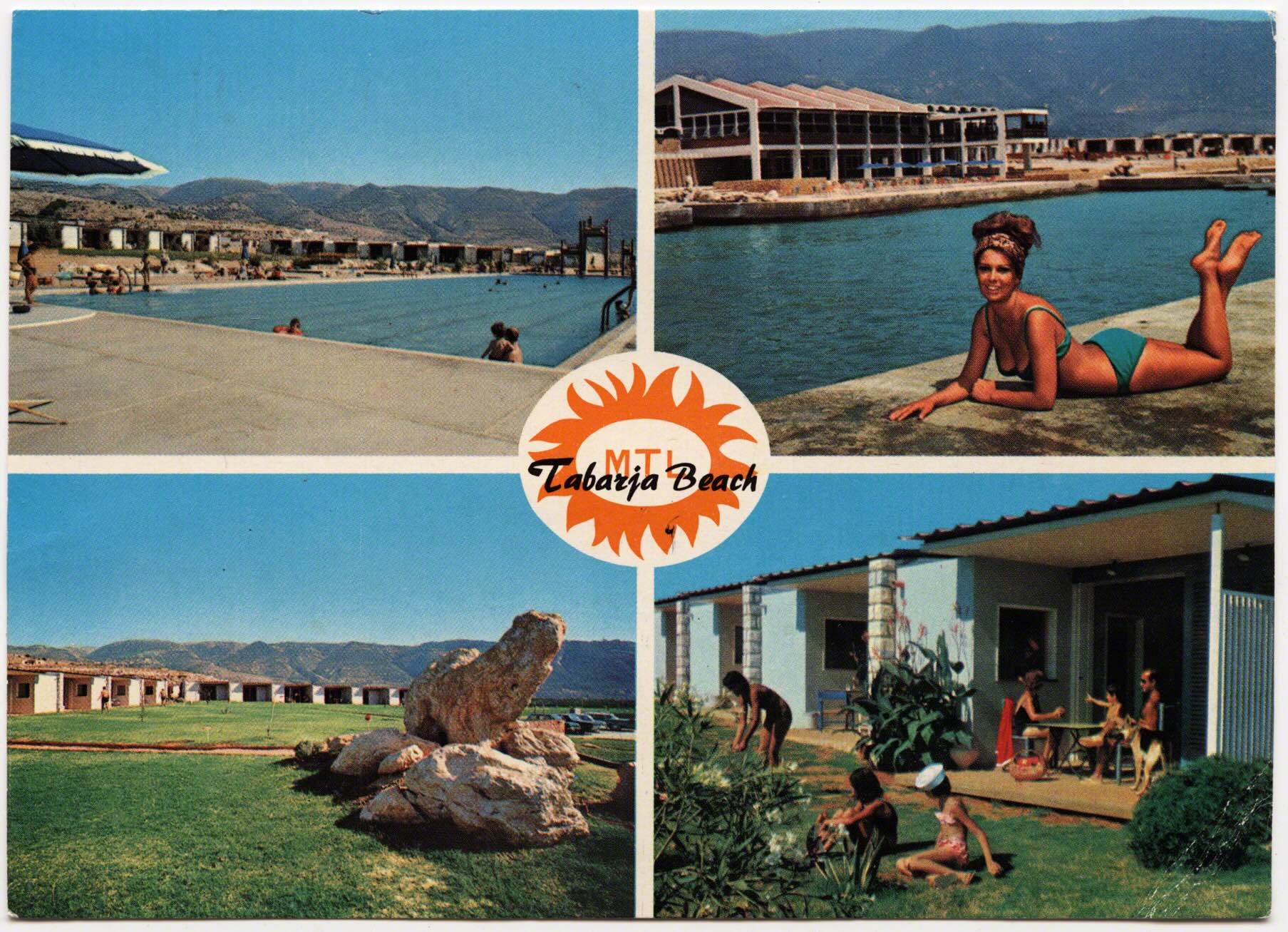

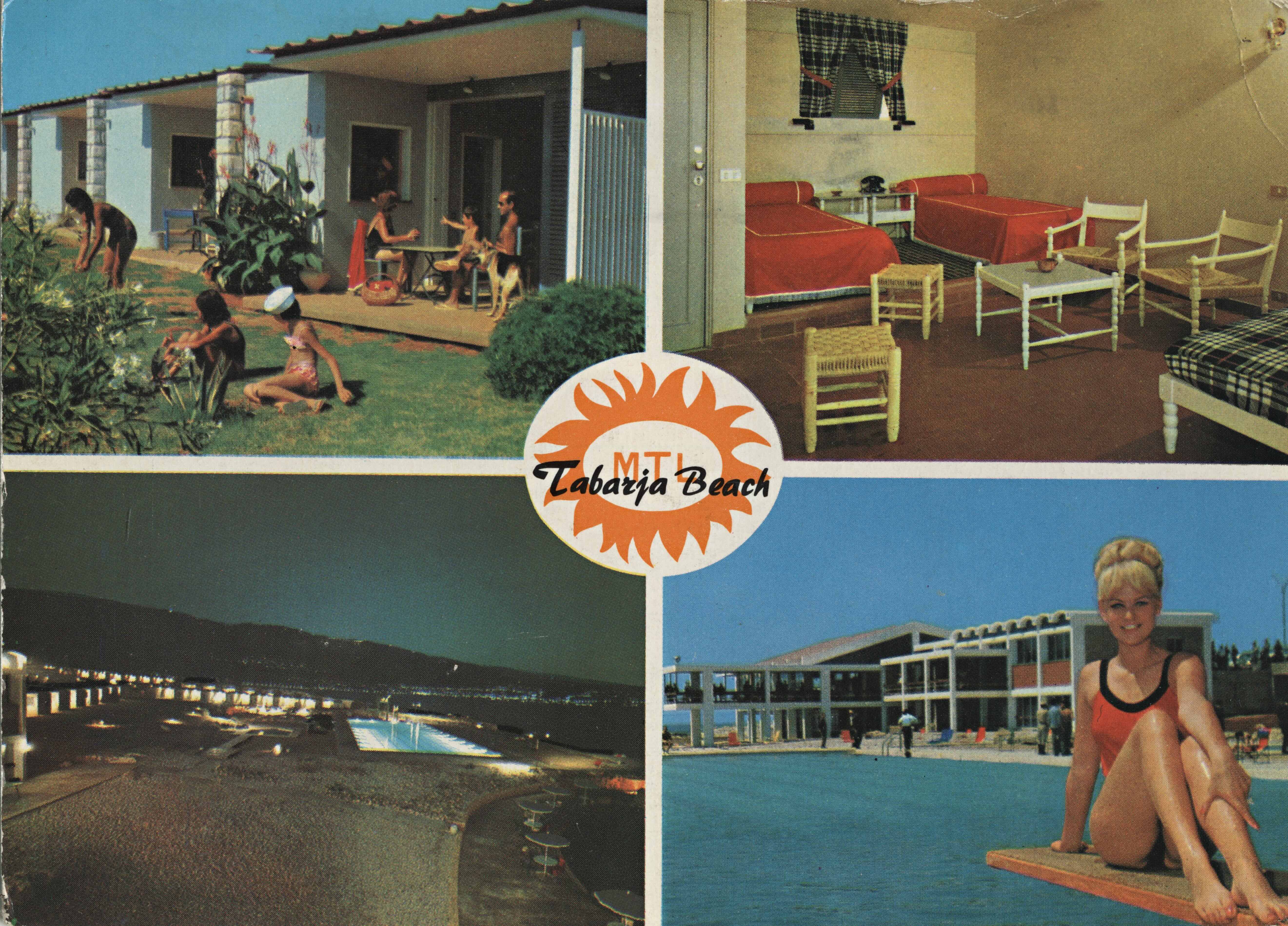

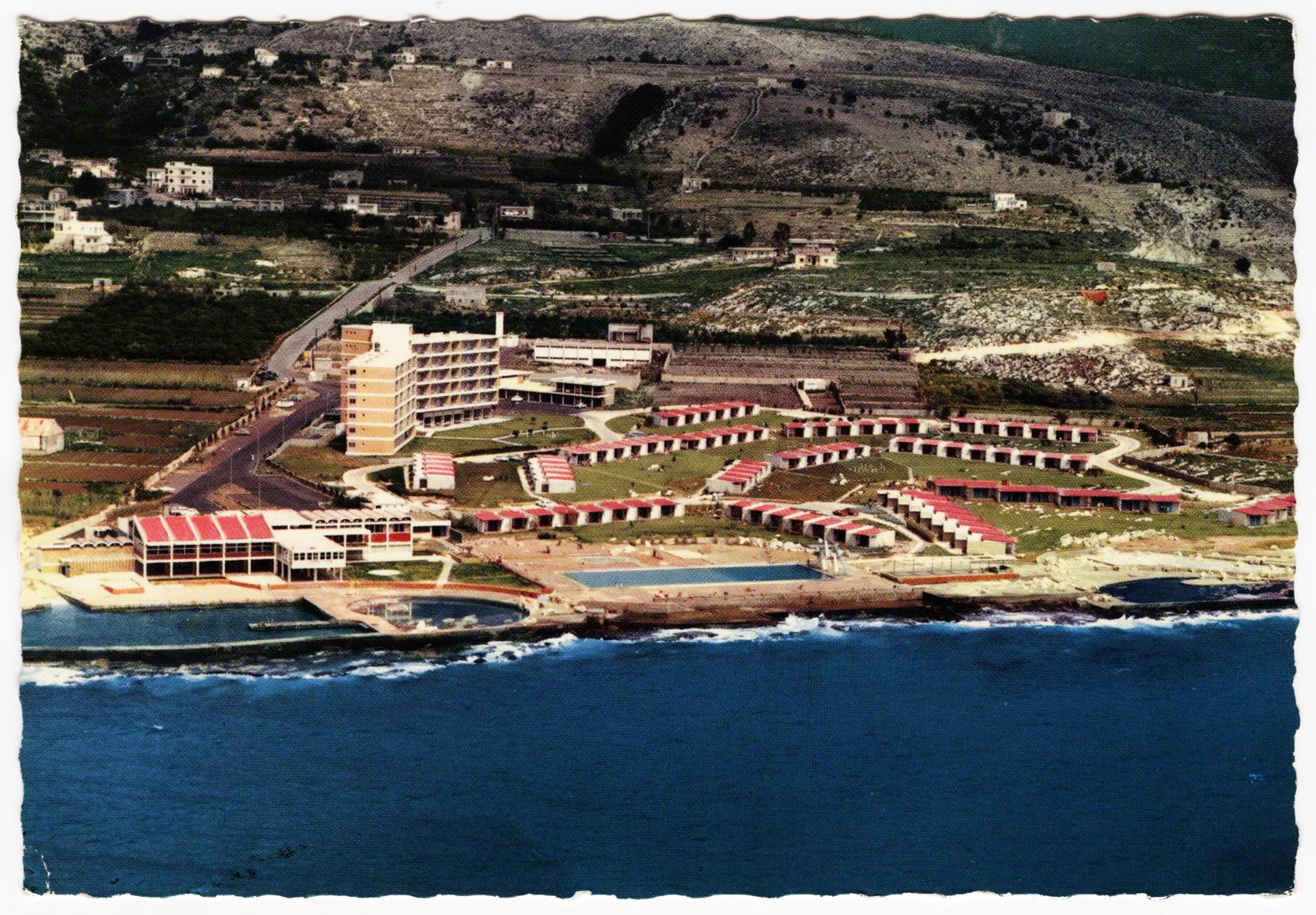

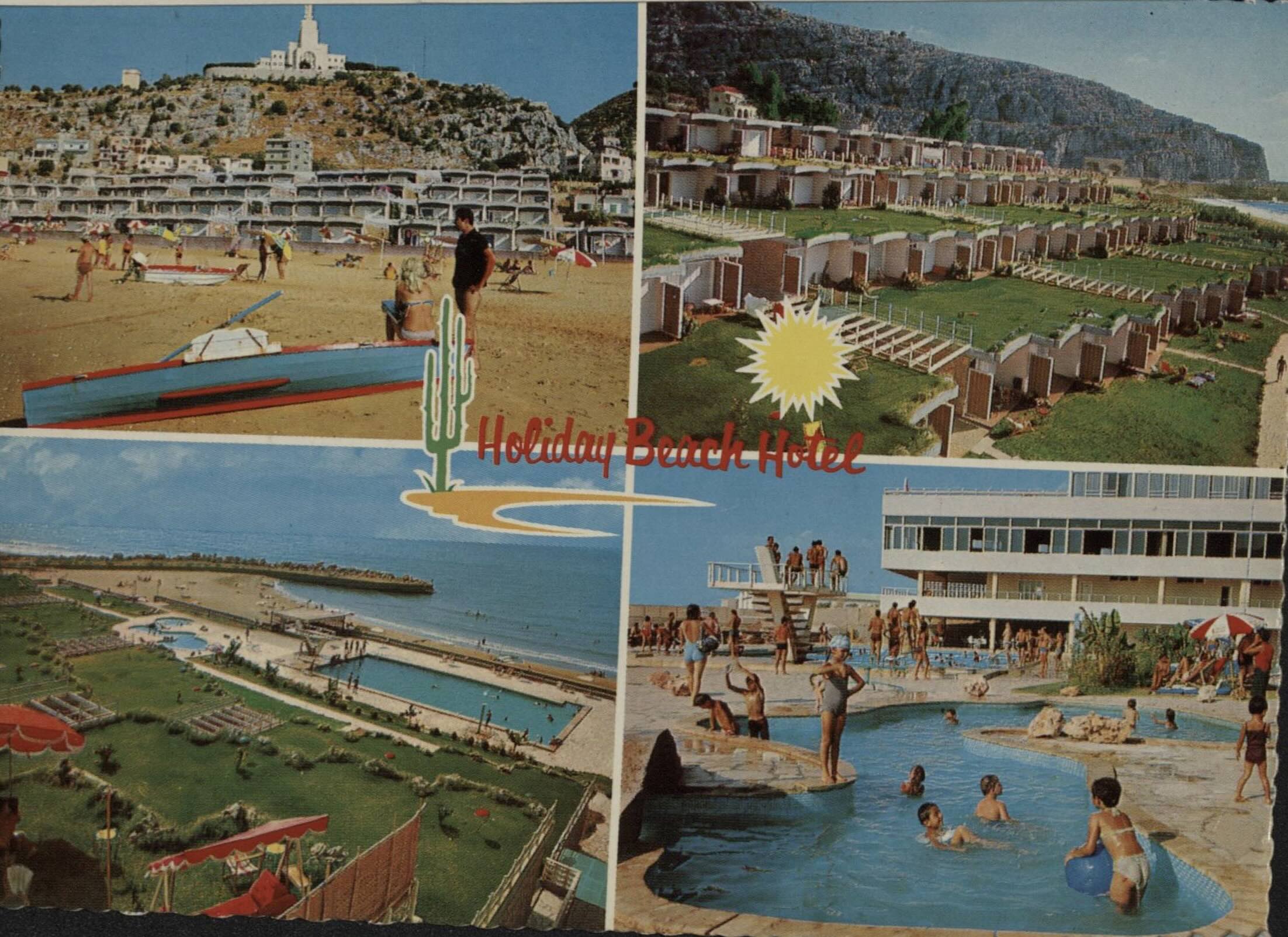

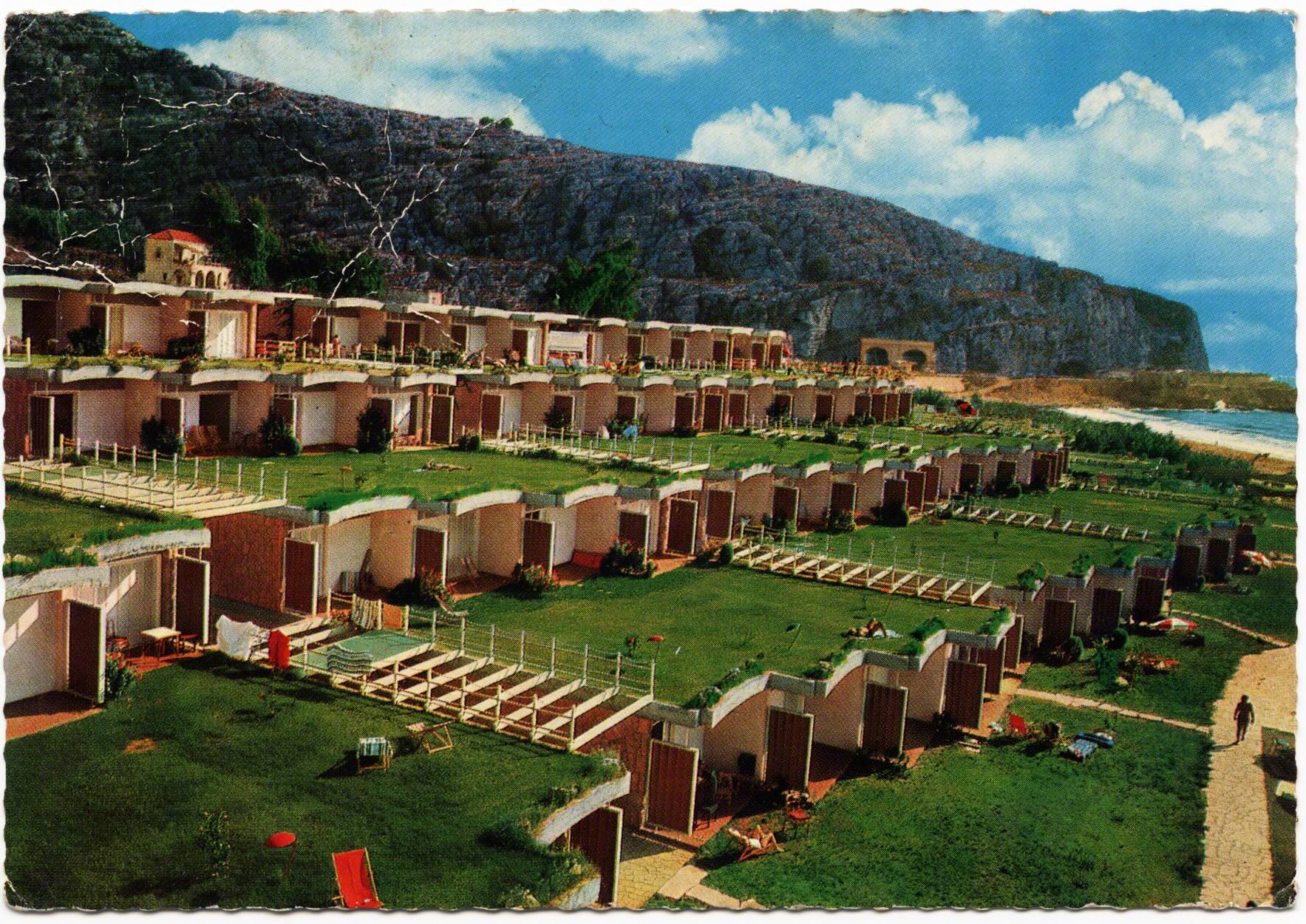

At this same time the casino developed, so did the coastline. Below the casino as the bay curves there was a small village named Tabarja, where St. Paul was said to have set sail to Europe (Rowbotham 2010). By the early 1950s many beach resorts were opening across Lebanon, which expanded conceptions of the summertime and a large beach resort opened called Tabarja Beach.

Americans and Europeans were one target in expanding tourism in the 1960’s as Gulf Arabs continued to stay in the mountains in the summer. “Among developments designed largely for the American trade is the new Tabarja Beach Hotel north of Beirut, building facilities for 400 guests with an Olympic-sized pool and a yacht basin” (Kanner 1965: 149). One travel periodical from NewYork described it as a “new luxurious resort near Beirut…bungalows with private gardens, music, refrigerators, may be hired by the day for $14.00 each." (Travel 1964: 15). Kim Philly even picnicked, and drank, here before leaving Lebanon (Seale & McConville 1978: 303).

By the mid 1960s Jounieh has a strongreputation as a “summer” spot in the spine of Lebanon’s coastal developments. Saudi Aramco promoted it as the “most lustrous jewel in the chain of coastal resorts that have won Lebanon the apt title, ‘Riviera of the Middle East’” and “jewel of Lebanon” (Tracy 1968: 22?) . The PanAm Guide for American’s Living Abroad noted that one could rent a summer beach chalet for $490-$1,145 at Tabarja Beach (Pierce 1965: 263). These spatializing practices, realized through the market, already show a preference for foreigners and only those Lebanese that had enough money to afford access.

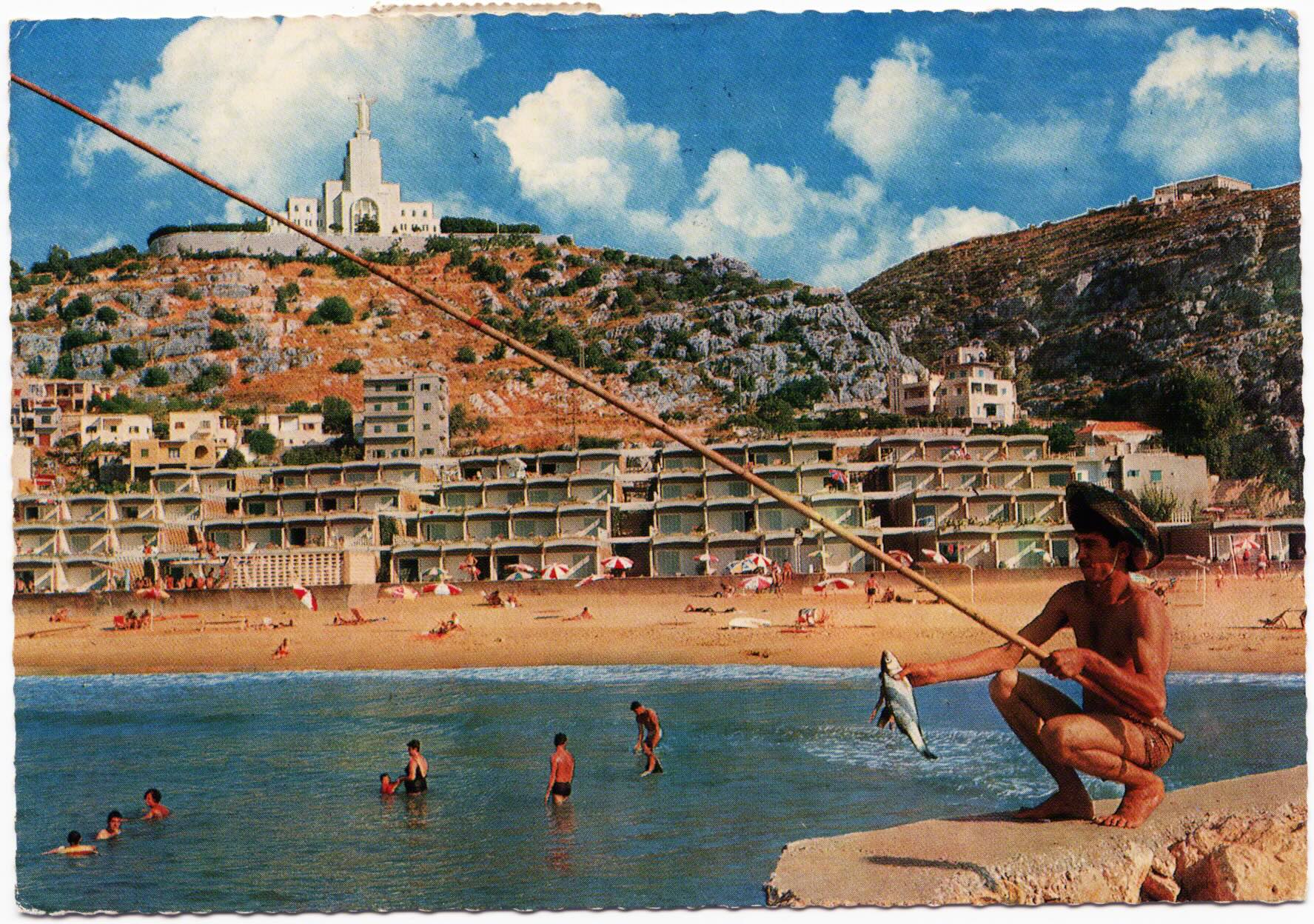

As in the previous flip book, we returned back to Dog River for a twin development. There was a beach lesiure project that mirrored Tabarja Beach, on the Northern side of the river, below Jesus the King. When Holiday Beach was established it was not as luxurious as Tabarja, but it became well known. These postcards show a view that one might see swiming in the mouth of Dog River, under the gaze and embrace of the marble effigy.

By this point the medium of postcards were meant to condense in order to project a certain perspective. A “snapshot” of meaning - capsule - glance - moment - hope - desire. During this era postcards were more directly linked to the establishment, and bolstering, of the tourism economy. Often these cards were produced by the entrepreneurs and actors who would directly profit off of their circulation (such as hotels).

In this way, the “surface” of these images is glossier, shinier. This sheen doesn’t hope to capture an essence as previous decades’ postcards might have, but hopes to foster and cultivate one. The reflective power in these postcards frame an aspirational future, and I posit, one that is more fun, extravagant, and sensual. In this age of mass tourism so too does imagery become mass produced and consumed. The tourism industry becomes more linked to visuality, the camera, and changing public relations driven by investments and profits.

While the discussion of postcards began by thinking how they can stand as a metonym for travel and mobility, by this point in Lebanon they represent a “metonymic fallacy” for the nation (see Barthes 1975: 161-162). The tourism industry, and what it represented, I would argue, was often taken to be the referent and stand-in for the nation. As if these surfaces were representative of Lebanon, when these flipbooks are eddies of tourism. Traps not paths. This fallacy was enhanced by visuals, photography, postcards, stamps (etc.). Many of the postcards also used techniques to encase and envelop the viewer in an eidetic frame of reality. Through the coloring of the photographic negative (like an Instagram filter), the framing of the waves, the smile, or how they draw the viewer into them. The genre of montage becomes popular, which is only telling in so far as the types of views that become assembled on the card indicate an eddy in which one’s body and view is stuck.

In this time of increasing masses: mass-tourism, mass-mobility, mass-consumption, mass-imagery, we are reminded of Kracauer’s ornament (1929). He noted that the masses produce a form and structure through these ornaments which reveal "the aesthetic reflex of the rationality to which the prevailing economic system aspires.” Postcards were aspirational but these surfaces reproduced values of the capitalism production in which tourism was trapped. Tourism was folded into public relations and became a main artery of the national economy.

Guy Debord building on Kracauer’s work proposed “spectacles” as a modern version of the ornament (1987). Debord explores the relationship between visual culture and commercial interests where "spectacle obliterates the boundaries between self and world...here surface exceeds its frame and consumes the world around it” (Debord 1987: 221). Thus, the mass spectacle of tourism, and postcards, interpolated the Lebanese, as well as the world. As such, these postcards are little more than caricatures of place which resembled it in likeness, a simulacrum, but were actually an “extravaganza of undifferentiated surfaces” (Baudrillard 1989: 125). As such, they are surfaces of surfaces.